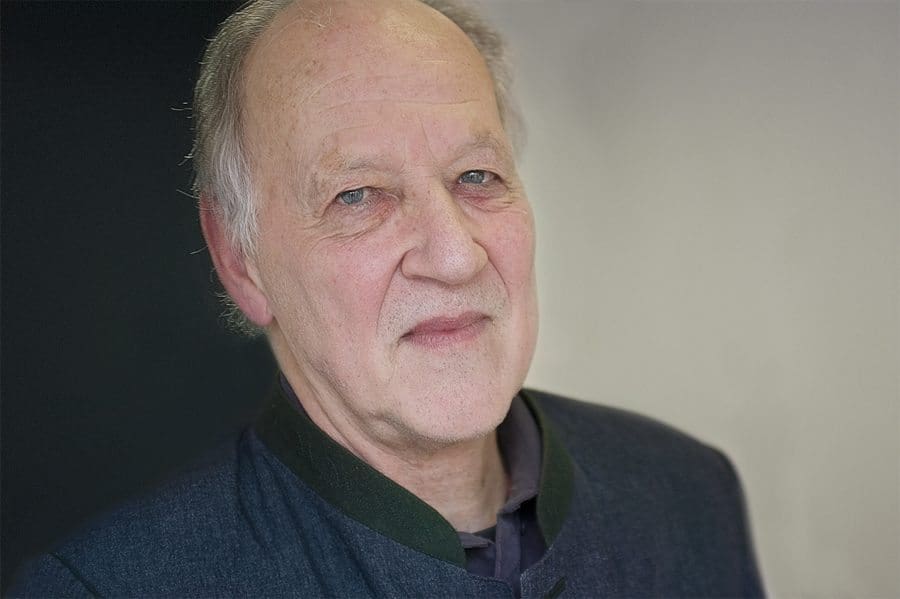

Werner Herzog

has often gone to extremes, from Amazonia to Antarctica, in search of truth. The German auteur’s documentary Into the Abyss had lately taken him to Death Row when Huw Spanner encountered him, just off Notting Hill, on 27 March 2012.

Photography: Andrew Firth

You have said that ‘Into the Abyss’ would have made an apt title for quite a few of your films, from Aguirre, the Wrath of God1His 1972 film starring Klaus Kinski as the Spanish conquistador Lope de Aguirre, who leads his men to their eventual destruction in a futile search for the city of El Dorado even to Cave of Forgotten Dreams.2His 2010 documentary, shot in 3D, about the prehistoric paintings in the Chauvet caves in southern France It reminded me of a line in Woyzeck: ‘Every man is an abyss. You can get dizzy looking in.’3Jeder Mensch ist ein Abgrund; es schwindelt einem, wenn man hinabsieht. Was that what you were alluding to?

No – however, it’s not far-fetched. One of the producers wanted to call the film ‘The Red Camaro’, but I felt that we are not car salespersons and I said: No, it has to do with looking deep into the recesses of the human soul. It’s like gazing into an abyss.

When I first heard that title, it put me in mind of a verse from the Bible: ‘The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked: who can know it?’4Jeremiah 17:9 (KJV)

That is what my profession is about: you have to know the heart of men to do a film like this – or to be good at directing actors.

It’s a fascinating quote from the Bible, because why is there wickedness? Why does the Creator create this kind of people? Pope Benedict, who I like as a person of deep philosophical insight – I think he’s the deepest-ploughing thinker in the Papal See for centuries – in his speech in Auschwitz repeatedly asked: Why did God allow such a thing? Where was God then? It’s really a bold thing for a pope to ask.

I seem to be one of the very, very few thinking people who defends [Pope Benedict].

You don’t believe in God, do you? Or do you?

No. Well, I had an intense religious phase when I was 14 or 15. I became a Catholic – and, by the way, according to the dogma of the Catholic church you cannot leave: you are always baptised, because baptism is an indelible mark on your soul. But, from my side, I am not a member of the church and I am not religious.

Watching Into the Abyss5Into the Abyss: A tale of death, a tale of life, released in British cinemas in March 2012 and on DVD a fortnight later and then a number of your other films, I got the impression that you are very concerned with the unknowability of the human heart, and our mutual incomprehension –

Yes.

I grew up in a world where there were no fathers around – either they had perished in the war or they were prisoners. There was anarchy in the best sense of the word

– but not, in fact, with our wickedness and deceit, even though the murders that are the subject of Into the Abyss are truly horrific, and the two men convicted for them insist, unconvincingly, that they didn’t do them. You’re looking into the abyss and it’s unfathomable, maybe, but there is no sense that it is dark particularly.

Well, the abyss is not really dark. The crime, which is in a way the leading character in the story of the film, is absolutely senseless and it’s the nihilism of it that is so staggering and so disturbing. You are not looking into darkness, you are looking into an empty void.

I believe that Michael Perry, who was executed eight days after I filmed with him, was probably the most dangerous person I’ve met in my life.

He is quite engaging in the interview, isn’t he?

He looks like a lost kid. His co-defendant, Jason Burkett, who is big and intimidating and can look really angry, was not as scary as him.

Can you say exactly why you wore a suit to interview Perry – and also the men in your three-part TV series Death Row?6Screened on Channel 4 on 22 & 29 March and 5 April 2012

I didn’t wear it for any formal reasons – I’m always invisible, behind the camera. No, it was out of respect for a person who is going to die soon. My basic attitude was always that the crimes are monstrous but the perpetrators are not monsters, they are always human, and I respect them as human beings.

Would you have worn a suit to interview even a man like Jean-Bédel Bokassa7The self-styled emperor of the Central African Republic, who was the subject of Herzog’s 1990 documentary Echoes from a Sombre Empire. Herzog has asserted that he was a cannibal and ‘seemed to represent the kind of human darkness you find in Nero or Caligula, Hitler or Saddam Hussein’ (Herzog on Herzog). He had permission to interview Bokassa in prison, but was expelled from the CAR before he could. Bokassa was later released and eventually pardoned. when he was awaiting execution? Or even Adolf Eichmann?8One of the principal architects of the Holocaust, who was tried in Jerusalem in 1961 and hanged the following year

Yes. In all cases, without exception.

I would not be an advocate of executing anyone. For me, it is a question of categorical principle: that a state under no circumstances, for no reasons whatsoever, should have the capacity to kill anyone. Except in warfare – I’m not 100-per-cent pacifist.

Pope John Paul II spoke of a ‘culture of death’, meaning genocide as we had it in Germany, capital punishment, assisted suicide, abortion – it is not the meaning of creation, as he understood it, that abortion should be an everyday event. And I find this argument very compelling, even though I do understand that women should have [a choice].

You’ve said elsewhere that for you the case against the death penalty is not an argument but a story: the story of Nazi barbarism. How did the war and its aftermath shape you, your character and your imagination?

The war itself was absent in my childhood, and I didn’t grow up [amidst] ruins. There was no fighting where my mother fled, in the Tyrolean mountains – not a single shot was fired, there was no bombing, nothing.

But the war shaped me in a way, in that I grew up in a world where there were no fathers around – either they had perished in the war or they were prisoners. There was (and I say it with a necessary caution) anarchy in the best sense of the word. There were no fathers, no clear rules. We had to create our own rules.

And, may I add, we had no running water, for example. You had to fetch water in a bucket from the well – which is a wonderful way to learn the value of water.

Going back to the red Camaro, it is our shallow consumer culture that has helped to prompt young men to commit murder just to get a desirable car, isn’t it?

Well, it’s a very interesting idea. Yes, you’re right.

Well, it’s a very interesting idea. Yes, you’re right.

Whereas you have said in the past that, in spite of the extreme poverty, you had a wonderful childhood. Do you feel sorry for children growing up today in the West?

Not sorry, but… My own three children never participated in affluence. They never threw food away. It is just unthinkable for me, because I was very hungry as a child. It pains me to see people in restaurants, in Germany or the United States, throwing food away.

You’ve often talked about the beauty and the horror of the universe. It’s hard sometimes, because you have such a mischievous sense of humour, to tell whether you mean it or whether you are being provocative.

But when you look at it, there is no harmony in the universe. It’s very hostile, very disordered, very chaotic – it’s unpleasant even thinking of venturing out there. If you expect something benign, orderly, in full harmony, it’s just not the way the world is created.

Do you find that human beings are of a piece with the rest of creation? Are we also beautiful and horrifying?

Of course we are part of this creation and of course we are, in a way, ill conceived, like the rest of what we see.

And yet it would be easy to name other writers and directors whose work is full of human nastiness but, apart from the two pimps in Stroszek [1977], it’s hard to think of any really wicked people in your films.

Yeah, that may be right. Of course, in Into the Abyss I say explicitly to Michael Perry, ‘Your childhood was complicated, but it does not exonerate you and it does not mean that I have to like you.’ And that’s unusual, because normally I like the protagonists in my films – they are always people who are close to my heart.

Many people have commented that your feature films and your documentaries alike are often about marginal or eccentric people, or ‘freaks’ and ‘monsters’ –

Well, that’s the commentators’ problem.

But you have said – and I don’t know whether you were just being provocative – that, on the contrary, you see all these people, even Aguirre, as normal and it’s the people around them that are –

Bizarre. And mavericks and…

But in Into the Abyss you treat everybody with respect, and in a way the most impressive people in the film are the chaplain, the policeman and the former executioner, who all represent ‘normal’ society.

Yes, but, you see, Into the Abyss in a way is an exception to how I normally would do a film. In a documentary, I would stylise, I would invent, I would bring in elements that are complete poetry or science fiction. Like in Cave of Forgotten Dreams there is a chapter at the end about radioactive mutant albino crocodiles. I want to take the audience with me into a realm of fantasy and poetry and it’s completely wild. But you don’t do that when you are sitting in front of a man who is going to die eight days later. There won’t be any albino crocodiles. So, in a way I think this film is slightly different.

In Herzog on Herzog,9Faber and Faber, 2002 you say that there are things in your documentaries that you made up – there’s a quotation at the beginning of Lessons of Darkness10A ‘documentary’ shot in the burning oilfields of Kuwait in 1992 that you attribute to Pascal, and one at the beginning of Pilgrimage11An 18-minute ‘documentary’ made with John Tavener for the BBC in 2001 you ascribe to Thomas à Kempis –

Yes! Beautiful, beautiful –

I have the joy of storytelling in me. I would invent anything if necessary to help you to rise above your existence into the realm of something sublime, something horrifying, something of great beauty

Yes, but you made them both up.

Because neither Thomas à Kempis nor Pascal could have said it better.

So, you are happy to fake things – and yet in Fitzcarraldo [1982], when you wanted to tell a story about a 340-ton boat being dragged up and over a steep hill in the depths of the Peruvian rainforest, you actually did it.

It’s not a contradiction.

Can you explain?

In a documentary, I would be inventive and I would fantasise in order to reach a deeper stratum of truth. In Fitzcarraldo, I moved a real boat over a real mountain, but it was not for the sake of realism. I’m not interested in realism. I transform a real event into pure fantasy, into something operatic. I like films where audiences can trust their own eyes, but not in a pedantic, bureaucratic way. It’s not the ‘accountant’s truth’; it’s something we’d like to see in a movie – Oh, yes! A real ship and, man, it’s moving over a mountain! – in order to create a gigantic metaphor.

But isn’t the bottom line that if an audience sees a Pascal quotation on the screen, it has to be something Pascal actually said? Doesn’t it destroy people’s trust in you when they discover that you made it up?

Let me quote it. At the beginning of Lessons of Darkness it says: ‘The collapse of the stellar universe will occur – like creation – in grandiose splendour.’ Under it, it says ‘Blaise Pascal’. When the first image arrives on screen, you are already elevated, you are transported into something sublime – and I never let you down from there. And that is the reason, and I would invent anything if necessary –

I still don’t see why you can’t attribute that opening statement to yourself.

It has a certain charm to say Pascal, because it sounds like Pascal almost – and he couldn’t have said it better.

I have a joy of invention. I have the joy of storytelling in me – which is why I make films. It’s not for the sake of cheating or misleading anyone (and that’s why I tell certain publications, ‘I made this up’); it’s actually to help you to rise above your existence into the realm of something cosmic, something sublime, something horrifying, something of great beauty.

You have told the story of how in 1974, when you were told that your mentor [the great German film historian] Lotte Eisner had had a massive stroke and you must go to see her before she died, you ‘grabbed a bundle of clothes’ – and set off from Munich to Paris on foot! You knew, you have said, that she wouldn’t die before you got there. Now, that’s an expression of faith in something –

The Catholic church has a wonderful term for it: Heilsgewissheit, the certainty of salvation.

But, as you’re not a believer, what was it that you were expressing faith in?

Partly in myself, that I would defy death by walking – in the book I published [about the journey], Of Walking in Ice, I say: ‘When I walk, a bison walks. When I stop, a mountain stops.’ And I come, I come with the necessary weight and the necessary determination and the necessary faith of the pilgrim and the necessary defiance of death, and I knew she would survive. Which she did, for nine more years, until she finally asked me: ‘Can you take this spell off me?’ I said, ‘Yes, it’s taken off’ – and then she died, then she actually died!

Did you really believe that your decision to walk to Paris could keep her alive?

Sometimes I can’t help feeling that I am touched by the grace of God – even if I don’t believe in God. Perhaps it is a distant echo from my religious phase

There was not much thought, I just set out and I knew I had to do it and she would not die because I was coming. But I was not coming by plane; I was stomping one million steps towards her.

You must have been very confident, because you even made a detour to see Troyes Cathedral.

Yes. The strange thing is, I never had any contact [with her], I didn’t know if she was still alive or not. I walked a straight line – I took a compass reading and I walked straight through forests, over mountains and rivers – but, towards the very end, I allowed myself to make a detour of 20 or 30 miles to visit the Gothic cathedral at Troyes, because I’m a great admirer of the medieval writer Chrétien de Troyes. It was a very, very intense experience.

In your so-called Minnesota Declaration of 1999,12See bit.ly/2j9mRLE. you say: Walking is virtue –

And tourism is sin.

You have been walking very long distances ever since you were a teenager. Can you say a little about how it has changed your view of the world?

It’s not easy to answer. I only know, with absolute certainty – I have to say it in a dictum: The world reveals itself to those who travel on foot.

That’s it. No further explanation. My understanding of the world, my reading of the world… The world has declared itself, it has shown itself. And this is why I tell film-makers: Walk a thousand miles. It’s much more worth than three years’ film school.

There’s a lot of serendipity in your films, I think, and in Into the Abyss there’s an extraordinary moment when you say to the chaplain at the ‘death house’, ‘Tell me about an encounter with a squirrel!’ and he comes apart.

He was speaking about the greatness of God’s creation and the mercy of God and Paradise for everyone – forgetting that there is such a thing as hell in Christian belief – and he was like a phony television preacher and I knew I had to shake him out of it. So, when he told me that sometimes on the golf course he would see a squirrel or a deer looking at him with big eyes, I asked him: ‘Tell me about an encounter with a squirrel!’ And only by knowing the heart of men would I ask a question like that, because it breaks him open. Why, I cannot explain, but it does. All of a sudden, he becomes profound. He becomes a deep human being.

One of the most celebrated sequences in your work is the dancing chicken at the end of Stroszek. In your commentary on the DVD you say that capturing that on film was a kind of blessing.

Yes. Sometimes I can’t help feeling that I am touched by the grace of God – even if I don’t believe in God. Perhaps it is a distant echo from my religious phase.

Yet in the Minnesota Declaration you say: ‘We ought to be grateful that the universe out there knows no smile.’ Isn’t there a contradiction between a heartless universe and something, whatever it may be, that keeps giving you these gifts?

Well, it may be despite the universe, despite creation. You have to wrestle meaning from it, you have to wrestle a minimum amount of dignity from it, a minimum amount of joy, a minimum of grace upon you.

But that ‘grace’ is wrestled from it, it isn’t given?

It doesn’t give it to me. You have to wrestle it from it!

Thank you for giving us so much of your time…

We should have spoken more about the Bible! I find it very relaxing, a real relief, that we are talking not just about movies but about the universe, about creation and whatever. Religion, in fact. We have covered some good ground, some basic questions I have struggled with.

This edit was originally published in the May 2012 issue of Third Way.

To make sure you hear of future interviews in this series, follow High Profiles on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

| ⇑1 | His 1972 film starring Klaus Kinski as the Spanish conquistador Lope de Aguirre, who leads his men to their eventual destruction in a futile search for the city of El Dorado |

|---|---|

| ⇑2 | His 2010 documentary, shot in 3D, about the prehistoric paintings in the Chauvet caves in southern France |

| ⇑3 | Jeder Mensch ist ein Abgrund; es schwindelt einem, wenn man hinabsieht. |

| ⇑4 | Jeremiah 17:9 (KJV) |

| ⇑5 | Into the Abyss: A tale of death, a tale of life, released in British cinemas in March 2012 and on DVD a fortnight later |

| ⇑6 | Screened on Channel 4 on 22 & 29 March and 5 April 2012 |

| ⇑7 | The self-styled emperor of the Central African Republic, who was the subject of Herzog’s 1990 documentary Echoes from a Sombre Empire. Herzog has asserted that he was a cannibal and ‘seemed to represent the kind of human darkness you find in Nero or Caligula, Hitler or Saddam Hussein’ (Herzog on Herzog). He had permission to interview Bokassa in prison, but was expelled from the CAR before he could. Bokassa was later released and eventually pardoned. |

| ⇑8 | One of the principal architects of the Holocaust, who was tried in Jerusalem in 1961 and hanged the following year |

| ⇑9 | Faber and Faber, 2002 |

| ⇑10 | A ‘documentary’ shot in the burning oilfields of Kuwait in 1992 |

| ⇑11 | An 18-minute ‘documentary’ made with John Tavener for the BBC in 2001 |

| ⇑12 | See bit.ly/2j9mRLE. |

To find out more about the agenda behind our interviews, read our manifesto. To access our archive of more than 260 interviews, see the full list.

Biography

Werner Herzog was born in 1942 and grew up in the remote village of Sachrang in the Chiemgau Alps. When he was 12, his family moved back to Munich, where he attended the Classical Gymnasium until 1961. He won a prize for a film script at the age of 15.

He read history and German literature at Munich University (despite winning a Fulbright scholarship to study at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh).

He made his first short, Herakles, in 1962, and soon after won the Carl Mayer Award for his screenplay for Signs of Life. He set up his own production company, and shot Signs of Life in 1968, winning a Silver Bear for best first film at that year’s Berlin Film Festival.

He has since made 16 more features: Even Dwarfs Started Small (1970), Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974), which won the Grand Jury Prize at Cannes in 1975, Heart of Glass (1976), Stroszek (1977), Nosferatu the Vampyre and Woyzeck (both 1979), Fitzcarraldo (1982), which won the prize for best director at Cannes, Where the Green Ants Dream (1984), Cobra Verde (1987), Scream of Stone (1991), Invincible (2001), The Wild Blue Yonder (2005), Rescue Dawn (2006) and [The] Bad Lieutenant and My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done (both 2009).

His ‘documentaries’ include Fata Morgana and Land of Silence and Darkness (both 1971), The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner (1974), Wodaabe: Herdsmen of the Sun (1989), Lessons of Darkness (1992), Bells from the Deep (1993), Little Dieter Needs to Fly (1998), My Best Fiend (1999), Wings of Hope (2000), Wheel of Time (2003), The White Diamond (2004), Grizzly Man (2005), the Oscar-nominated Encounters at the End of the World (2007), Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010) and Into the Abyss (2011).

He has written all but three of his films, Scream of Stone, Bad Lieutenant and My Son, My Son…, which he co-wrote. Among other books, he is the author of Of Walking in Ice (1980) and Conquest of the Useless: Reflections from the making of Fitzcarraldo (2009).

Since 1986, he has directed opera all over the world, including Doctor Faustus, Lohengrin (in Bayreuth), The Flying Dutchman, Tannhäuser, The Magic Flute, Fidelio (at La Scala) and Parsifal.

He has been married three times and has two sons and a daughter. He now lives in Los Angeles.

Up-to-date as at 1 April 2012