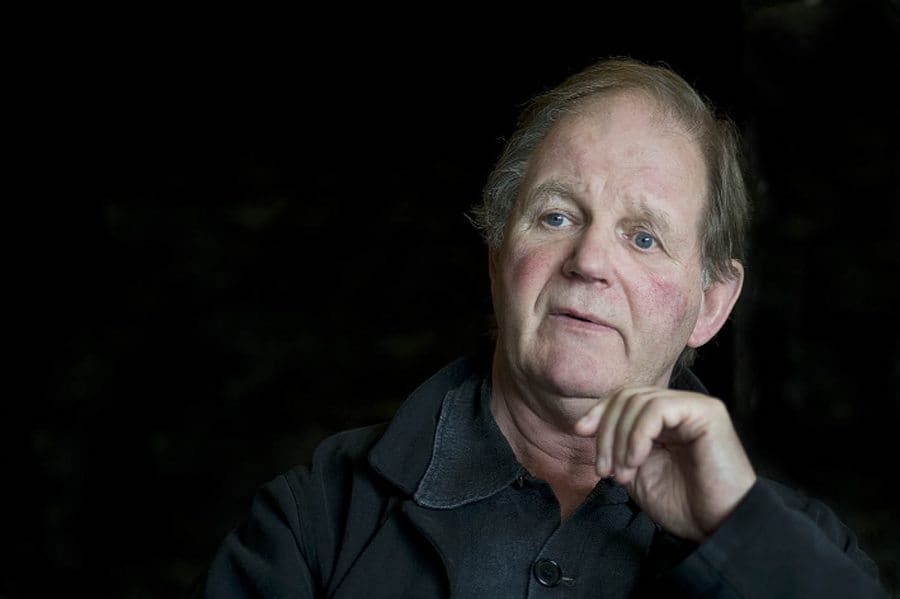

Michael Morpurgo

is a nailed-on national treasure. Huw Spanner met the prolific children’s author and former Children’s Laureate, the creator of War Horse and Private Peaceful, on 18 April 2013 in his local, the Duke of York in Iddesleigh.

Photography: Andrew Firth

I’ve just read Maggie Fergusson’s fine biography of you1Michael Morpurgo: War child to War Horse (Fourth Estate, 2012) – I don’t know if you were happy with it –

Yes, very. It’s a very honest book. It told me a lot about myself I didn’t want to know and maybe didn’t think anyone else would ever find out.

She says you’re a complex man and quotes your brother and a close friend at school to the effect that you’re an enigma, perhaps even to yourself.

I think that’s about right. I think I look inside myself too much and still can’t work it out.

You’re an introspective man?

Yes. Like a lot of writers, I spend a lot of time alone, so perforce I’m looking into myself as much as I’m looking out. I used not to be, when I was a teacher, where you’re performing… The lovely thing about performing is, you leave all the other stuff behind. Actually, performing is what I love doing most now. It’s my way of relaxing.

Why do you so love performing?

My mother and my father were both actors and I think that deep down I probably suppressed quite a lot of that in myself earlier on, because it didn’t seem to me to be a career that was open to me. But the older I get now, the more I love telling stories. And singing. I’m now doing a series of concerts around War Horse and Private Peaceful and my own version of the Nativity, On Angel Wings. I’m doing it with a wonderful folk group who sing with a real passion – and I get to sing, in front of sometimes a thousand people. I haven’t got a brilliant voice, but I simply love making music, and losing myself in the performance of others.

In Alan Bennett’s play The History Boys, there is a teacher who says: ‘All we’re here for is to pass it on.’ I think that’s the most wonderful thing to say, and it’s true: that is what you’re here for. You pass on what you love. It’s what my mother did to me with her poems and her stories. It’s what my old professor did at King’s College London, sitting on his desk and reading us [Sir] Gawain and the Green Knight. He was simply passing on what he loved to me, as if I were three – and it was the child in him [who was] reading it. And it’s what I now do, not just to kids but to all sorts of people.

In The History Boys, there is a teacher who says: ‘All we’re here for is to pass it on.’ You pass on what you love. And that’s what I do – not just to kids but to all sorts of people

Originally, you’d set your heart on going into the Army. How come that was your first choice of career?

I was probably looking to measure myself against the people I admired most – and certainly my two uncles. One of them, who died in the war when he was 21, had it all, really: he was a Shakespearean actor, trained at Rada, and he was extraordinarily good-looking. The other was a pacifist who was going to spend the war, I don’t know, digging up potatoes in Lincolnshire; but then his brother was killed and so he changed his mind and joined up and became a [secret] agent in France and had the most extraordinary experiences. I was brought up on the stories of these people.

It also had a lot to do with my stepfather, who had been a major in the Royal Artillery. He was a very conventional man, I think, in the sense that he wanted a career for his children and his stepchildren that was always identifiably moving towards success, and I think he saw success in terms of ranks.

And then I found myself at a very conventional public school, in Canterbury, where I wanted to excel, but I didn’t excel academically. I excelled on the rugby field and the other thing I found I could do was to persuade people to do what I wanted them to do.

What was that in you? Charisma, or…?

Probably something pretty horrible, I don’t know – I’d rather not go into it! It was known as ‘leadership’ in those days, I suppose, and at my kind of school you got Brownie points for being like that. Nowadays, you’d be regarded as a bit of a manipulative so-and-so.

Anyway, I went to Sandhurst on an Army scholarship and, you know, I was going to be a field marshal by the time I was 22. Everyone thought I was just…

Do you think now you would have cut it as a soldier?

Oh yes, I think I would have made a success of it.

So, why did you quit after only a year?

I met Clare, this lady who was to be my wife, and she was the first person to ask me: ‘Sorry, what are you doing this for?’ And the more I thought about it, the more I began to question it.

And then there came a road-to-Damascus moment, I suppose. We were on a three-day exercise, I remember, out on some blasted heath in the winter snow. The ‘enemy’ were the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, who didn’t like the English and hated all officer cadets with a passion, and they were singing ribald songs to us across no-man’s-land, telling us what they would do if they caught us. I knew it was a game, but it sort of wasn’t a game and it was quite scary.

And I remember sitting in this trench in the middle of the night and thinking of Christmas 1914 and the carols going back and forth between the German and the British trenches and then the soldiers meeting in the middle the next day and attempting to make peace,2See bit.ly/ctuDl. and it occurred to me that actually that is what I would like to be doing.

After that, Clare and I talked more and more about it; and then fate lent a hand and she became pregnant –

You were very young, weren’t you?

I was 19 when I got married, in June 1963 – and she was only a couple of years older. It’s no wonder neither set of parents was exactly thrilled. We thought it was great!

Whatever I was teaching, I did it with a fervour and I found children responded. If I was reading a story, I found they listened because I gave it everything. The thing with children is, you have to mean it

So, then you sort of stumbled into teaching?

Very much stumbled, yes. I got into King’s College London to read for a degree – I wasn’t that interested in the course, didn’t really apply myself – to be honest, I was treading water, wondering which way the current was going to take me. And in the end it took me into teaching, because I loved my children – by this time I had two of them – and I felt connected to children in quite a strong way, and to my own childhood.

You didn’t have any training. Were you a natural teacher?

I think I probably was, yes. I found that whatever I was doing with children, I could perform it. Whatever I was teaching, I did it with a fervour and I found that they responded. If I was reading a story, I found they listened because I gave it everything. I think I understood very quickly that the thing with children is, you have to mean it. Whatever school I taught at, I felt that many children were already alienated because they’d had adults standing in front of them trying to get them to learn something they weren’t that interested in themselves.

In a letter you wrote to Clare after you got engaged, you spoke of ‘doing our utmost … to fulfil [our] vocation’. Where had you got that sense that there was something you ought to be doing with your life?

I think that came from my mother’s side, really. She came from a family of very strong Christian Socialists – they were great friends with George Bernard Shaw. Her mother was deeply Christian, a follower of Jesus in every way, and her father was a preacher. When you went to their house, there were Piero della Francesca pictures of the risen Christ in the dining room and you said grace before every meal.

My mother had ‘disgraced herself’, in the sense that she had divorced my father just after the war – my stepfather had appeared on the scene and my father came back from the war to find his wife (if you like) occupied. (I hardly knew my father – I’d probably only met him on a couple of occasions.) But she still had not left her upbringing behind her and, I’m quite sure, she passed on to me this feeling that you are on this earth to do something useful with your life, to make a difference if you can. Being frivolous is not what life is about.

And there was another reason, and that is that Clare had had a Quaker upbringing. She was the daughter of Allen Lane, the man who started Penguin Books, who was one of those rare people who made money from doing good – bringing literature to millions and millions of people. And there was in that family a sense that that was a fine thing to have done. It was an extraordinary family, really, because they were very wealthy but no one admired money. At all. And Clare least of all.

You were quite devout as a teenager, I believe, but my impression is that now you are not that impressed with organised religion but you have a sense of Providence, perhaps – or maybe it’s just fate – and you also have some regard for Jesus as a person. Is that correct?

I have more than just a regard for Jesus – I see him as one of the wisest people that ever lived. I don’t actually care too much about the miraculous side of the Christian story – I love the stories, mind you – but it is the genius of the man, really, I suppose, his understanding of human nature, that seems to me to be so persuasive.

I mean, I grew up under the tower of Canterbury Cathedral, I sang in the choir there –

As school captain, you had your own key to the cathedral!

Yes, I did. I’m very connected to church architecture, church music – all of that, I think, to me is a wonderful guide to living. I have a hope of eternal life, but I don’t have a rock solid faith in it. I think sometimes the older I get, the more I want to; but I find it difficult.

And then I have seen what organised religion has done in the world, the great benefits it’s spread about the world – one of my ancestors is Charles Wesley – but also the immense harm it’s done and is still doing; and that alarms me. I know perfectly well it’s absolutely not what Jesus had in mind. The older I get, the more absurd I find it that people who follow him spend their time squabbling about which liturgy they should use – and the wealth and the power the Church has accrued I find – and I’m sure he would have found – rather displeasing. Well, we know what he did when he found the money changers in the Temple.

And then I have seen what organised religion has done in the world, the great benefits it’s spread about the world – one of my ancestors is Charles Wesley – but also the immense harm it’s done and is still doing; and that alarms me. I know perfectly well it’s absolutely not what Jesus had in mind. The older I get, the more absurd I find it that people who follow him spend their time squabbling about which liturgy they should use – and the wealth and the power the Church has accrued I find – and I’m sure he would have found – rather displeasing. Well, we know what he did when he found the money changers in the Temple.

Anyway, I suppose what I’m saying is that I am an aspiring believer, and always have been. When I meet someone of faith, provided they’re not bigoted, I am very envious. I admire the fact that they have arrived at a kind of clarity of thinking that I don’t seem to be able to. I feel a lot of guilt about that.

In 1975, you moved from Kent to this quite remote part of Devon to set up Farms for City Children.3farmsforcitychildren.org Am I right that that was more Clare’s idea than yours?

Absolutely, yes. Both of us were teachers and we had arrived at the conclusion that the system itself seemed to be perpetuating success for those children who were already going to succeed (because they came from those kind of homes) and failure and alienation for [the rest] – and wasn’t doing much more than that. And the more I listened to my fellow teachers, the more I realised that this needed changing.

So, we thought about what it was that had changed our lives when we were little; and Clare said that really the most important time of her life was not in a school, it was coming here [to Iddesleigh], staying in this pub, and just going on walks out into the countryside, meeting farmers and digging potatoes and grooming horses and feeding calves and walking through fields and picking up lizards in the graveyard and… That kind of thing she adored – she said it is what made her what she is. And we could tell from the children we’d taught that they were suffering massively from a poverty of that kind of enriching experience.

So, we did some research and everyone we talked to in education departments or departments of psychology said the same thing: If you get children young enough – the Jesuits knew this – you can transform their attitude to themselves. If you give a child an opportunity to feel that they belong, that they can make a contribution, that they’re important, their self-worth grows, and with that comes the confidence to handle themselves and the world around them.

And then we got lucky – we’ve been hugely lucky! As Nelson Mandela said, none of us ever gets anywhere without the right people being there at the right moment to kind of give you a hand on. And at that particular moment in our lives, Clare’s daddy died and left us some money. We bought this big house down the road and made a partnership with a farmer living next door and invited 35, 40 kids down at a time, with their teachers, from London, Bristol, Birmingham, Manchester… We had eight schools in the first year, and we’ve been full ever since – and now have two other farms. We had very little sense of what it was all going to involve, we knew precious little about farming – it was crazy! But I’m really glad we did it. It turned out to be the most enriching thing we’ve ever done – forget the children, it was fantastic for us! We know from the children that it’s also worked wonderfully for many of them.

There is something much more important we should be doing with education, which is to do with the opening of eyes and ears to the world around us and the keeping open of minds

And to me as a writer, of course, it gave something I’d never had before. I had started writing before this, rather superficial little stories based on my experiences as a young teacher and father. They were OK, but I had never before had an experience of life as intense as what I was getting here. I’d never got to know a community as well, in all its complexity, as I did when we settled here. And so, of course, the stories came as well.

In what ways has your sense of what you are giving to the children deepened over the last four decades?

When I was first teaching, I was teaching for results. (I think a lot of teachers fall into this trap, and it’s a trap that people like [Michael] Gove4Interviewed for High Profile in March 2010 want us to fall into.) I wanted my children to get on. I wanted them to pass their examinations, to be good at spelling and punctuation – and don’t get me wrong: these things are not unimportant! But I was thinking of education very much as a series of achievements, in which I could help them by inspiring them or cajoling them or whatever.

What I discovered here was that there is something much more important that we should be doing with education, which is to do with the opening of eyes and ears to the world around us, the keeping open of minds and the stimulation of the imagination. What there was here was wonder, was amazement, and it was felt physically, it was felt emotionally, it was felt intellectually. For seven days, the children were coping with the things we all, essentially, have to cope with: birth and death.

We would bring the children up to this village and take them to the church and say: ‘This place was built, 600 years ago, by people who worked in the fields like you’ve just been working. This is where they came to be baptised, this is where they came to be married, and in a minute I’ll show you where they’re buried.’ What we were doing was trying to put them in touch with the fact that they’re part of this on-rolling, ever-changing passing of seasons and years and generations. I don’t think that’s a concept that they’d come across before, and I think it’s really important.

And, besides, every single one of them went home with some sense of achievement – not just the ones who achieve at school with the punctuation and the spelling.

We need to get onto your writing.

I don’t know why – this is much more important. This is, by a long way, my best story! But I’m quite happy to talk about the other rubbish…

It strikes me that the authors you loved as a child – Robert Louis Stevenson, G A Henty – aimed primarily to excite and entertain their readers, whereas your writing seems to me to major on emotion. Your chapters typically end not with a cliffhanger but with an emotional hit.

Yes.

Why is that? Are you an emotional man?

I’m very emotional.

What I admire in other writers very often is what I know I haven’t got. So, these are the people I admire, not the people I wanted to emulate.

Would I be right to think that your writing has a strong element of didacticism in it – that there are lessons you are trying to communicate? In Private Peaceful, for example, there is stuff about social injustice, stuff about war, stuff about tolerance, kindness and self-sacrifice.

For me, the child in me is my soul. And for me the soul of us is what needs sustaining, and sometimes healing, right the way through our education

No, you wouldn’t be right. I suppose it might seem like that because there is in each book a fairly evident moral position. That’s certainly true. When I write about war, I tend to concentrate on what Wilfred Owen called ‘the pity’ of it, and the hope for peace, because I believe in it.

But I think it’s also true that in each of my books I am trying to work things out – I haven’t come to conclusions. For instance, it’s very easy to [condemn] wars that you know were absurd, like the First World War; but it is much harder with the war against Hitler or the Falklands war – then how pacifist are you, Michael Morpurgo? I am still asking myself those questions.

I think writers for children, just as writers for adults do, have to write about what interests them, what they themselves care about. And I think it’s important to leave questions in children’s minds, not to tell them how it is but to tell them how you find it, and how the people in the story find it, and then leave things as open as you possibly can.

You’ve said that you don’t really write with your readers in mind but ‘for the child inside myself that I still partly am’…

Yep.

And Jesus said that unless we become like little children, we will never see the kingdom of heaven –5Matthew 18:3

Absolutely.

So, what is the difference between being childlike and being childish? And what is it right to hold on to from childhood and what are the things we should ‘put away’, as the apostle Paul put it?61 Corinthians 13:11

One of the worst things St Paul ever said. I’ll have to sort him out when I get up there!

The word ‘childish’ has simply become this awful word that we use when we want to put someone down as being immature. It seems to denigrate all those things that go with childhood: wide-eyed wonder, a sense of fun, even a sense of irresponsibility. It really is a dreadful word. For me, the child in me is my soul. If you lose that, I think you lose your soul. And I think that one of the worst things about growing older in our society is, there seems to be – and I’m not joking about this, I do think St Paul has something to answer for – an assumption that you have to grow away from being a child in order to become an adult, instead of the child in you becoming part of the adult that you become.

And that leads us to think that somehow children are not so important. The number of women who come up to me at book signings and I say, ‘What do you do?’ and they say, ‘Oh, I’m just a mother.’ And you think: ‘What on earth…! You’re doing the most important job in this world and you use that ghastly word “just”!’ Why? Because there is this thing that if you deal with children – particularly small children – somehow you don’t have status in society.

And it goes right through our education system. We all know that it is professors at Oxford and Cambridge who have the status. Why? They’re teaching these adult people with great intellects and that’s grand. And it is grand, but it’s at the expense of the nursery teacher.

It’s the same with books. I find it utterly extraordinary that the people who edit the literary pages in the newspapers so despise the world of children’s literature, if it gets on the back page you’re lucky! Instead of accepting that, actually, if you read Judith Kerr’s The Tiger Who Came to Tea to a kid of three and that kid lights up with the glow of it and the fun of it and wants to hear it again, that’s the child who’s going to be sitting in the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in years to come watching The Tempest, that’s the child who’s going to be writing the new stories. It’s such a strange gap we’ve created between our adult selves and our child selves, and it’s done irreparable damage, I think.

I’ve just talked at a Montessori conference in Amsterdam, to teachers from 32 different countries, and it is the same the world over: they’re not taken seriously – and they’re doing this extraordinary job of bringing children to some connection with the world about them and their own self-confidence. It’s so, so important! And for me that is because the soul of us is what needs sustaining, and sometimes healing, right the way through our education. You mustn’t miss out on the early years. Once that’s done, the professors can work on that material and the eyes and the ears will still be wide open.

I’ve just talked at a Montessori conference in Amsterdam, to teachers from 32 different countries, and it is the same the world over: they’re not taken seriously – and they’re doing this extraordinary job of bringing children to some connection with the world about them and their own self-confidence. It’s so, so important! And for me that is because the soul of us is what needs sustaining, and sometimes healing, right the way through our education. You mustn’t miss out on the early years. Once that’s done, the professors can work on that material and the eyes and the ears will still be wide open.

Do you see lessons for us in the way young animals grow up on the farm?

It seems to me that what’s wonderful about the best of early education is that you allow children to grow up like young pups: they spend a lot of time cavorting and running about and exploring and finding out the world for themselves and finding out their parameters and understanding what risk is, all those things you have to find out for yourself; and unless you’re given the space to do it – and the space, I have to say, to sit and dream – then children are not being properly educated.

One of the worst things at the moment is that we’re trying to urge children into this structured [world of] ‘the learning process’ and being tested and examined far, far too early. We think somehow we have to hurry them towards that so that the product at the end of the day will be somehow superior to a South Korean worker or something. That’s the sort of level we’ve got [to]. For me, the growing of a child is critically important, and the slowness of it is critically important – allowing each child to develop at their own pace, in the way that is best for them. The best kind of education does that.

You’ve observed that adults come out of performances of War Horse in tears but children generally don’t. Are adults more sensitive than children, or are children more resilient?

It’s been wonderful to witness how different generations come to the same story, bringing their life’s experience with [them], whatever it is. A kid of eight thinks: ‘I care what happens to that horse, I really want him to meet up with his friend again. That’s all that matters to me. And isn’t that war thing horrible?’ That’s the level at which they respond to it – and that’s fine.

The parents are more connected, I suppose, to the war that goes on today, and what it does to people, and they also have some sense of what the horse represents – the innocent victim – and they have the imagination to live through the suffering of the horse and the boy.

And then you get my generation, who have not necessarily lived through war but know people who have, know how ghastly human beings can be to each other.

But what’s really wonderful is that in all three cases there is the imperative of hope. After one performance, a woman came up to me and said: ‘This is the greatest anthem to peace I’ve ever seen.’ And I think that resonates enormously with people: this longing for peace. A worldwide longing for peace. And what’s really wonderful is, it’s going to open in Berlin in September. I love that. This is very much a show about reconciliation and I feel that it’s found its moment.

You’re 70 this year, and in your writing you have gone back 100 years now. Our society has changed hugely in that time. Do you think that on the whole it’s got better, or worse? Or is it one step forward, one step back?

I think it is one step forward, one step back. In all sorts of ways, of course, it’s got massively better – you know, we live longer, most of us live happier, there is much less abject poverty than there was – though I have to say the gulf between rich and poor is about the same as it was 100 years ago, I should think. The downside is the destruction we’re doing to our planet in the process of making ourselves so comfortable.

But, you know, children are by and large becoming better educated, and I think that’s very positive. I do believe very firmly that it is through education, and literature – and thinking – that we will win through as a species. But we are making massive mistakes on the way.

Where do you find most hope, then?

Principally in children. In 2009, I wrote a little story – a parable, if you like – called The Kites are Flying!, about children in Israel and Palestine getting to know each other by flying kites over the Wall. I suppose it’s a statement of faith that the only hope we have is our hope in the next generation. If we don’t get that right, we will simply go from bad to worse. But, yeah, I’m hopeful.

This edit was originally published in the June 2013 issue of Third Way.

To make sure you hear of future interviews in this series, follow High Profiles on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

| ⇑1 | Michael Morpurgo: War child to War Horse (Fourth Estate, 2012) |

|---|---|

| ⇑2 | See bit.ly/ctuDl. |

| ⇑3 | farmsforcitychildren.org |

| ⇑4 | Interviewed for High Profile in March 2010 |

| ⇑5 | Matthew 18:3 |

| ⇑6 | 1 Corinthians 13:11 |

To find out more about the agenda behind our interviews, read our manifesto. To access our archive of more than 260 interviews, see the full list.

Biography

Michael Morpurgo was born in St Albans in 1943 and was educated at The King’s School, Canterbury, where in his final year he was Captain of School.

In 1962, after two terms teaching at a prep school in Sussex, he went to Sandhurst, but quit after a year. He then studied French, English and philosophy at King’s College London, graduating with a third.

From 1967 to ’74, he taught at a succession of junior schools, in Hampshire, Cambridgeshire and Kent.

In 1975, he and his wife bought Nethercott Farm in Devon and set up the charity Farms for City Children, which now also runs a farm in Pembrokeshire (since 1990) and one in Gloucestershire (since 1997). So far, they have welcomed some 120,000 children.

His first book, It Never Rained (1974), has to date been followed by more than 120 others – notably, All Around the Year (1979) with Ted Hughes; War Horse (1982), which was runner-up for the Whitbread Book Award; Why the Whales Came (1985); Waiting for Anya (1990), shortlisted for the Carnegie Medal; King of the Cloud Forests (1993), which won the Prix Sorcières; Arthur, High King of Britain (1994), shortlisted for the Carnegie Medal; The Wreck of the Zanzibar (1995), which won the Whitbread prize; The Butterfly Lion (1996), which won the Smarties Prize; Kensuke’s Kingdom (1999), which won the Red House prize and the Prix Sorcières; Private Peaceful (2003), which won the Red House and Blue Peter prizes among others; Alone on a Wide, Wide Sea (2006); The Mozart Question (2007); This Morning I Met a Whale (2008); Shadow (2010); and A Medal for Leroy (2012).

War Horse was adapted for the stage by the National Theatre in 2007 and is now running in the West End and (since 2011) on Broadway. In 2011, it was turned into a major film directed by Steven Spielberg. In 2012, Private Peaceful was staged at the Theatre Royal Haymarket, London and also filmed by Pat O’Connor.

From 2003 to ’05, Morpurgo served as Britain’s third Children’s Laureate (a role he originally conceived).

He was made an MBE in 1999 (for services to youth), a Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres in 2004 and an OBE in 2006 (for services to literature).

He has been married since 1963 and has three children and seven grandchildren.

Up-to-date as at 31 March 2013