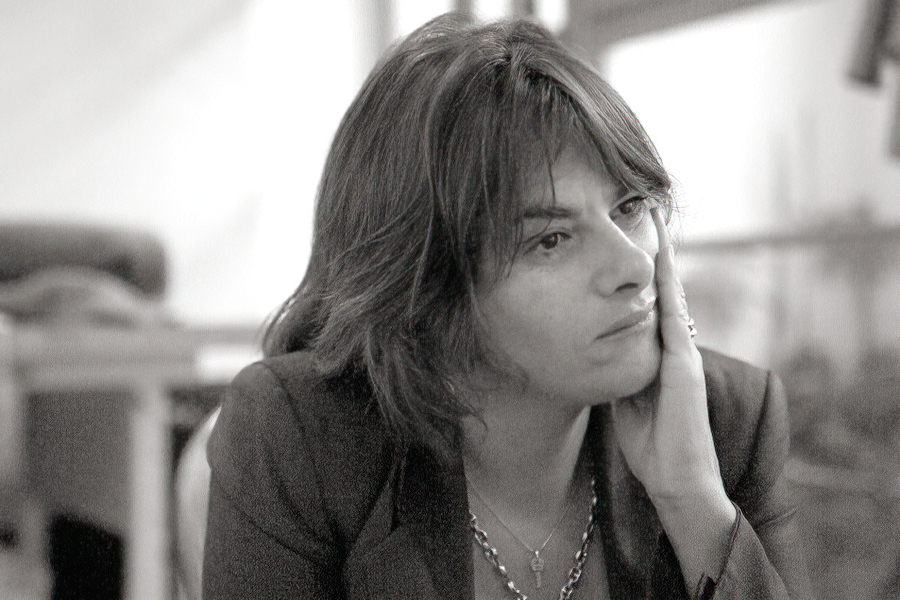

Tracey Emin

was one of the ‘young British artists’ who achieved notoriety in the 1990s. David Bowie once described her as ‘William Blake as a woman, written by Mike Leigh’.

Simon Joseph Jones caught her in her studio in east London on 31 October 2006. The next year, she was elected a Royal Academician and represented Britain at the Venice Biennale.

Photography: Andrew Firth

I think you once said that interviewers keep talking to you about sex and you wish they would ask you about God.

Yeah, but I’m using ‘God’ as a term for faith. God is too big a subject, really.

I believe you went to a church school.

Anglican – but High Anglican, not just, like, Church of England. From when I was little, I had assembly every day, I had prayers every day, I had grace every day, and scripture was part of the school curriculum, and every religious festival. Up until we were 10, and then it all kind of changed radically. The teachers were something from the Victorian era.

Yet your home wasn’t religious as such, was it?

No, not even the slightest bit. But I went to Sunday school, when I was about nine, of my own accord. And also, like, a Jesus art club when I was about 11. And it was all my own doing. My mum hated it. It wasn’t ‘Oh, isn’t she good?’

I think part of that was because when my mum was little she’d gone to Sunday school and been told that Jesus was everywhere, and she was quite horrified at the idea of this strange man following her home. And also my dad – you know, he’s a Muslim but he’s not practising. He only had two years’ education, at Qur’an school when he was little. So, it was kind of weird.

But your mum was interested in spiritualism?

Yeah. My mum and my nan and all that, they were really into it, same as me. Give them a ouija board any day, you know? Or Tarot cards or anything like that – a medium or anything.

So, there was an awareness that there is something other than the material universe?

That’s the problem with religion: the moment you start thinking, ‘Every single word of this is the truth,’ we’re all completely fucked. Instead of thinking, ‘Let’s update this fantastic fable for our times!’

Yes. But I’ve known that – actually known it – since I was about three. When I was little, I was always aware of other things: other atmospheres, entities, feelings. Like, I was aware that I wasn’t alone in a room, even when there was no other human beings there. When you’re a child – especially when you’re a toddler – you’re much more susceptible to that kind of thing because you just accept that it’s there.

Presumably, if you mentioned such things in Sunday school or at your church school, they would have put a different interpretation on it.

I think I didn’t really talk about it. And what with the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost, you know, for me it was all completely mixed up anyway.

But I didn’t see the Bible and everything as, like, a religion or a belief, I always saw it as a story, like a fantastic myth. The parting of the sea, you know? Wow! The fish, the loaves, everything. It was all a visual thing – like when you read a good book and you visualise it all. It was that kind of thing.

Is there a connection here with your interest in both Byzantine art and Renaissance religious art?

Yeah, they tell really good stories. Like the Annunciation. Wow! I’d like one of them. It’s like uplift of the spirit and everything. But it doesn’t have to be the divine truth.

That’s the problem with religion: the moment you start thinking, ‘Every single word of this is the truth,’ we’re all completely fucked. We can see it happening around us. Instead of people thinking, ‘This is really useful. It could be teaching us something. Historically, it’s amazing how this could have been written at that time. Let’s update this fantastic fable for our modern times!’… I mean, fucking hell, mid-west America, you know? If anyone thinks that Islam is scary, they ain’t seen anything.

Religion is, like, becoming totally corrupted by power – and not the power within. It’s like this big, surging mass, swarming around the world. It’s not a very pleasant thing – unlike me trotting off to Sunday school when I was little, thinking, ‘This is really nice. I can learn something here.’

The Byzantine artists, and even, I suppose, those of the Renaissance, would have had a very different understanding of what the artist is.

Yes, they’d have been, like, just a messenger. But in a way I think being an artist is like being a messenger: you have something to say and people can pick up on it. For me, art is about communication – in the times that we’re living in, that is what it must be used for. And it’s working really well for me.

I believe – even though I’m really self-indulgent – it’s like if you’ve been born with a fantastic voice, you have to sing, and if you didn’t it would be an absolute waste, almost a crime. And even though [other] people may not perceive my art in that kind of way, I do. It’s a fantastic gift. It’s a really brilliant thing, to wake up every day and be creative and get away with it. What a life! It’s brilliant.

But as well as being the messenger you’re also the message to some extent, because a lot of your art is personal to you –

Yeah, but it relates to other people, doesn’t it?

Yes, of course.

For me, art isn’t a job, it isn’t what I do: it’s who I am. If I’m not making the art, I’m not who I am and I start to feel lost. Whereas when I’m being creative, I’m anchored. I feel solid and I feel good

I write a column for the Independent every Friday, and one of my friends, she said to me, ‘I get so sick of reading your column, Tracey! No sex for two years, blah blah. Ohh, no sex again…’ I said, ‘Hey, Janet’ – it was Janet Street-Porter, actually – ‘there’s loads of people out there that don’t have sex for two years, but people will just assume that someone like me did. Millions of people that are married or living together haven’t made love not for two years but for five years, or 10 years. A lot of the world is not making love and they think there’s something wrong with them, and there isn’t. So, it’s something that other people can relate to.’ And she said, ‘Hey, you’re right.’

And it’s the same with the art, you know? Not everyone, but a lot of people know what it’s like to feel really alone, but not everyone has the courage to say it. I was stood up last year – I had a rendezvous in a hotel – in another country, as well – and I was waiting there, waiting and waiting and waiting, thinking, ‘Maybe they missed the flight, maybe this or maybe that’ – and I called them and called them, and the next day I called them and called them and they didn’t turn up. And I just lay there and cried.

And the thing is, I don’t know anybody else that has happened to, but I bet it’s happened to tons and tons of people, do you know what I mean? And if all these people got together, they’d be really laughing. Everyone would have all these stories.

Does that mean that the sides of yourself you make public are the sides you believe are universal?

I believe a lot of them are universal, yeah. Definitely.

Your work is frequently called ‘confessional’. Is that a word you’re comfortable with?

I don’t think I’ve ever confessed to anything in my life. I believe that confessing is like when you know you’ve done something wrong but you haven’t admitted it and then you go and tell someone and it is such a relief, to get the weight off your shoulders; and then you can start dealing with the guilt and the wrongness of it and can start trying to put it right. With me, the moment I’ve done something wrong, I know I have. I know I have. And it’s at that point that I immediately start to put it right.

What am I [supposed to be] confessing? That I was raped when I was 13? No, actually, I don’t have to confess that. It’s something that happened to me – I didn’t do it myself. It’s a different thing.

Do you think you have been misrepresented, then?

No, I think they just say ‘confessional’ because it’s an easy term for them. To them, it means that someone reveals things that other people wouldn’t. Well, of course they’ve got completely the wrong word.

You said once that when you are making art you feel as if it makes you a better human being.

Yeah, you know what? I worked this out. For me, art isn’t a job, it isn’t what I do: it’s who I am. So, if I’m not making the art, I’m not who I am and then I lose direction and I start to feel lost. I start to feel unworthy – not justified in even being here. I’m all at sea, intellectually, emotionally, socially. Whereas when I’m being creative, I’m anchored. I feel solid and I feel good. It sounds like a really basic thing, but it’s taken me years to work that out.

The people who did those things to me when I was little are wrong people, do you know what I mean? Their whole being was incorrect. And me hating them isn’t actually going to change that at all

It feels to me that in your art there is a striving to get to a place where you feel loved and respected and whole. But it also strikes me (given some of the stuff that is so difficult to read in your memoirs) that there is a lot of forgiveness in your work – especially towards your parents.

But my parents didn’t actually do anything wrong. It just wasn’t the best job they ever had, being parents. It wasn’t their vocation. But that doesn’t mean they didn’t love me. They loved me, really loved me. My mum just wasn’t really cut out to be a mum.

Many other people would blame their parents if they had experienced the degree of abuse that you did.

Yeah, but my mum and dad weren’t the abusers. It makes a big difference. They were bystanders, unfortunately. They should have done something about it, but they were oblivious, or in denial. My dad wasn’t around anyway, and when you see your dad maybe once a year… ‘Hey, Dad, I forgot to tell you, I’m being sexually abused. I’m really glad you turned up today. Can you go and have a go at someone?’ It doesn’t work like that, does it? You’re just really happy to see your dad.

And my mum was always out working, working, working. She worked as a chambermaid and in a nightclub as a waitress, so it meant she was busy from six until two in the morning. She’d come home in between in the day, but we spent a lot of time on our own. And also we didn’t have boundaries – like we didn’t have a time to go to bed, and if I didn’t want to go to school, I didn’t have to go.

I would say, too, that in your work there is a strong sense of redemption, in the sense that you take your past and make something positive out of it.

Well, it’s like in the last 15 years I’ve had two relationships and these men are two of my best friends. One of them was terribly unfaithful to me – really outrageously unfaithful – and people say, ‘How can you still be friends?’ And I say, ‘Just because we’ve stopped loving each other in that way doesn’t mean we can’t go on loving each other in another way.’ I don’t forgive him for what he did, but our love grew into something else, and what he did is not important in comparison to the friendship we have now. It’s not about forgiving, often, it’s about growing and developing and understanding what the situation was.

The stuff that happened to me when I was little – the people who did those things are wrong people, do you know what I mean? Their whole being, their whole self was incorrect. They had a serious problem. And me hating them, really hating them, isn’t actually going to change that at all.

So, do you not feel any hatred?

I feel a really big sadness for my lack of innocence, and my self-loathing and things I’ve gone through, which I still can go through. But I’ve got to remember that it’s not a downward spiral. I’m somewhere nicely at the top now and I don’t have to be dragged down if I don’t want to be.

By ‘redemption’, I meant that in your work you seem to be dealing with your anger about your past.

Yeah, but that’s good, isn’t it? It’s good that I’m angry in my work, isn’t it?

For a lot of artists, words don’t have any meaning whatsoever – they can’t even string a sentence together. But for me words are important. Even with a drawing, the title’s really important

It’s also about taking control, isn’t it? It’s like – (This is a terrible thing I’m going to say. I’ve never done this, but I’ve thought about it.) If someone is really unfaithful to you and you just get a big spray can and you write, ‘I know what you’re doing’ on the road in front of their house, so that when they come out in the morning… You know? Wow! The hurt and the anger it would release as you’re doing it! But you’re not actually hurting anybody.

Someone would be really pissed off because you have ruined the street or whatever – I totally understand that. But it’s much better than going and hitting someone, or harming yourself, to get revenge, do you know what I mean? I can get a giant canvas and I can draw this stuff, or write this stuff, and it’s a really good thing for me.

Words are quite important to you, aren’t they?

For a lot of artists, words don’t have any meaning whatsoever – they can’t even string a sentence together. But for me words are important. Even with a drawing, the title’s really important. And then the neons I make, of course they’re nearly all words – but they have to warrant being made in neon.

Could we talk about a particular title –

‘I Need Art Like I Need God’.

In the 21st century, if someone calls an exhibition ‘I Need Art Like I Need God’, everyone assumes it’s a clever way of saying that they don’t need art. But –

That wasn’t the case at all, no.

I had absolutely no money – none, none, none. This was in about 1995. Someone had sent me £5 to get a film to take slides, and it was all I had; and my mum had sent me the train fare to go down to Margate so I could stay with her. My mum had no money either, but at least she had social security or a pension or whatever, so we could eat.

So, I was going down on the train and I had no intention of getting the film to do the art project – I thought I would just do it later, or wing it. And all the time I was on the train there was this blue thing in front of me but I paid no attention to it, but then when I got off I picked it up and it was a cheap plastic camera. And I thought, ‘Right, I won’t hand it in yet. I’m going to buy some film, take some slides of Margate and then hand it in.’ And it really perked me up. I’d been really in the doldrums on the train.

It was a day in March, with a fantastic blue sky – I mean, really, really amazing – and the spring tides were so high that even from the top of the cliff you could feel the spray coming up. It was just gorgeous, you know? The sea was like an aquamariney kind of colour, with dark shadows in it, and there were these weird clouds going across – the whole thing was so beautiful it was just incredible.

And then I was thinking, ‘Wow! I’m so lucky I found the camera and I had the five quid.’ And I was thinking, ‘You forget how small you are in the world and you’re feeling sorry for yourself and you are surrounded by all this nature and all this beauty and this is historic, this fantastic moment.’ I picked up a piece of chalk from the cliff and I wrote: ‘I need art like I need God.’

And I didn’t know I was going to write that. You know, I could have wrote: ‘Tracey Emin was here.’ (I probably did later on.) And then I took a photo of it, and I thought, ‘That’ll make a really good title for a show.’ And at that point I had no intention of making any art again, no intention of showing. I felt very despondent. I felt like art had left me – you know, like a lover that leaves you and then they come back and you realise that you really love them and they really care about you. It was like that.

And I didn’t know I was going to write that. You know, I could have wrote: ‘Tracey Emin was here.’ (I probably did later on.) And then I took a photo of it, and I thought, ‘That’ll make a really good title for a show.’ And at that point I had no intention of making any art again, no intention of showing. I felt very despondent. I felt like art had left me – you know, like a lover that leaves you and then they come back and you realise that you really love them and they really care about you. It was like that.

And it was also saying that the times when you feel you’ve lost everything are when you’ve lost faith or whatever, and when it all returned to me, this great big thing through nature, it was just brilliant. And I suppose my stream of consciousness was taking the slide film, thinking, ‘This is art,’ and then the nature, thinking, ‘This is God. This is amazing,’ and then that’s when I wrote the sentence.

And a few months later David Thorpe from the South London Gallery come to see me and said, ‘I’d really like you to do a show. Have you got any ideas?’ And I said, ‘Yes. I’ve got a show and it’s called “I Need Art…”.’ And that was it.

Some Christians might interpret that story in terms of Providence, but for you it was nothing so specific. What are you saying you have faith in?

Well, I felt like quite an enlightened spirit at that moment. I felt very lucky, I felt very lifted. I didn’t feel alone. I felt insignificant compared to the cliffs and the sea and all that stuff, but I felt part of it.

It’s a brilliant feeling, to feel part of something and not feel alienated. Often if you have some kind of depression or whatever, you feel alienated from everything. A lot of people who are very sad or depressed can’t see anything beautiful at all. I feel that all of us are connected to something and to someone. None of us are alone. But sometimes those links get broken and that’s when we feel really lost.

So, your faith is a kind of pantheism.

I really love Spinoza.

Right.

For me, Spinoza is fantastic. It’s like poetry. You don’t have to know anything about philosophy – you just read it and you think, ‘It’s really beautiful.’

I understand that you also like Nietzsche.

Yeah, because it’s the complete antithesis, isn’t it? I think it’s like reading pornography. It’s like just for young boys – oh, it’s so stupid, it’s like – huh! I’d read it and it would just make me really angry – but I’d turn the next page, and the next, and the next…

Also, Nietzsche is very much about being strong, you know, and not giving up – which is really important. I still think it’s really puerile in comparison to someone like Spinoza, but still Nietzsche’s good to get the blood flowing, to get the adrenalin going.

At the end of the video piece Why I Never Became a Dancer, you listed the boys who shouted ‘Slag!’ at you and destroyed your confidence. Nowadays, I suppose, the Daily Mail says much the same sort of thing in slightly more sophisticated language –

Or not.

Do its comments have a similar impact on you?

No. The Daily Mail is just a sad part of Middle England, really.

When I got nominated for the Turner Prize, I was asleep in front of the telly and Channel 4 News came on and I saw my buttocks on the screen. Out of all the images they could have used, they used [that one]

And they weren’t boys: these people were 19 or 20, or 25. It wasn’t like it was a school playground thing. It was worse than that. And it was only because I’d slept with a few of them, do you know what I mean? I think it was strange they should call me a slag, actually, when all I did was slept with them. It wasn’t like the crime of the century.

Your gender has a lot to do with the way the Mail responds, doesn’t it? And then there was the whole misreading of Everyone I Have Ever Slept With…1Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995 (1995), a small tent embroidered inside with the names of everyone Emin had ever been asleep with, including her twin brother and her two aborted children, was featured in the 1997 exhibition ‘Sensation’ at the Royal Academy in London. It was destroyed in a warehouse fire in 2004.

Yeah. The people who went inside the tent understood that it was all about intimacy. I used the word ‘sleep’ to get people into the tent, but when they came out they felt very differently.

I made the tent before anyone knew who I was, and if I’d remade it after it burnt – God knows how – I’d have got a couple of million pound or something. They rang me and asked, ‘Is there no chance?’ and I said, ‘No way!’ The tent had its meaning because no one knew who I was – it was almost like a kind of nutty thing to do; but if I did it now it would just be, like, really gratuitous, and slightly tacky.

So, the Mail could say that you did expect people to misread the title.

Yeah, but they didn’t look at the work. Like, when I got nominated for the Turner Prize [in 1999] I was asleep in front of the telly and Channel 4 News came on and I saw my buttocks on the screen. Huh? Oh yeah, I’ve been nominated for the Turner Prize, yeah. Do you know what I mean? Out of all the images they could have used, they used the one of my buttocks. And then next day, you know, in the Star or whatever there’s a picture of me on page three from a project I did of myself naked. I don’t know how they got it. Now, someone could say, ‘But you showed that image in a gallery.’ Yeah, in a context where the viewer goes expecting to see art. It wasn’t made for page three of any paper.

Does this kind of reaction affect your work?

I have to be really careful that I don’t censor myself. If I started thinking, ‘Oh, this could end up in the Mail, or on page three…’ Like, if you Google me, there’s a whole bloody porno site on me. If I start thinking like that, it’s like… I travel on the Tube a few times a week and I always get approached and people try to talk to me and the other day someone tried to kiss me, and it’s always a little bit hassly – but it’s not as hassly as getting in a cab during the rush hour and it costs me 18 or 19 quid and I have to have a really long conversation about art. I have to weigh up the pros and cons; but what I have to do is do the journey. That’s what I have to do. And it’s the same with my art.

If I start thinking, ‘If I make this and it ends up there…’ I won’t make anything. And even if I want to make something really passive, you know, I could start thinking, ‘Oh, this isn’t what people expect of me. They want me to be controversial and highly emotive.’ You just make what you want to make. If you allow all the things that are outside to affect you, you’re not going to do what you have to do. You don’t make your journey, you end up staying at home.

So, when people say you are just out to shock –

No.

A lot of people who make a living as artists have never made a piece of art in their lives. Do they really believe in what they’re doing? If they really tell the truth, they will say: ‘No. I just think it looks nice’

Not even at a conceptual level, like Duchamp?2Marcel Duchamp shocked the art world in 1917 when he submitted for exhibition in New York a porcelain urinal which he had signed and titled ‘Fountain’.

No, no. I mean, the only conceptual thing about my work is the fact that I think about it before I make it. I think of a title, I think of a meaning, I think of the dialogue that I’m having with myself. Otherwise, I’m like a hardcore Expressionist, you know?

The fact that there’s a degree of calculation involved is because I’m intelligent. I’m not a naive artist – if I was, you wouldn’t be interviewing me.

Do you subscribe to the Romantic idea of the artist as a rarefied soul? Is there something different about you that makes you an artist?

Yeah, I think there is. But not all artists.

Right…

There was all that research recently about artists having schizophrenia. (Apparently they’re fantastic in bed but they also have schizophrenia. Hey! Look on the bright side!) I don’t think it’s schizophrenia at all – I think that was just really mean – but I do think there’s a kind of existential thing of being able to be outside looking in and inside looking out, almost at the same time.

I think there are also people who may have never made a piece of art in their life but they have a really fantastic artistic soul and it comes out in many other, different ways. This sounds really stupid, but you can have a nurse, for example, and everything she does is with such panache, such flair, such caring, such humour, such diversity, such a different being, that she’s enlightened in some way. Do you know what I mean? I don’t think it’s just artists.

In the same way, I think there is a lot of people make a living as artists who have never made a piece of art in their lives.

How can someone have a career as an artist and yet never have made a piece of art?

I’m being facetious, aren’t I? I’m being really honest and really facetious. There are lots of people who make what we call ‘art’, it looks like art, it’s in the gallery… (It’s what everyone says about me, people who don’t like what I do, or don’t believe it. But there’s a level of sincerity.) You could say to someone, ‘Tell us the truth. Do you really believe in what you’re doing?’ And if they really tell the truth, they will go: ‘No. I just think it looks nice.’ They’re only interested in how it looks on the surface, you know? What’s it about? ‘Nothing. I just like the pattern.’

I’m not saying they aren’t great interior designers. What I’m saying is, there are different levels of sincerity with art. You can even have someone who makes art that believes that art should not be sincere, that art should only appear on the surface; but this person has a whole dialogue, a whole formula, and they passionately believe in it – like Mondrian.

But if you don’t have any of that, it’s just superficial, really.

Does that level of sincerity account for your emotional attachment to your work? You’ve talked about the first time someone bought one of your blankets.

Yeah, and I started crying. I didn’t really seriously think anyone would ever buy it. I was in New York and I had it on my bed in the hotel. But of course them buying that blanket then enabled me to pay my bills and decorate my flat and get a new fridge.

If you’ve ever been poor and suddenly you can leave your heating on, you can eat the kind of food you really want to eat, you can take [your bike] into the bike shop and get it fixed – oh, it feels fantastic!

To what extent does it validate you as an artist that you are famous and people buy your work?

If you’ve ever been poor – I mean, one-bar-electric-fire poor – and suddenly you can leave your heating on and you can be warm and cosy, you can eat the kind of food that you really want to eat, you get a puncture on your bike you can take it into the bike shop and get it fixed (Do you know what I mean? I’m not talking on the grand level) – oh, it feels fantastic! So, the validation is not ‘Oh, I sold loads of work, I’m really wealthy.’ It’s ‘Phew! I can get on with my work.’ That’s what’s brilliant about it.

OK, that’s material reassurance. But you’re offering an artistic vision and people out there say, ‘We love this and we want to spend money on it – or we want to give this woman a room on her own in the Tate or whatever.’ Is that arrival?

Yes, of course it is, yeah. It’s arrival in the first-class lounge, actually. You’ve really arrived.

Does it bother you, if there are ‘artists’ out there who have never made a piece of art in their lives, that some of them also get some kind of validation?

Doesn’t bother me. I can be infuriated when something passé and conservative rises, rises, rises above the ranks. I think, ‘Well, the reason that rose above the ranks is because it’s not touching anything. It’s just floating. Whereas the people that are banging and clashing and making people perceive the world differently, or art differently, they get pushed down. That can irritate me.

But I’m more interested in what I’m doing, you know?

What would you say is the measure of true art?

It should make people look at life differently. Like, the first time I went to the Tate I was 22 and I really only liked figurative Expressionist paintings – that’s where I was. I came across a pink-and-yellow painting by Rothko.3Untitled (c1950–2)

And I looked at it, and I sat down and looked at it and I started really welling up inside and I cried. I didn’t know anything about Rothko, I didn’t like abstract painting, I certainly wasn’t into insipid colours like pale pink and wishy-washy yellow – I liked black and red. But this painting had this really strong effect on me.

It was later that I looked up Rothko and discovered that he was devoutly religious and then did all the figurative work and then all the abstract work and then committed suicide. Hey presto! I had felt it looking at this painting. And I thought, ‘Wow! That’s almost like magic, that I could feel that from looking at that work without knowing anything about him.’ And that’s what art should do.

What would you say to people who don’t think they understand art?

It’s really simple: you look at it and you think about how it makes you feel. Once you’ve done that, you’ve understood it. It doesn’t matter if someone says it’s got all this art theory behind it, or someone says, ‘Oh no, you’ve got it all wrong.’ You haven’t got it wrong. It’s how you want to interpret it.

And if you feel nothing, if it did nothing for you, you walk on and you look at something else until it does happen.

This interview was published in the December 2006 issue of Third Way.

To make sure you hear of future interviews in this series, follow High Profiles on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

| ⇑1 | Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995 (1995), a small tent embroidered inside with the names of everyone Emin had ever been asleep with, including her twin brother and her two aborted children, was featured in the 1997 exhibition ‘Sensation’ at the Royal Academy in London. It was destroyed in a warehouse fire in 2004. |

|---|---|

| ⇑2 | Marcel Duchamp shocked the art world in 1917 when he submitted for exhibition in New York a porcelain urinal which he had signed and titled ‘Fountain’. |

| ⇑3 | Untitled (c1950–2) |

To find out more about the agenda behind our interviews, read our manifesto. To access our archive of more than 260 interviews, see the full list.

Biography

Tracey Emin was born in 1963 to an English mother and a Turkish Cypriot father, and brought up in Margate – in her parents’ hotel until the age of seven, when the business crashed. She left school finally at the age of 15.

After starting but not completing a diploma in fashion at Medway College of Design, she did a foundation course at the John Cass School of Art in London and then studied fine art at Maidstone College of Art. She graduated in 1986 with a first-class degree, and went on to take an MA in painting at the Royal College of Art in 1989.

In 1993, she opened The Shop in the East End of London with her fellow artist Sarah Lucas, selling work by both of them. She ran her own personal gallery, the Tracey Emin Museum, in London from 1995 to 1998.

Her art has encompassed painting, drawing, video, installation, photography, neon, needlework, sculpture and live performance. Her first major show was at the White Cube Gallery in London in 1992, which two years later presented her first solo exhibition, ‘My Major Retrospective’. Since then, she has been widely exhibited around the world, including solo shows in Amsterdam, Berlin, Bremen, Brussels, Helsinki, Istanbul, Munich, New York, Paris, Rome, Stockholm and Tokyo.

Her solo shows have included ‘Exploration of the Soul’ (1994), ‘Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made’, ‘The Aggression of Beauty’ and ‘It’s Not Me That’s Crying, It’s My Soul’ (all 1996), ‘I Need Art Like I Need God’ (1997), ‘Cunt Vernacular’, ‘Sobasex’ and ‘Every Part of Me’s Bleeding’ (all 1999), ‘What Do You Know about Love’ and ‘Love Is a Strange Thing’ (both 2000), ‘You Forgot to Kiss My Soul’ (2001), ‘I Think It’s in My Head’ and ‘This Is Another Place’ (both 2002), ‘Menphis’ (2003), ‘Can’t See Past My Own Eyes’ and ‘I’ll Meet You in Heaven’ (both 2004), ‘Death Mask’, ‘When I Think about Sex…’ and ‘I Can Feel Your Smile’ (all 2005) and ‘More Flow’ (2006).

Group shows her work has appeared in include ‘Minky Manky’ (1995), ‘Sensation’ (1997), ‘Personal Effects’ and ‘Made in London’ (both 1998), ‘Sweetie’, ‘Temple of Diana’ and ‘Now It’s My Turn to Scream’ (all 1999), ‘Art in Sacred Spaces’ (2000), ‘Trans Sexual Express’ (2001), ‘The Glory of God: New Religious Art’ and ‘Face Off’ (both 2002), ‘Stranger than Fiction’ (2004) and ‘London Calling’ (2005). She also had works in the 2001, 2004 and 2005 summer exhibitions at the Royal Academy in London.

Her notable works in film and broadcast media include Why I Never Became a Dancer (1995), CV (1997) and Top Spot (2004).

Her publications include Exploration of the Soul (1994), Absolute Tracey (1998) and Strangeland (2005). She wrote a weekly column for the Independent from 2005.

In 1997, she won both the International Award for Video Art in Baden-Baden and the Video Art Prize in Stuttgart. Her installation My Bed was shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 1999 (and was subsequently bought by Charles Saatchi at auction for £150,000).

In 2005, the BBC commissioned her first piece of public art, The Roman Standard, for Liverpool’s Art05 celebrations.

Up-to-date as at 1 October 2006