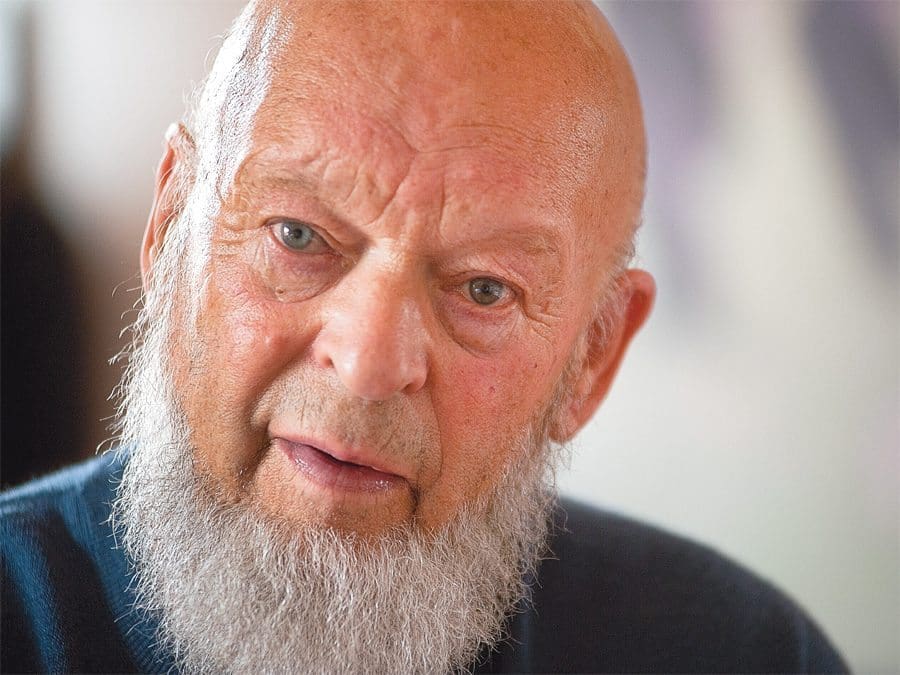

Michael Eavis

was recently identified in Time as one of the most influential people in the world. Steve Turner joined the co-founder, chief executive and host of the Glastonbury Festival for a chinwag at the office on 22 July 2015.

Photography: Andrew Firth

Your first name is Athelstan. When did you decide you’d rather be called something else?

My mother was very keen to name me after her grandfather for some reason, so I was lumbered with it; but when I went to school, she said: ‘It’s embarrassing for you, so I’ll call you Michael.’ I was a bit shy, you see.

Where did you go to school?

I went to the village school until I was nine and then I went to Wells Cathedral School. My mother was very keen that we shouldn’t just be ordinary farming types – she was a headmistress and a bit snobby, really. She didn’t like the local dialect and all that, so I had to go to a posh school. I had to board to get the full treatment. I wasn’t mad crazy on the idea of boarding, I must say – I was away from the farm for five years.

Was it a disappointment to your parents when you left school at 15?

My father wanted me to do the farming but my mother was more ambitious. She had a very handsome cousin who was a commander in the Australian navy and she wanted me to follow him, so I went off to train to be a midshipman in the Merchant Navy; and then I went to sea, with the Union-Castle Line.

The problem was, my father died when I was 19, so that whole great plan of my mother didn’t really work because then she wanted me home, you see. I was then called up for National Service [and I ended up] in the coalmines. I would go down the mine by day and milk the cows at night. That allowed me to keep the farm going, which is what I really wanted to do.

What is the joy in farming?

There’s not much joy. I mean, it’s really hard work, isn’t it? I was milking twice a day for seven days a week and down the mines for five days and I did that for two years. I managed to save the farm from being sold, but it was real graft.

I learnt a lot about politics and things in the mines – it was a good education for me, actually. I joined the mineworkers’ union and I got to like the people.

Do you enjoy farming now?

Yeah, because I can afford to do it properly. I have five people milking for me now and it’s a much bigger herd.

Nothing could be more down to earth than farming and nothing more glamorous than rock music. Does glamour appeal to you?

I had a Methodist upbringing, with three or four ministers in my family. I know they were a bit old-fashioned and a bit quaint, but they were sound, d’you know what I mean?

I think the glamour of my previous life probably comes into the music somewhere. When I was at sea on the Union-Castle liners, I was on the bridge, with a nice uniform and nice girls hanging around and all that sort of thing; and to leave all that to come home to a backwoods farm – I think the contrast is probably what led me into the festival. I needed a little bit of that glamour.

How did you first get into pop music?

I just used to listen to Radio Luxembourg, and the Top Twenty on Sunday evenings. I was into Bill Haley and that kind of thing – I was addicted to music when I was very young. My parents thought I’d gone barmy! My brother was playing the violin and doing classical music.

Did you play an instrument yourself?

Not really. I had to learn the recorder at school.

When I came back [from the sea] in 1954, I used to pipe music through to the milking parlour – it was only me and the cows. I wired a speaker into the collar of a nine-inch sewer pipe. It was a very primitive system but it worked pretty well and it kept me going, really, through all the grim years.

What was the genesis of the festival?

I went to the Bath [Festival of Blues and Progressive Music in 1969] and I thought: ‘This is for me!’ There was an amazing display of talent – all the best bands in the world were there.1Most notably, Fleetwood Mac, John Mayall, Ten Years After, Led Zeppelin, The Nice and Chicken Shack It was a very powerful message.

In what way was it a message?

Well, that there was something else going on out there that I was not part of.

And you wanted to be a part of it?

I needed to be a part of it, yeah.

The first festival you held on Worthy Farm, in 1970, was called ‘the Pilton Pop, Folk and Blues Festival’.2See bit.ly/1IzSvCP. Why did you decide to call it ‘Glastonbury’ thereafter?

In 1971, [the ‘upper-crust hippie’3ind.pn/1MRvMIH] Arabella Churchill and [her friend] Andrew Kerr turned up at the farm to put on a free festival and they introduced me to John Michell, who had just written a book called The View over Atlantis.4Ballantine Books, 1969 He said that Glastonbury was the New Jerusalem and wanted me to change the name of the festival.

Glastonbury had always been a centre for us anyway in Pilton: it’s only six miles away, so we naturally gravitated [there] – and my grandfather retired [there]. So, mentally and emotionally it was all about Glastonbury.

Were you impressed by the theories Michell propagated about ley lines and so on?

No, not really. I thought it was interesting stuff and they were nice people and they were good fun; but it didn’t really make a lot of sense to me and I thought they were slightly off their heads anyway. All of these people were smoking dope and doing acid and stuff and it was slightly scary, really. I wasn’t very comfortable with all that happening at the farm, actually.

I had a Methodist upbringing, with my father being a preacher and having three or four ministers in my family. I know they were a bit old-fashioned and a bit quaint, but they were sound, d’you know what I mean? So, that stuff made a lot more sense to me – and there was a morality to it. [The historian] E P Thompson, who had been a Methodist preacher at one time –

He was the author of The Making of the English Working Class [1963], is that right?

He was the author of The Making of the English Working Class [1963], is that right?

Yeah, that’s right. Well done! He was a great moral figure and he spoke from the Pyramid [Stage at Glastonbury] with passion about peace and social ecology and workers’ rights and all that sort of thing. He was such a good chap, and an incredible speaker.

I suppose CND came in at that point. [My daughter] Emily was born in 1979 and we were concerned about cruise missiles coming to Newbury and so we got involved at Greenham Common. That was of a lot more interest to me than all the John Michell stuff. He was a lovely bloke, though.

Did you never rebel against your Methodist background, even in the Sixties?

No, not at all. I never got carried away with all that. I kept going to chapel and it was a grounding thing. There was something there that was familiar and very safe.

You can’t remember a period when you thought, ‘Stuff that! I’m going in a new direction’?

No. I wanted to hang on to all that tradition; I wasn’t going to leave anything behind. It was important for me to be grounded, and I also was building the farm up. My socialism and the peace group all linked in with my Methodism. Bob Dylan and all that lot were singing anti-war songs in the late Sixties, and then there was Woodstock and all sorts of lovely people writing fantastic songs about peace and love and things, and that gelled with my history.

In one interview, you said that it doesn’t matter to you whether or not God exists –

I’m not really bothered about that. Or, I don’t know if that’s important to me or not. I’m more interested in leading a loving life, you know, and being generous in spirit to people that work for me. There has to be some fundamental belief in some sort of God, I think, but it’s not something I can easily identify with.

Do you pray?

Not really, no.

Do you read the Bible?

No.

Isn’t that a funny sort of Methodism?

I just sing hymns. I love the hymns! And the romantic idea of there being a Creator, a God, that created all of these lovely things – children and falling in love and all that whole thing – and caring about people and showing that care in a very real way so that my upbringing makes a difference to what I do every day.

But John Wesley’s moral principles were very much based on his belief that we all bear the image of God.

No doubt about that, yeah.

So you do believe that?

Well, we’re all part of God. I mean, we’re the end result of all that evolution, aren’t we? Here we are, you and I today, and we are the end result of that creation. And so I think we’ve all got God in us, basically.

We’ve got God in us or we’re part of God? Which is it?

We’ve got a little bit of God in all of us. We’re all playing God, really, aren’t we? We’re all trying to do things for the benefit of the whole world, you know – trying to improve things, through politics or music or poetry or whatever it is.

I love the romantic idea of there being a Creator, a God, that created all of these lovely things – children and falling in love and all that whole thing

How come you didn’t become a preacher like your father?

I do talk a lot! I’ve never really preached, and I don’t really know what I’d say, actually, to be honest with you. But I speak somewhere every week, about my life or the festival.

Have you ever been to the Greenbelt Festival?

Never been, no.

What do you think of festivals with a religious ethos?

It’s a bit too Cliff Richard for my liking, if you know what I mean!

Have you ever invited Cliff to Glastonbury?

No, no, no. Actually, I met him here at the Abbey once and I did ask him – and he declined! He said he didn’t think it was his cup of tea. And he is quite right, really: it’s not his cup of tea.

Do you personally choose the acts?

Well, I’ve got 12 other people – including my daughter and her husband – and they’re all booking things for their particular areas. I’m choosing as well; but I’m not doing it all like I used to. I’d like to think I’ve got a say on the headliners. I generally get my own way in the end.

Do you just choose things you want to hear?

Well, things I like, really. It’s very self-indulgent!

Nobody else in the world has had so many rock legends come and play in their back garden, have they?

They all want to come now. Within two days of this year’s festival ending, at half past eight in the morning, I had an agent for three major, major bands phone and ask if they could headline in 2017. Isn’t that incredible?

Have you had people beg you to book them?

Not begging as such, but they can be very persuasive!

In one interview, you said there were 30 acts in the world that could pull a crowd of 60,000 or more and only two of them hadn’t played at Glastonbury…

Only one now!

Who is that?

Fleetwood Mac.

I’d like to get Mark Knopfler to play, obviously, but he doesn’t like playing to big crowds.

Who do you listen to at home?

Mainly Van Morrison. Neil Young. Elvis Presley still. Van Morrison is my favourite, really.

We’ve managed to create a festival where almost 200,000 people all get on with each other – you know, all mixed races, all mixed-sex. There is no nastiness anywhere. None. Isn’t that extraordinary?

Who have you had and it’s been like a dream come true?

John Martyn [in 1979] was one of the best moments.

Was he a big hero of yours?

Well, I wouldn’t… I didn’t like him as a person. He used to drink a lot and he was always difficult. He said, ‘Why don’t you treat me like a rock star?’ and I said, ‘You’re not a rock star. Sorry! You’re a very good folk singer.’ He was a bit of a nightmare, really. But he was brilliant. His music was really, really moving. Really moving.

Has there been anyone who has really disappointed you?

They don’t always come up trumps. No way, no. I can’t mention any names, really.

Do you ever perform yourself?

I sang three times this year! I sang on the Avalon stage, and the Moody Blues invited me to join them for a song called ‘Question’ – a wonderful song, that is5See bit.ly/1SVoW4m. – and I did [the folk standard] ‘Goodnight, Irene’ in the Underground Piano Bar at two in the morning. So, I do get involved. I’m on my feet the whole weekend doing stuff.

I also spoke to the Beanfield people, because it was the 30th anniversary of ‘the Battle of the Beanfield’.6See ind.pn/1UhPuiW. [In 1985] they were turned away from Stonehenge because Michael Heseltine [then Secretary of State for Defence] thought that they were a threat to the nation, so they came to my place. I thought originally that they were going to be nasty, because of all the media stuff, d’you know what I mean? With machetes and stuff. But they were not like that at all. I actually got on with them really well. Extraordinary!

The Glastonbury Festival is now seen to epitomise the best of British culture –

I hope so.

– but it started off as a very alternative…

Well, it is [that], too. We’ve managed to create [a festival where almost] 200,000 people all get on with each other – you know, all mixed races, all mixed-sex. There is no nastiness anywhere. None. Isn’t that extraordinary?

This is a British culture that brings people together, you know. I mean, it’s not about fox hunting and the Changing of the Guard – there are other things going on that people can identify with: getting on together, sharing their experiences, sharing their food, sharing their music and sharing their art and everything. That is my greatest achievement, I think, really.

Is that what you would like to be remembered for?

I suppose so… I just want to try to hold this society and hold it together, so that they’re enjoying themselves together and appreciating the same things. I mean, we’re all part of the creation of God or whatever. We’ve got different creeds and different beliefs and stuff but there is a common thread there and it all comes together at Glastonbury. That’s why it works. That’s why it works. Oh, it’s a massive success.

Do you see it as a model for what society could be?

I’m not showing off, am I? I don’t want to show off or anything…

Go on!

No, but I was so thrilled that this year particularly, with all this stuff going on about Muslims, we had thousands and thousands of Asians. People were coming up to me and [telling me,] ‘Oh, Michael! We haven’t been to this before. We’ve just discovered it.’ That’s so good, isn’t it? It’s so satisfying!

No, but I was so thrilled that this year particularly, with all this stuff going on about Muslims, we had thousands and thousands of Asians. People were coming up to me and [telling me,] ‘Oh, Michael! We haven’t been to this before. We’ve just discovered it.’ That’s so good, isn’t it? It’s so satisfying!

How much of these values are a legacy of the chapel?

It’s probably inherited from my family’s Methodism – being friendly, being sociable, being jolly and not too much drinking, d’you know what I mean? I mean, you can do all that without being drunk. My father used to run tennis parties in the village, and people always gathered at the farm – though not on the same scale! It was always a friendly place.

You take a minimal salary, is that correct?

Actually, I didn’t take it last year. Nor the year before, funnily enough. Officially, I get £60,000 a year salary. But I’m not pretending I’m poor or anything. I have an income from the farm and I am well off.

John Wesley said: ‘Earn all you can, save all you can, give all you can.’

Yeah, that’s great. I love that! It’s a classic statement.

And you do give a lot of money away.

From the festival, we donate £2 million a year to all the good causes we support. We’re divvying it out, basically, so that people get the benefit of all that money that is created at Worthy Farm. I get an incredible amount of pleasure from dishing stuff out. I’m doing it every day. It sounds a little bit benefactorish, I know, but we have the money and I decide where it goes. People write to me every day and I give out £25 here, £500 there. I just read the letters and make my mind up about how much we’re going to give.

So, it’s not just the big charities such as Greenpeace, Oxfam and WaterAid that you support?

We do little ones as well. And stuff goes to the chapel – and even the Church of England, even though we are supposed to be rivals! We were always rivals, years ago, because they were establishment and [the Methodists] were sort of working-class or yeoman types.

This is a very strong Nonconformist area. There are the Quakers in Street, the Methodists in Pilton… I did a talk at Lyme Regis the other day for the University of the Third Age and there was a woman there from this area and she said that the festival wouldn’t have survived anywhere else in the country. Just here it works, because there’s a strong nonconformist and anti-establishment tradition. She made that observation and she was, like, a professor of something, looking into fossils on the Dorset coast. And I think it was really astute.

The worrying thing is whether the new generation of kids have got the grounding that I had. I’m very chuffed with my life, but what about everybody else out there?

I understand that you don’t like taking foreign holidays. Have you been abroad?

Oh, just occasionally, yeah. But sitting on the beach in the south of Spain drinking gin and tonic just doesn’t appeal to me at all. We’d rather pop down to Cornwall for a long weekend or something every now and again.

Do you buy yourself luxuries of any kind?

Oh yeah. I mean, we have a good life, really. We eat out quite a bit. I bought a little Mini 14 years ago as a wedding present for my wife. She didn’t drive it for a year – she was embarrassed. She does now, though. I ask her, ‘Should we change it for something slightly more comfy?’ and she says: ‘No, no, I want to keep it!’

I have got Land Rovers, and two or three bikes. You know what I mean? I’m not suffering.

Your style of beard is quite religious, isn’t it, like those worn by the Amish and the Mennonites. They renounced moustaches originally because they saw them as a mark of pride. Was that your thinking?

It’s not that. It’s for kissing! That’s the secret.

Did you ever have a full beard?

Yeah, I did try it once. I didn’t like it.

You didn’t like it or she didn’t like it?

The girl didn’t like it, either!

Do you have any hobbies – other than kissing?

No, I’m afraid not. We walk for miles along the coast in Cornwall, but that’s not a hobby, is it, really?

Do you ever feel as though you’re leading three different lives? You’re down with the cows, you’re in chapel and then you’re on stage with the Rolling Stones.

Yeah, but it’s all good – it all works together. Oh, it’s a hell of a good life, isn’t it? It’s a hell of a good mix. But I do run for cover to the chapel on Sunday mornings.

You run for cover? Why?

I don’t know. I get some sense of security.

We go to chapel every Sunday morning without fail for an hour and do the whole thing with the children and Sunday school and all that stuff, d’you know what I mean? And it’s really important to me. The worrying thing is whether the new generation of kids have got the grounding that I had. I’m very chuffed with my life, but what about everybody else out there?

Do your grandchildren go to chapel?

The birds sing their heads off first thing in the morning and last thing at night but they don’t understand what God is, do they?

Yeah.

How can the church today compete against the best that entertainment can offer?

I don’t know what the church can do. It’s really worrying, isn’t it? I mean, at our little chapel we’re about 35 people, which is not bad in a village of 900, is it? But I can get 200,000 people together on the farm – and we sell all the tickets within 30 minutes. There is huge demand and it’s increasing all the time. It’s unbelievable, really, isn’t it? And yet the chapel – young people are not interested in that. They get put off, don’t they, by all sorts of things.

You wouldn’t want your chapel to be more entertaining, though, would you? You wouldn’t want flashing lights.

No, I wouldn’t want to change it. I quite like the old-fashioned style of it. The old preachers that do really well are fundamental believers in the word of the Bible and stuff and it’s good listening to them.

I really don’t know how to get that across to young people, or whether they need it or not. I’m not absolutely sure that they need it – but I think they do, actually.

Do you think that rock music in a way addresses that part of people that preachers used to address?

I don’t know. I think that the whole social thing – as I said, living together and getting on together and enjoying themselves – that’s similar, really, to a religious experience, isn’t it? It’s not quite the same, though, is it?

If you didn’t have chapel, do you think you’d be more egotistical or…?

I do hope it’s made a difference, to my social attitudes and things. I’m sure it has – all that preaching and E P Thompson and stuff.

I can’t understand why you’re not convinced about God.

I don’t like to [claim] there’s something out there that I can’t really prove, d’you know what I mean?

But isn’t it fundamental? You’re worshipping God…

But it’s not abundantly clear what God is, that’s the problem.

Yet you still sing praises to him?

Yeah, I do. I love singing. Praise to the Creator, yeah – oh my God, yeah! There’s nothing like it. The birds sing their heads off first thing in the morning and last thing at night but they don’t understand what God is, do they?

You identify with the birds?

Yeah!

And they don’t read the Bible, either.

No, they don’t! No, they don’t!

Are you a fan of William Blake?

Yeah, I do love William Blake. I don’t really understand him, though. Nobody does.

I had colon cancer about 20 years ago and I was off work for about three months, so I read the whole of that biography of Blake by Peter Ackroyd.7Blake (Sinclair-Stevenson, 1995) And another one.

Was that a worrying time for you, when you had cancer?

Well, I thought I might die, obviously. My father died of colon cancer. I might have prayed, actually. I said I didn’t pray but I might have prayed on that occasion.

But then you stopped?

Yeah.

‘I haven’t heard from that Michael Eavis for ages!’

I know, it’s not fair, is it? It’s really, really mean.

This edit was originally published in the September/October 2015 issue of Third Way.

To make sure you hear of future interviews in this series, follow High Profiles on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

| ⇑1 | Most notably, Fleetwood Mac, John Mayall, Ten Years After, Led Zeppelin, The Nice and Chicken Shack |

|---|---|

| ⇑2 | See bit.ly/1IzSvCP. |

| ⇑3 | ind.pn/1MRvMIH |

| ⇑4 | Ballantine Books, 1969 |

| ⇑5 | See bit.ly/1SVoW4m. |

| ⇑6 | See ind.pn/1UhPuiW. |

| ⇑7 | Blake (Sinclair-Stevenson, 1995) |

To find out more about the agenda behind our interviews, read our manifesto. To access our archive of more than 260 interviews, see the full list.

Biography

Michael Eavis was born in 1935 and grew up on Worthy Farm in Pilton, Somerset. He attended Wells Cathedral School and then went to HMS Worcester (now the Thames Nautical Training College). At the age of 17, he joined the Union-Castle Line as a trainee midshipman. He returned to Pilton in 1954 after his father died.

He inherited the 150-acre farm and 60 cows in 1958. He then worked at Mendip Colliery for two years.

In 1970, he organised and hosted the Pilton Pop, Folk and Blues Festival, which was headlined by Tyrannosaurus (later T) Rex after both the Kinks and Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders dropped out. Admission cost £1 and included free milk.

After two further festivals at Worthy Farm in 1971 and ‘79 (instigated by Arabella Churchill and others and billed as ‘the Glastonbury Fair’ or ‘Fayre’), he organised the first Glastonbury Festival proper in 1981 as a benefit for CND. New Order, Hawkwind, Taj Mahal, Aswad and Gordon Giltrap performed and 18,000 people paid £8 to hear them.

The festival (renamed ‘the Glastonbury Festival for Contemporary Performing Arts’ in 1990) has since been an annual fixture, save for the ‘fallow years’ of 1988, 1991, 1996, 2001, 2006 and 2012.

By 1985, ticket sales had risen to 40,000 and extra land was bought to accommodate the festival. The following year, attendance reached 60,000. The festival was first televised, by Channel 4, in 1994, with the BBC taking over in ’97. Attendance topped 100,000 in 1998 and hit 140,000 in 2002.

In 1997, Eavis stood for Parliament as the Labour candidate for Wells, gaining 10,204 votes.

He was made a CBE in 2007 ‘for services to music’.

He has an honorary doctorate from Bath and an honorary master’s degree from Bristol University.

In 2009, nominated by Chris Martin of Coldplay, he was named by the magazine Time as one of the 100 most influential people in the world.

He has three daughters from his first marriage, which ended in 1964, and two children from his second. He married for the third time in 2001. He has, besides, five stepchildren and 17 grandchildren.

Up-to-date as at 1 August 2015