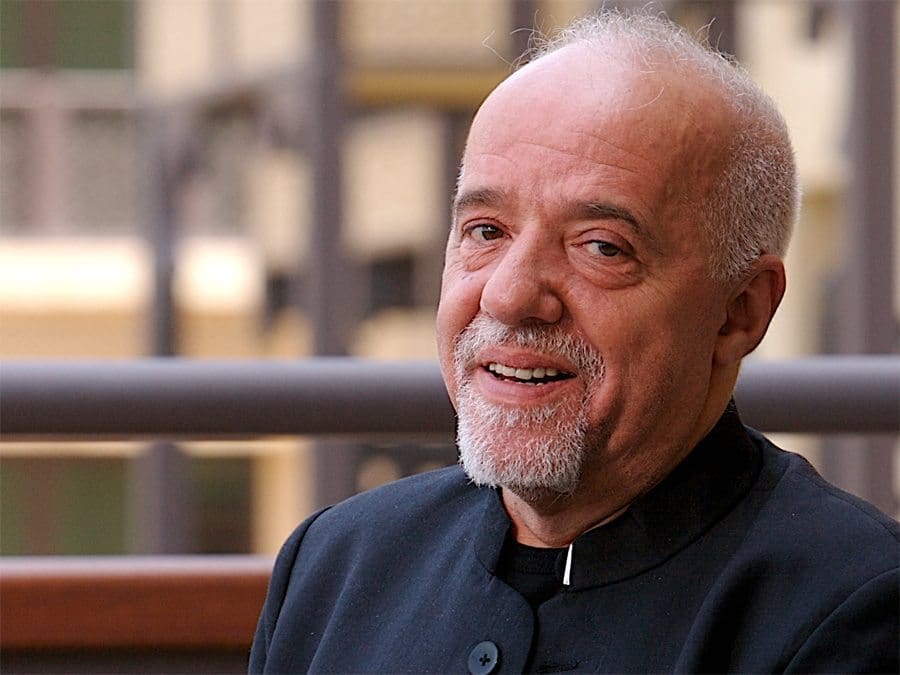

Paulo Coelho

is one of the world’s most popular living authors – The Alchemist alone has shifted tens of millions of copies. Brian Draper rang him in Geneva on 12 March 2010 to test his mettle.

At the end, Coelho remarked that he rarely gave interviews – he had given only two in English that year – but ‘when I saw your magazine, I said, “That [should] be a very interesting and challenging interview” – and it was!’

Photography: Paul Macleod

You have said that it took you just 14 days to write your best-seller The Alchemist. Was that because (as you have recently remarked) it was already written in your soul?

Let me try to explain myself better. I believe that each one of us has a spark of the divine light to manifest. It is our task here on this earth, and our human condition demands – demands – that we do it, to justify ourselves. So, my dream since I was very, very young was to be a writer, though I – well, I was procrastinating, because sometimes you fear to face your reason to be here.

When I decided to burn my ships and start writing, I was 40 years old. I wrote about my first experience on the road to Santiago [de Compostela, in The Pilgrimage1Published in Portuguese in 1987 as O Diário de Um Mago, and originally published in English, in the United States in 1992, as The Diary of a Magus]. And then, for my second book, I decided to write a metaphor of my life, never knowing, of course, that this was going to touch many souls. So, The Alchemist [1988] was just a matter of looking back and finding a good story, finding a metaphor, for me to understand myself. And then it took me, yes, two weeks to put it down on paper; but the book was there long before, because it is my life.

Is writing for you simply a matter of finding the treasure that is buried within you? Or is it more a matter of craft, a labour of love?

I would say that [love] has to do with everything we do. First, you have to hear this call. You know, when you are close to something that justifies your life – it can be gardening, it can be cooking, it can be driving a taxi, it can be whatever you do with love – the clue is exactly that: love. I don’t think that a writer is better than anybody else. Everything that you do with enthusiasm, you are really manifesting God.

The next step is to learn the craft. So, for writing, first I had to read. You don’t learn writing from courses or workshops – I don’t believe in them. You learn how to write by reading other writers, people who have tried to share their souls, their experiences, whatever they have, with their fellow human beings. Then you have to make some choices: What shall I write about? What are my main questions? And then you start to develop your own technique. You start innovating, in the sense that you try not to repeat what other people are doing.

In my case, basically my challenge was to simplify. I used to read very complicated authors and sometimes I was grabbed by the story but I thought, ‘Oh my God, they are complicating so much! Why are they using one paragraph, one page? One sentence is enough.’ So, I start learning how to cut, and now this is what I do. The first version of any book of mine has three times more pages than the final one. It is like cutting your own flesh, but you need to do it.

You have said you are not a spiritual writer. Do you find ‘spirituality’ an unhelpful term?

I believe that each one of us has a spark of the divine light to manifest. It is our task here on this earth, and our human condition demands that we do it

Just because I write sometimes about my main question and it is in the spiritual world does not make me a spiritual writer. If you write about war, it does not make you a general. If you write about spies, it does not make you a spy. But when you are labelled a spiritual writer, people think: Oh, he has some answers, or he has a better connection, or… No! If there is one thing I really hate, it’s the New Age. The New Age for me is this melting pot of all types of religions created by people who do not have the courage to assume one religion.

So, I’m not a Catholic writer, I’m a writer who happens to be Catholic, uh? Sometimes I totally disagree with the Pope. I respect the missionaries of my church, of my religion, but – how can I say this in English? I want to go beyond my religion in the sense that I think spiritual insight is not only for the privileged, or Catholics or whoever: you have to discuss with people from different faiths.

In Eleven Minutes [2003], Maria says about herself: ‘Although she was very capable of writing very wise thoughts, she was quite incapable of following her own advice’ –

It is my case – sometimes. But I try to be as close as I can to my words, because mostly I write for myself. I write to… yeah, to have a better glimpse of who I am. I’ve just finished a new book and I realise, my God! these things were there and I couldn’t see them. Like when Jesus heals the blind man, he goes to the synagogue and says, ‘Hey, he healed me!’ And they say, ‘Oh, come on! He’s a fake, he’s a charlatan.’ And the man says: ‘I don’t care. I was blind but now I see.’ So, this is a little bit my case: sometimes I’m blind to myself but the answer is in my soul and all of a sudden I start seeing.

You have sold over 100 million books –

One hundred and thirty-five, to be more precise.

That’s an awful lot of people who are, surely, looking to you for more than just an expression of who you are –

I have heard this comment a lot of times. Let me tell you my impression. I have two ways to meet my readers: at my book signings and on the internet. Probably one person out of a thousand asks me what to do. At my signings, never. On Facebook or Twitter, eventually they’ll say, ‘Oh, today I’m like this…’ – but like I say to my wife, ‘Oh, today I don’t feel very enthusiastic about this,’ not because she has the ultimate answer for my life but because I feel like sharing my problems with her. My readers don’t ask me, ‘Paulo, what is the meaning of my life?’ They know I don’t have the answer.

Nonetheless, for many of them The Alchemist has been one of those books that transform one’s life or the way one sees the world. So, even if you never set out to do so, you have played a role in many people’s lives –

You never know. You never know. Did [Kahlil] Gibran, for example, who wrote The Prophet, know what role he was going to have in my life? Or William Blake? Or Henry Miller? Or Jorge Luis Borges? No.

Is there not something almost priestly, though, in the work of great writers?

Do you think that Henry Miller has that? No! No! No! There are writers who try to do this, but they are condemned to fail. I don’t read books that try to teach me this and that, because – well, I can learn for one week but then these teachings are going to disappear. Like self-help books, you know? You read them, you think, ‘OK, this will change my life’ – and one week later you have the same problems. So, when you write, you don’t write to teach, you write to learn.

And you’re never conscious who you are going to affect. I was really affected by the Beatles. Do you think that for that I should praise or blame John Lennon and Paul McCartney? No. They did not even know that I existed. But they were there and they were sharing the same things I was thinking at that very moment, and that feeling really made a difference, that I was not alone. Probably it is the same with my books. People feel that there is this writer and he feels the same things that they feel and they are not alone. But that is all.

And you’re never conscious who you are going to affect. I was really affected by the Beatles. Do you think that for that I should praise or blame John Lennon and Paul McCartney? No. They did not even know that I existed. But they were there and they were sharing the same things I was thinking at that very moment, and that feeling really made a difference, that I was not alone. Probably it is the same with my books. People feel that there is this writer and he feels the same things that they feel and they are not alone. But that is all.

Do you consider yourself a writer of magic realism? Your books are magical, but you describe The Pilgrimage and The Valkyries [1992] as ‘non-fiction’ – obviously. You couldn’t make that stuff up, really, could you?

Well, shall we talk specifically about The Valkyries? Of course it’s not 100-per-cent non-fiction, right? But the emphasis is there. So, I would not call myself a magical realist, no. I would call myself a realist who has touches of magic in his writing.

Is there a whole invisible world out there that most of us are missing?

Of course there is. Of course. Invisible and very present, you know? For example, you cannot touch love or fear or anger, uh? They’re invisible but sure they are there – and affect your life much more than the money that you have in your pocket, that is visible. The same, for me, goes for God, uh? It is not visible but it is there. And there is no need to explain, to justify – One of the few questions people ask me is: What is God? I say, ‘I don’t know. I only have my experience of God. I cannot share this, it is impossible to share it.’

But then you talk about personal messengers and guardian angels and a devil in the form of a dog that was stalking you –

Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah.

If I started talking about such things in my church, they might ask me politely to leave if the problem persisted.

I don’t think so. They’ll be very interested, very interested, because the magic moments in our lives are when the invisible world touches this visible world.

That’s why at the end of The Alchemist the boy finds an earthly treasure. A lot of people say, ‘Why did you have the boy finding a physical treasure? The journey itself was magical.’ I say: ‘Yes, but he was not searching for magic, he was searching for a treasure.’ You know? I couldn’t not put it there. The alchemy is exactly that.

If you talk about the visible manifestation of God in the world at your church, you’ll be surprised how many people there have had this experience and are just afraid to share it, because they think they’re going to be labelled as crazy, you know? People really fear to talk about these things.

The other day, as a Lenten exercise, I was walking a labyrinth on the top of a hill in silence with three other people when a sheep appeared from nowhere – I have never seen one there before – and it came right up to us, limping and baaing and baaing. It walked around and across the labyrinth for two or three minutes and then it retreated, looked at us and went over the hill. Do you think it was trying to communicate something?

Do I think? Yes. I talk about that in The Pilgrimage, when a sheep also guided me. I do believe that (as I put it in The Alchemist) we are not just separate manifestations, we are part of the same flame. We are sparks, but sparks of the same flame. I tend to see everything as a miracle.

We are sparks of one flame, but we are all individuals, aren’t we? You talk about how we must understand our difference if we are to make the difference…

Yeah, absolutely, absolutely. And this is one of the contradictions that I have to learn how to live.

I believe that the world is being created now and destroyed now. We live in eternity; we can redeem ourselves, our past, our future, with something that we do right now

Does mainstream religion hold us back by its lack of imagination or its fear? Is there a point where anyone of faith has to transcend what they have come to believe in order to enter more deeply into this real world?

Today, at least in my religion, there is a lack of belief in miracles. For example, I am a [devotee] of the Immaculate Conception and St Bernadette and so every new year’s eve my wife and I travel to Lourdes to stand in front of the grotto in the sanctuary there. The last recognised miracle in Lourdes was in the 19th century, in 1892 or – I don’t remember when. But I am positive that in 120 years a lot of miracles [have] happened but the church [has been] a bit reluctant to accept them. ‘How can we talk about this supernatural thing…?’

No! God is beyond reality and is part of reality. He is, as he defined himself to Moses. But religions today – at least, Catholicism is very reluctant to accept the supernatural aspect of God. And then we lose, in my opinion, a lot of important things. It is by accepting that you open the door. But people are opening the door, I think, more and more and more.

Try to do that in your church, Brian! You are going to be surprised.

When I was reading The Pilgrimage, I found that in one sense you made the spiritual realm very complicated – the various different exercises, all the references to the Tradition, the Knights Templar, and so on. It seemed secretive, and almost Gnostic. And yet the thrust of the book seems to be that there are no secrets.

On the first page of The Pilgrimage I dedicate the book to my guide [the Peruvian-born US anthropologist and purported shaman Carlos] Castaneda – he was very important to my generation – and I say that at the very beginning of this journey I was thinking, ‘Oh my God! There are secrets, there are, you know, orders, and I was looking to you, Castaneda, as the person who was going to reveal all these secrets.’

And then – at the very beginning of the book, uh? – I realised that this was not true. That the extraordinary bites in the common life. That to Jesus there is nothing that was hidden that is not revealed. And I do believe in that, and I live by it, uh? At the very beginning [of my pilgrimage], this was my transformation, this was my turning point: Don’t complicate, Paulo! Things are easier than you think. Just open your heart and let the light of God inside!

You talk about ‘the good fight’. Do you think we are engaged in some kind of cosmic battle, good versus evil?

Always, always, yeah, yeah. From the very beginning. But it’s interesting… How can I put this? I don’t believe in time, right? I believe that the world is being created now and destroyed now. We live in this eternity; we can redeem ourselves, our past, our future, with something that we do right now, uh? So, there is this battle, but it is proposed by God. I’m a monotheist, I can’t believe that there is another force as powerful as God, an evil force that can defeat the good force. So, this belongs in the realm of things to which I don’t have answers, and I don’t try to answer.

What I know is that in the Lord’s Prayer is written ‘Don’t lead me into temptation!’ What does it mean? It means that at the end of the day it is God who is testing us. There is a struggle, but it is the same kind of struggle that we see [when] spring is coming. I don’t think that Winter is very happy, you know? He wants to stay, but Spring says: ‘I am coming.’ There is this cycle of life that we don’t understand. [In the autumn,] you look at the trees and you say, ‘Oh my God! Nature is killing the leaves.’ No! Come on! This good versus evil, it is Nature, you know? And it is in our nature.

So, I don’t have the answers to the classic problems. I only have my attitude, and my attitude is: Respect the mystery! Don’t try to find an answer. You may give an answer that convinces a lot of people, because you have good oratory, but is it honest? Is it fair? Better to say: I don’t know. And this is my case.

So, I don’t have the answers to the classic problems. I only have my attitude, and my attitude is: Respect the mystery! Don’t try to find an answer. You may give an answer that convinces a lot of people, because you have good oratory, but is it honest? Is it fair? Better to say: I don’t know. And this is my case.

Do you think you would have ended up doing what you are doing now if you had not suffered as you did in your youth, first in a mental asylum and then at the hands of the secret police?

You are asking me: Do you believe that suffering is important? The answer is: No. Look at the life of Jesus: he spent 99 per cent of his life talking to people, travelling, having dinner, drinking – and then, in the last three days, ah! there is the cross, and he’s dead. Did he suffer for…? Well, he had his inner conflicts, all right? Let’s not talk about them, uh? He even felt abandoned. But, but… Suffering is not important. Do you think it is?

I had to ‘suffer’ because it was in front of me. In fact, when I look back I did not suffer. You know? It was just part of my journey. And that brought me here. What if I had not suffered these things, would I be the same successful writer? Probably.

But would you be the same person you are now?

Yeah, I don’t know. Really I don’t know.

There is a tension between dying to yourself and taking up your cross and at the same time becoming the person you were created to be. How do we live with that?

Well, that tension is what guides me throughout my life. But I never forget that Jesus’ first miracle was not ‘I’m going to heal this sick person’ or ‘I’m going to exorcise this demon.’ It was very mundane, and it was not politically correct: ‘Ah, there’s no wine!’ ‘Come on, man! It’s not my time yet.’ ‘But, my son, there is no wine – and we are celebrating.’ So, Jesus turned water into wine. And this is what makes him human, I think, these moments of doubt and anger and joy, and his inner tension.

How do you know when you have experienced true alchemy? How do you know you’re not just making it up?

You never know. You never know. Again, it is an act of faith. You have to ask for guidance from God: Inspire me! When Jesus went up to Simon called Peter and his brother, Andrew, and said, ‘Stop fishing, uh? Follow me!’, they didn’t say, ‘To where? What are you going to do?’ No. ‘At once they left their nets and followed him.’ Either you follow or you don’t. And it is there that your faith is tested.

Jesus says, ‘Follow me,’ not ‘Follow your personal destiny.’

Well, then again, my personal destiny is to follow him. And the personal destiny of Simon Peter and Andrew. And your destiny, Brian, is to follow him. The destiny of my neighbour may be eventually not to follow him – but this does not make him worse than I. You know? If he does good deeds, he is as worthy as I am.

As you grow older, do you find it to be the case that the further you go, the less you really know?

Well, I’ve been living with the mystery, or the questions, since I did the pilgrimage and realised that I don’t need the answers, I only need the religion and the respect.

Do you do your spiritual exercises every day?

I was educated in a Jesuit school, Brian. One of the first things you learn is to do the exercises by St Ignatius, and you get used to doing them every day. I cannot just say, ‘Oh, I am not going to do that today.’

But you serve God in many different ways. Many times you are serving, you don’t know you are.

Can you still shatter glass without touching it?

I can, but it is useless. Let me use my force to do something much more important!

Thank you for the opportunity to talk to you.

My pleasure. May God bless you. Bless me, Brian!

This edit was originally published in the June 2010 issue of Third Way.

To make sure you hear of future interviews in this series, follow High Profiles on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

| ⇑1 | Published in Portuguese in 1987 as O Diário de Um Mago, and originally published in English, in the United States in 1992, as The Diary of a Magus |

|---|

To find out more about the agenda behind our interviews, read our manifesto. To access our archive of more than 260 interviews, see the full list.

Biography

Paulo Coelho was born in 1947 in Rio de Janeiro, where he attended St Ignatius College for five years.

In 1965-67, as he tried to establish himself as a poet, a journalist, an actor and a playwright, his parents committed him three times to a mental asylum. He embraced the hippie drug culture and the occult – and ultimately Satanism – and travelled extensively.

In 1972, he began writing lyrics, most notably for the rock singer and songwriter Raul Seixas, with whom he enjoyed phenomenal success with the albums Gita (1974) and Há Dez Mil Anos Atrás (1976). His first book, on theatre in education, came out in 1973.

In 1974, he was interrogated about his ‘subversive activities’ by agents of Brazil’s military government.

From 1974 to 1979, he worked as an executive in the recording divisions of Philips and, briefly, CBS. In 1982, he launched a publishing house, Shogun.

In 1986, after walking over 400 miles of the pilgrims’ way to Santiago de Compostela, he returned to the Catholicism of his childhood. His first major book, now known as The Pilgrimage, was published the next year.

It was followed by The Alchemist (1988), which, after failing initially, went on to become one of the best-selling books in history, published in 68 languages.

His subsequent books include Brida (1990), The Valkyries (1992), By the River Piedra I Sat Down and Wept (1994), The Fifth Mountain (1996), Manual of the Warrior of Light (1997), Veronika Decides to Die (1998), The Devil and Miss Prym (2000), Eleven Minutes (2003), The Zahir (2005), The Witch of Portobello (2006), The Winner Stands Alone (2009) and the anthology Inspirations (2010).

In 1996, he founded the Paulo Coelho Institute, which gives assistance to the poor people of Rio.

Among the many international honours he has been given, he received the prestigious Crystal Award from the World Economic Forum in Davos in 1999 and was made a Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur in 2000 and a UN Messenger of Peace in 2007.

His partner since 1980 has been the Brazilian artist Christina Oiticica, with whom he lives in Rio and a village close to Lourdes. They have no children.

Up-to-date as at 1 April 2010