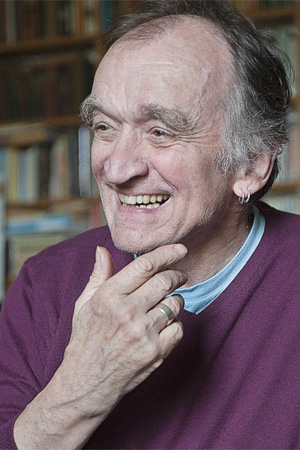

Martin Carthy

has progressed over more than half a century from being the ‘crown prince’ of British traditional music to its ‘godfather’. Simon Joseph Jones played it by ear at his home in Robin Hood Bay on 28 May 2013.

Photography: Andrew Firth

Am I right in thinking that your first musical experience was in a church choir?

Yeah, I suppose it was. Even before that, my sister and I would go to church and we always sang very loudly.

My first professional experience was when I was a chorister at the Queen’s Chapel of the Savoy. The school I went to, down by Tower Bridge, supplied the choristers for Southwark Cathedral and the Savoy Chapel, and I was rejected for Southwark Cathedral. The music was beautiful – Orlando Gibbons, Thomas Tallis, with a bit of Vaughan Williams thrown in. For a long time, that was my take on what English music was, so when I came across folk music, oh boy, was that a wake-up call!

How did you discover that?

One of the kids in class said, ‘Have you heard this song “The Rock Island Line” by this bloke Lonnie Donegan?’ I had a listen and thought it was absolutely wonderful.

Lonnie Donegan triggered this massive regeneration, if you like, of popular music – people’s music – and the folk revival was definitely a part of that. He had not the faintest idea of the effect he had. I mean, I can’t imagine how many hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of guitars were sold on the strength of ‘The Rock Island Line’. And there were no teachers, there was no tablature; all you had was the records, so you’d slow them down and just try to work the thing out. It meant that my generation developed really good ears.

Was there much music in your family?

There was music appreciation, but there was a lot of snobbery. My mum had been present on the fringes of the earlier folk revival in the Twenties and Thirties, but she was there because of politics. There was a clergyman called Conrad Noel, in Thaxted, about 40 miles outside London, who was known as ‘the Red Vicar’. He put up in his church the red flag, the flag of St George and the flag of Sinn Féin – in 1919! And in 1911 he infuriated people because he started the first revival Morris team and had them dance in the church. It was unheard of!

What was your father like?

He was an East End boy. He was the first one in his family who wasn’t a Thames lighterman since they first came over from County Kerry and Ulster – because he won a scholarship to [the grammar school I went to].

It’s far too easy to become exclusive, it’s far too easy to start excluding people who don’t agree [with us]; and that’s not the idea. One has to get used to the idea that Tories like folk music, too, you know?

He worked for the TUC and was involved in Labour Party politics – he would go out canvassing two or three nights a week in Hampstead and get abused a lot, because at that time it was a Tory stronghold. There was a lot of snoot around, but lots of working-class Tories, too.

Was the politics important to you at all back then?

I was very much an innocent.

How did you find your way into the folk scene?

I explored a bit of Woody Guthrie but not so much. The repertoire was hard to come by – you grabbed what you could. There was a small circuit. I used to go down to the Troubadour in Earls Court – I got to see all sorts of people there.

It was in the Sixties that people first started to become aware of you and your playing. Did it feel at that time as if something momentous was happening?

Oh, yeah. Starting with skiffle, we – and there were a lot of us – we thought that we were really onto something. When people said we were rubbish, we used to get really superior. You’re very arrogant at that age.

Was that tied in with the spirit of the Sixties – ‘The Times They Are a-Changin’’ and all that sort of thing?

God, yeah. The British Isles folk revival was very much modelled on the American folk revival. Pete Seeger was hugely admired – hero-worshipped. I remember when he came over in the early Sixties – he had been found guilty of ‘un-American activities’, but the appeals system had [overturned] it – it was a celebration, almost, of his right to travel. He played at the Albert Hall and the place was absolutely heaving. We definitely modelled ourselves on people like him, and on groups – they didn’t call them ‘bands’ in those days – like the Weavers.

Is it true that it was a Bob Dylan lyric that convinced you personally of the power of narrative song, rather than anything more traditional?

Yeah. It was ‘The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll’. He sang it at the Festival Hall in ’64. It was astonishing. The place exploded when he finished!

The thing about Bob Dylan is that he is one of the few – the only – rock’n’rollers who actually understand folk music, understand tradition, understand the nature of it. He gets it. Others pay lip service.

One criticism made of folk music is that because it has a political agenda – flowing from the belief that the music of the people is important – it’s dogmatic or didactic.

Well, there was a lot of that, and there probably still is, though I think it’s loosened up a lot. I remember seeing myself on television being interviewed by John Craven and talking a lot of claptrap and I thought: ‘What are you saying? You don’t believe that. Stop it!’

It’s far too easy to become exclusive, it’s far too easy to start excluding people; and that’s not the idea.

Excluding what kind of people?

People who don’t agree [with us]. One has to get used to the idea that Tories like folk music, too. You know?

And not just Tories. I read that Nick Griffin1Interviewed for High Profiles in May 2004 is a big fan of Kate Rusby and [Eliza Carthy,] your daughter.

I’m afraid so. Some guy wrote an article which said: ‘No prizes for guessing the BNP chieftain’s favourite type of music. Yes, it’s that most arthritically white of genres: English folk.’ Eliza wrote a great piece for the Guardian and went straight for the throat.2bit.ly/alt2a2

The audience is an equal partner in a live performance – they do as much as you do. There’s an interchange going on, a thing that arises between you – it’s like a ghost you have created between you

You can see why some people see it that way, though. The idea of folk may be that it’s the music of the people, whoever they are and wherever they’re from, but in practice the genre is generally very white.

Well, it has been in the past, but that’s not the fault of the music. That’s just the way it was.

But one has to get used to the idea that all notions are covered in folk music, including some you don’t particularly like and some you’re absolutely opposed to but that’s what some people think, or thought in the past. I remember a musician friend who said: ‘I think we’re librarians, so therefore we should sing everything.’ And I said: ‘I couldn’t agree less.’

So, how do you go about choosing a repertoire, when so many old songs have sexist or racist lyrics?

Well, I’ll give you an example of one that was a turning point for me. I always look for a nice tune, and there’s one particular song called ‘The Man of Birmingham Town’ – ‘The Man of Burnham Town’ was the way I did it. It’s 18th- or 19th-century. And the story is that a man goes off to sea and when he comes home he hears that his wife is down the pub, carousing and having a wonderful time – and he is outraged. And the song tells you that he beats the shit out of her and she deserves it.

Now, I recorded that with Dave Swarbrick [on] an album called Byker Hill [1967]. And then we sang it in a club – because it’s a great tune – and when I got to the lines ‘He took a stick and he beat her/Till she was wonderful sore’ and then ‘Oh husband dear, I’ll never do that no more,’ I swear to God I felt the audience freeze. It was so unexpected from us, because we sang a lot of songs about sexual politics. We never sang it again.

So, you were guided by the audience reaction?

It’s not a question of doing what the audience wants, it’s a question of understanding that the audience is an equal partner in a live performance – they do as much as you do. That’s what’s great about doing it in a small room: there’s an interchange going on, there’s a thing that arises between you and the audience – I can only describe it as like a ghost you have created between you.

I’m still not sure how you decide what is proper to sing and what is not.

Well, I think I trust myself, and I trust…

Let me go back. When I sang that particular song, it was in the Sixties and wife-beating was becoming more and more [unacceptable]. It took the law quite a time to catch up – at that time the police would say, ‘Oh, it’s a domestic. It’s nothing to do with us’ – but among ordinary people it mattered. The fact that it was happening in this song and I was presenting it as something that was OK – ‘No, no, that won’t do.’

The older songs are much, much subtler. They very rarely tell you what to [think] but they make it very clear whether what is happening is acceptable or not. A lot of the songs are about lords and ladies: ‘That’s how they behave. Do we like that? No, we don’t.’

My very favourite song, ‘Prince Heathen’, tells you very clearly that in a domestic-violence situation it’s not OK for the husband to say, ‘Oh, but I love you’ and the wife to say, ‘Oh well, that’s all right! Never mind the bruises and the broken ribs.’

Still thinking about Nick Griffin, there are folk songs that are resistant to the idea of immigrant labour, let’s say.

The Labour Party and the unions used to be against it, didn’t they? Cheap labour and all that. But now things have turned over, and that’s as it should be.

If folk music presents us with a vision, a history and a tradition of what human beings believe and feel and how they behave, does that leave you feeling hopeful or fearful for humankind?

Well, I’m amazed and thrilled by the conclusions my ancestors reached on the subject of domestic violence. Is that too pompous? They said: This is not all right. It’s a very old notion, and it’s the same notion that Gandhi preached, which was firmness in the truth. You tell the truth all the time, and sometimes it’s extraordinarily uncomfortable, but it’s clear where you stand.

Well, I’m amazed and thrilled by the conclusions my ancestors reached on the subject of domestic violence. Is that too pompous? They said: This is not all right. It’s a very old notion, and it’s the same notion that Gandhi preached, which was firmness in the truth. You tell the truth all the time, and sometimes it’s extraordinarily uncomfortable, but it’s clear where you stand.

There are songs about incest, whether it be brutalising incest or two people who fall in love and they happen to be brother and sister, only the sister wasn’t born when the brother went away. A song is capable of presenting you with the horror of the thing. There’s always a casualty, and it’s usually the woman.

There are songs about racism, like ‘Lord Thomas and Fair Eleanor’, where Thomas has got no money, his one true love, the Lady Eleanor, has got no money, but the Brown Girl has; so Thomas leaves his true love and marries the Brown Girl and then proceeds to invite his true love to the wedding and insult the Brown Girl. So, the Brown Girl kills Eleanor. And then he chops the Brown Girl to pieces in front of everybody, and falls on his sword. To me, it’s absolutely clear who the baddie is and it’s not the Brown Girl. She’s driven to it by these dreadful people!

You’ve said that folk music is by definition subversive…

Yeah. It insists that you think.

‘Subversive’ implies that it insists you think a certain way.

Well, anti-establishment, I would think.

Is it by definition anti-establishment because it’s done by people who aren’t part of the establishment?

It’s made by people who think for themselves. Most of it – I mean, we can all think of songs that go against that.

But if we say that folk is music that is made by ‘ordinary people’, you could argue that an ordinary person, now and through history, might as soon be a conservative as a progressive. Ordinary people may not create music –

That you like, or you approve of? Yes. I can’t but agree with that – but that’s why I make choices.

Also, there’s a whole part of folk music that is dealing with a situation [of its day] – it’s saying, ‘No wonder your butter’s now tuppence a pound!’ – but it has at its root a notion that can be used again and again and again: ‘Honesty’s all out of fashion./These are the rigs of the time.’ And then you make your extra verses.

‘Working Life Out to Keep Life In’ is another song like that:

No matter, friends, whate’er befall,

The poor folk they must work or fall.

Through frost and snow, through sleet and wind,

They work life out just to keep life in.

I wrote some extra verses for that that were appropriate for nowadays but included that old notion.

A lot of songs about the Peninsular War you find turning up again in the Crimean War, you know? So, now you put them in Afghanistan or whatever.

Like ‘The Dominion of the Sword’, with its references to South Africa and the Rainbow Warrior?

Yeah. My mum gave me a Penguin anthology of war poetry when I was 18 or a bit older and I found ‘The Dominion of the Sword’ in there. I was blown away by it – I used to read it again and again and again. I didn’t understand all the references – my history is not that good, and a lot of it is very particular – but some of it applies absolutely right now.

The first thing I added was:

My feeling is that tradition is a progressive force. (I like the idea of it being progressive with a capital P as well, and it sometimes is – but not always.) It always moves. It changes, willy-nilly. You change

Kruger, Krugerrand-a, whither do you wander?

Gone to the suborning of Hastings Banda.

There’s a real rage in that song –

Oh God, yeah.

There is a passion in a lot of the music you do. Is that what dictates where you put more of your own words into a song?

Well, at that time I’d written a couple of songs, having never written a song from scratch in my life. I wrote them as a direct result of the awful Margaret Thatcher.

I was with the Watersons at this festival down in Telford at the time of the Falklands war. All the people there were real radicals and there was a lot of comedy there, and street theatre, and lots and lots of politics. And this guy stood up and sang a song called ‘Ghost Story’ about the Falklands war – the first song I’d heard about it – and a lot of the audience booed him. I can’t tell you what a wake-up call that was. The Watersons and I just stood and gaped. We were horrified.

I realised that if the war had happened 20 years earlier, there would have been 20 or 30 songs written about it, because it was that political then, and I would have been a part of that. So, I wrote ‘Company Policy’.

Another criticism of folk is that it is fearful of the future, or even the present.

Well, there is a lot of that about; but my particular feeling is that tradition is a progressive force. (I like the idea of it being progressive with a capital P as well, and it sometimes is – but not always.)

Progressive in what way, then?

It always moves. I know that the way I sing ‘Prince Heathen’, for instance, is nothing like the way I sang it when I learnt it, in 1969. It changes, willy-nilly. (I happen to think it’s a fabulously progressive-with-a-capital-P song as well.) You change. You will be different in 10 years’ time.

But you could be better or worse.

You hope you’re better. You know, my one ambition is to get better at my job.

I didn’t mean better in terms of your craft. I meant that the human race can progress or it can regress.

Yeah. In the late Seventies, early Eighties, I realised that we’d just got lazy and gone backwards. What do you do? You do something about it.

When the punks hit with the [Sex] Pistols, that was another wake-up call. It had a galvanising effect.

I’ve heard you’re a fan of punk rock.

Oh, yeah. Oh, the Pistols were fabulous! I thought I recognised exactly the same spirit there as was released by skiffle. You know: ‘Screw you! What do you know? You don’t know anything.’ Oh, it was just wonderful, a wonderful release. I started examining my repertoire and I began ditching a few things that had nice tunes and I could play them and I really enjoyed playing ’em but they didn’t really say anything.

You turned 70 a couple of years ago and you’re always referred to now as a legend –

I’m not a legend, I’m a working musician. I regard myself as being like anybody else, whether they’re 20, 30, 40, 60, whatever. We’re all in this together. You know, we are colleagues.

There is no age limit for a folk musician, is there? No one ever expects you to stop.

There is no age limit for a folk musician, is there? No one ever expects you to stop.

Well, what is a retired musician? Tell me, and I’ll think about retiring. No, I won’t – fuck it, there’s too much to learn. There’s too much to find out!

BBC4 did a documentary on you3Martin Carthy: English Roots (2004) and I remember you watching yourself as a young man on TV and rather lamenting your playing style…

I remember that moment and what I actually said was, I looked at [the clip] and I said: ‘It’s well played and it’s well sung, but it’s done.’ I’d never done that song before and I decided to do it on television and I did it and I got it absolutely right. What I wanted to do, I got exactly. And I never sang it again. I’m really proud of having got it absolutely right, make no mistake; but [to have sung it again would have] required a piece of timing to be exactly the same every time, and you can’t do that to folk music. It has to be free.

I was interested in the idea of you looking back on yourself as a young man. You must see songs differently as you age. Is that so?

Absolutely, yeah. Well, I’m sure it’s true, but I felt it for the first time the other day. It’s 50 years since The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan [came out] and so [BBC Radio 2] got a whole lot of folkies and near-folkies, including me, to do the songs and they asked me to do ‘Bob Dylan’s Dream’. I sang it and it was quite wistful, and I remember thinking: ‘You’re singing it just like an old man. You wouldn’t have sung it like that back then, if you’d ever sung it.’

Has age made you more wistful?

With some songs, yes, certainly. Certainly with a song like that, when it’s looking back. I mean, it’s extraordinary that Dylan was able to write a song like that when he was 22, 23 years old.

There’s a perception of you as a family man, I think, partly because of the Watersons, partly because you sing with your daughter and your wife. On Desert Island Discs, you picked a song by your daughter. Is the idea of being a family man something that is important to you?

Well, when I married [Norma Waterson] I was welcomed into this huge family, and I began to understand what it means. The Carthys in the East End were a big family, but they were broken up by the Blitz and where they are now I really don’t know.

So, were you discovering something you felt you hadn’t had before?

Yeah. Yeah. It was not a lack of love but just that my dad was not settled in what he was. Part of me understands it – that he was a man of his time and that when you bettered yourself you left your old life behind – and part of me finds it inexplicable. I can think of maybe five or six things that he told me about his life as a kid and that’s it. He had loved to play the fiddle when he was a young man, and he never, ever told me. I knew he had a fiddle in the back room, which he never played because my mum didn’t like it. He didn’t approve of what I was doing. He thought I should be going to university and doing classics – that was his dream.

Do folk music and family fit together for you in a way that is not just circumstantial?

Yes. Especially since becoming a grandfather. I’ve often talked about being links in a chain musically, and that’s the way I understood it. You find yourself talking in clichés, like ‘I’m standing on the shoulders of giants,’ and it’s all true – but when it really comes home to you, that really and truly that is what it’s about, [is when] you’ve got a grandchild. This is the child of your child. It’s a quite extraordinary feeling, and so different from being a parent. A door opens, you know, and that’s the future: ‘Oh yeah, that’s right, it’s a chain.’

The church is not a part of your life any more, is it?

No. But I recognise it as being important. There’s bits of it I really don’t like at all, but…

Which bits in particular don’t you like?

I don’t like ‘The rich man in his castle,/The poor man at his gate’. I’m not crazy about ‘Onward, Christian Soldiers’. I do not like the Church Militant one tiny bit.

If you present people with something that really rocks them back on their heels, they will embrace it. I think. I hope. No, I believe it. I have faith in people. I do. I am optimistic

There are people in the church who would see hymnody or folkish choruses as part of their folk music. Would you accept that?

In its way, yeah. Especially the stuff that comes before The English Hymnal and Hymns Ancient and Modern – stuff like Moody and Sankey, which is far more rough- and-ready and hairier. I have a huge soft spot for ‘For those in peril on the sea’. Some of those hymns are just so straightforward and honest, and they really do express people’s feelings. I can’t dismiss them out of hand.

You’ve recorded ‘Christ Made a Trance’…

I love that song – it’s very mysterious. There’s something about Gypsy carols and hymns that always really bites deep. I think it’s the passion of those hymns that attracts me. Genuine, heartfelt passion – how can you possibly resist it?

Gypsy is not part of your heritage, is it?

It’s part of Norma’s – but I would sing them anyway.

Is that not appropriating somebody else’s tradition?

Of course it is. I’m a Johnny-come-lately, so the whole thing is an appropriation and I think it’s my job to maul it about.

Your job because you’re a Johnny-come-lately?

No, no, because I’m who I am. Because of what I do. I want to sing these songs, and I want them to be… I don’t believe in the idea of bringing them up to date, but I do think sometimes that the language has to be blunter. It means I lose some poetry, but I also gain some, because inevitably you’re going to find something that’s good.

Generally in the music business everyone tries to claim ownership of a song, to get the copyright and so on. Does the total commercialisation of music endanger folk?

I’ve done all sorts of rewriting with some of the big ballads, and I insist that it has to be ‘trad. arranged’. I think that we’re duty bound to say that.

It flies in the face of the whole idea that you can’t have art by committee. It is a committee – it just happens to go back a few hundred years and you’ve never met any of them. And there’s going to be more people in the future, touch wood, provided nobody copyrights it.

Many people who are not fans of folk music think of it as all beards and real ale. Do you have any sympathy with that view of it?

I think if you put them up in front of somebody who’s really passionate about it and really digs in when they perform, they will respond. If you present people with something that really rocks them back on their heels, they will embrace it. I think. I hope. No, I believe it. I have faith in people. I do. I am optimistic.

Are you optimistic about the future of traditional music?

I don’t see why not. I mean, there’s in-fighting all the time – you know what the left is like. But there’s a lot of people who genuinely, genuinely get it, and they’re passing the idea on. And as long as that happens…

This edit was originally published in the September 2013 issue of Third Way.

To make sure you hear of future interviews in this series, follow High Profiles on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

| ⇑1 | Interviewed for High Profiles in May 2004 |

|---|---|

| ⇑2 | bit.ly/alt2a2 |

| ⇑3 | Martin Carthy: English Roots (2004) |

To find out more about the agenda behind our interviews, read our manifesto. To access our archive of more than 260 interviews, see the full list.

Biography

Martin Carthy was born in 1941 and grew up in Hampstead, in north London. He was educated at St Olave’s and St Saviour’s Grammar School for Boys.

He left school at 17 and worked for 18 months in the theatre as an assistant stage manager. In the early Sixties, he became a resident guitarist at London’s top folk club, the Troubadour (where he taught songs to Bob Dylan and Paul Simon among others).

He joined the Thameside Four in 1961 and recorded with the Three City Four in 1965, before teaming up with the fiddle player Dave Swarbrick to record his first album, Martin Carthy (1965). He has since made six further studio albums with Swarbrick – Martin Carthy’s Second Album (1966), Byker Hill (1967), But Two Came By (1968), Prince Heathen (1969), Skin and Bone (1992) and Straws in the Wind (2006) – and nine without him: Landfall (1971), Shearwater (1972), Sweet Wivelsfield (1974), Crown of Horn (1976), Because It’s There (1979), Out of the Cut (1982), Right of Passage (1988), Signs of Life (1998) and Waiting for Angels (2004).

In 1972, when he married Norma Waterson, he also joined her vocal group, The Watersons. With them he has recorded For Pence and Spicy Ale (1975), Sound, Sound Your Instruments of Joy (1977), Green Fields (1981) and A Yorkshire Christmas (2005). With his wife and their daughter, the virtuoso fiddle-player Eliza Carthy, he has recorded Waterson:Carthy (1994), Common Tongue (1996), Broken Ground (1999), A Dark Light (2002), Fishes and Fine Yellow Sand (2004) and Holy Heathens and the Old Green Man (2006).

He has done two stints in Steeleye Span, with whom he recorded Please to See the King and Ten Man Mop (both 1971), Storm Force Ten (1977), Live at Last! (1978) and The Journey (1999); and was a member of the Albion Country Band in 1973, recording Battle of the Field (released in 1976). He has also been a member of the ensemble Brass Monkey, recording Brass Monkey (1984), See How It Runs (1986), Sound and Rumour (1999), Going and Staying (2001) and Flame of Fire (2004), as well as the folk supergroup Blue Murder, recording No One Stands Alone in 2002.

In 1998, he was made an MBE for services to English folk music. He was named folk singer of the year at the BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards in 2002 and ’05, and in 2007 he and Swarbrick were named best duo. He has an honorary doctorate from Sheffield University.

Up-to-date as at 1 June 2013