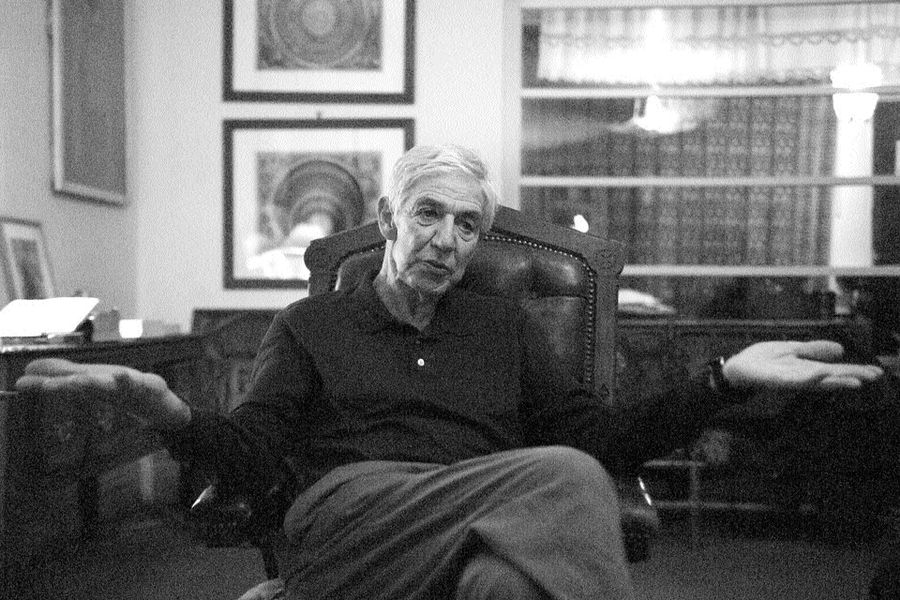

Lewis Wolpert

was a prominent developmental biologist, author and broadcaster who firmly believed that ‘science is the best way to understand the world’.

Keith Ward called on him at his flat in London on 17 January 2007.

Photography: Andrew Firth

First of all, can you tell me a little bit about your background and about how it shaped you? You grew up in South Africa, I believe.

Yes, in a moderately conservative Jewish family, religious but not Orthodox. I did civil engineering at university – I was quite keen on being a mathematician, but I wasn’t good enough. I was quite involved in politics – the Communists and the African National Congress. I wasn’t a member of the Party, but my friends were, and every Sunday morning we went to the townships to sell the Communist newspaper. I knew [Nelson] Mandela – not well, but when I left South Africa (in part, because I wanted to get away from my parents), I carried a letter of introduction from him to other African groups.

I went to Israel for a year, where I worked on a dam north of Haifa; and then I came to London and that was magic. I can only say that everyone in my academic life here has been lovely. (My joke is that being not English in London is an enormous advantage, because you can behave badly and people forgive you because you’re not part of the class system.)

Were you religious when you were young?

Oh yes! Oh yes! My mother made me go to synagogue every Saturday morning when I was young, and I had a bar mitzvah. I learnt Hebrew privately, though I didn’t do well at it. I said my prayers every night. And then I stopped believing in God when I was about 15 or 16 because he didn’t give me what I asked for. So, I gave it up.

And it’s never attracted you since?

Never, no. Oh, I can see the attractions. As I grow old now and death is around the corner, I can see the attractions of believing in heaven.

I don’t try to persuade people not to be religious. I wouldn’t do that. I attack religion only when it interferes

Well, maybe it’s not too late.

I think the evidence for God is not very good from my point of view.

Ah, now that’s a different issue.

It is – and it’s not the way I thought then. It was a practical issue for me then.

You felt then – to put it crudely – that religion didn’t do anything for you. Did it do anything for anybody else? Do you have any sense now that Judaism has done something for the world?

Certainly, I think religion can hold people together – there are books that argue that one of its functions is to create a community with shared ends, in which people help each other. Take the Jewish community in London (which I am not involved in): I think they have found it very supportive. They certainly did in South Africa. I think my parents were helped by religion. I even had my two sons circumcised – I’m a bit shocked by that now.

No, I think that for many people religion is very helpful. It was for my son. He was going through a critical period and he was evangelised by the London Church of Christ and became deeply religious. People kept saying to me, ‘Aren’t you terribly upset he’s become a Christian?’ And I said, ‘Absolutely not! It’s helped him.’ I said to him, ‘Did I ever try to persuade you not to be religious?’ and he said, ‘You never did.’ I don’t try to persuade people not to be religious. I wouldn’t do that.

You quite often talk about it.

I attack religion only when it interferes. I attack the church if they say a fertilised egg is a human being. I attack [George W] Bush and that rubbish about stem cells.1See researchamerica.org/advocacy-action. I’m against the Catholic Church because they ban contraception. You know, those sort of things.

But, you know, as long as you don’t try to affect other people’s lives, I have no objection to religion whatsoever.

Right. So, you don’t feel that religion is an evil –

I think it can be evil. But then, listen, so can communism, so can all sorts of things – and you can be evil without any of these things.

So, you wouldn’t agree with Richard Dawkins –2Interviewed for High Profile in February 1995

No.

– that the human race would be better off without it.

No, I think we’d probably be worse off without it. I think people need it.

Right. You’re a vice-president of the British Humanist Association –

I think there are lots of vice-presidents, and I’m one of them. I’m not really involved with them in any way.

I proclaim myself as an atheist. There is absolutely no evidence for the existence of God, just as there’s no evidence for fairies at the bottom of the garden

How did you become a vice-president, then?

I haven’t the foggiest notion.

You don’t proclaim yourself as a humanist?

I proclaim myself as an atheist. And as a reductionist and a materialist.

Being an atheist is a very strong position. It’s always harder to deny that something exists anywhere.

I just say I don’t believe in God. There is absolutely no evidence for the existence of God, just as there’s no evidence for fairies at the bottom of the garden.

What sort of evidence would count for you? Would it have to be scientific evidence of some sort?

Well, no… I think I read somewhere: If he turned the pond on Hampstead Heath into good champagne, it would be quite impressive…

A miracle would be sufficient?

But then you have to remember what David Hume said, that you wouldn’t believe in a reported miracle unless ‘the falsehood of [the] testimony would be more miraculous than the event which [it] relates.’3‘When anyone tells me, that he saw a dead man restored to life, I immediately consider with myself, whether it be more probable, that this person should either deceive or be deceived, or that the fact, which he relates, should really have happened. I weigh the one miracle against the other; and according to the superiority, which I discover, I pronounce my decision, and always reject the greater miracle’ (An Enquiry concerning Human Understanding, 1748).

It’s one of his worst arguments, in my view.

Hume is the only philosopher I take seriously. I’m big against philosophy. I’m sorry – I know you’re a philosopher! I have lots of friends who are philosophers and I know they’re terribly clever.

Do you think that in science as you practise it there is room not just for strongly evidenced theories but also for hypotheses that are elegant or satisfying in a general sense?

Only if they explain things you haven’t been able to explain and there’s a bit of evidence for them.

There isn’t any evidence for superstrings, is there?4String theories propose that ultimately matter is composed not of particles but of strings, whose vibrations give them the appearance of the different kinds of particles physicists have observed. These theories seem to go some way towards explaining and reconciling the four fundamental forces in nature – electromagnetism, the strong and the weak nuclear force and gravity – but they also seem to require the existence of (maybe many) more dimensions than we experience.

I’m out of my depth here, but apparently the whole theory has collapsed – did you know that? Because there’s absolutely no evidence for it.

But aren’t there things in science that people take seriously –

And can investigate, yes. In the long run, you’ve got to have evidence.

In the long run, of course, we’re dead. Might there be evidence for God after we’re dead?

Well, I have thought: Won’t it be funny if it turns out that I’m wrong? But God is not a theory like superstrings, no. I don’t think there is anything that usefully God explains. Because you’d have to explain where God came from and what the nature of God is, and no one ever gives that explanation.

I think there is evidence that religious people are healthier – and [religion] gives you a way of dealing with difficult problems. And these are quite significant advantages

Lots of people have tried.

I know, but nothing that impresses me. It’s so far outside of science. And yet I know some very good scientists who are deeply religious. I have several friends like that.

Do you think they believe it without any evidence?

Well, they take quite a lot of it from the Bible. I went to hear [John] Polkinghorne5British theoretical physicist, theologian and Anglican priest, whose many books include Science and Religion in Quest of Truth (SPCK, 2011) and The Faith of a Physicist: Reflections of a bottom-up thinker (Princeton University Press, 2014). He interviewed for High Profile the mathematician Sir Roger Penrose in 1999 and the Astronomer Royal Sir Martin Rees in 2005. the other evening and he was using mainly the Bible as evidence. I asked: ‘What has God done in the last two thousand years that you can point to?’ He mumbled a bit, but he didn’t have anything to offer.

I asked the Chief Rabbi the same question, and he said: ‘Well, he founded the state of Israel.’

Well, that’s just ridiculous.

You don’t think there could be evidence of Providence in history?

No, absolutely not.

How do you know this absolutely? That’s very strong.

Well, I do have strong views. I’m not an agnostic, no question about that. There’s no evidence I know of that gives even a hint of the existence of God.

What if somebody said, ‘I’ve experienced God’?

Oh, many people do have very real religious experiences – no question about it. I think there is a belief in God – well, not God specifically but mysticism or that sort of thing – hardwired into our brains. I certainly believe that. And I think that is because our ancestors who had a propensity for mysticism or religion of one sort or another did better than those who did not, and therefore they were selected.

How would a propensity for mysticism be advantageous in evolutionary terms?

Well, I think there is evidence that religious people are healthier. Also, it provides explanations for all sorts of phenomena, you know – and it gives you a way of dealing with difficult problems. If you got ill, you could pray. And these are all quite significant advantages.

So, you would account for the existence of religious belief – belief without evidence – in terms of its fitness for survival?

Absolutely.

And that would be genetically transmitted?

It would have a genetic component.

How the cell came about is just… Wow! It’s absolutely mind-blowing. It’s truly miraculous. We understand quite a lot about evolution, but the origin of life itself – that’s not solved at all

I argue this in my book Six Impossible Things before Breakfast.6Six Impossible Things before Breakfast: The evolutionary origins of belief (Faber and Faber, 2006) Scientists have now isolated the active component in magic mushrooms and if you give it to a group of people they will certainly have mystical experiences – and if they’re a bit religious they’ll have religious experiences. People who take LSD have extraordinary experiences. And it can’t be this boring molecule [that is having this effect]. The circuits have to be there.

And many people have these experiences. If you ask the public, ‘Have you had a strange experience this year?’, many have. One of my favourite books is William James’s The Varieties of Religious Experience.7First published in 1902 I think it’s a wonderful, wonderful book.

Yes, I agree. So, you have no difficulty in accepting religious experience –

No – and, as James said, it feels as real as anything else in your life. It’s not that people see this as just a mystical experience; they feel it as a real experience.

That would suggest to me that it is more normal to be a religious believer than not.

Oh, I think that’s probably true.

So, how have people like you escaped…?

It’s something I have thought about. Maybe people like me just didn’t find it that useful. I don’t have a good explanation, to be quite honest. And why has religious observance gone down so much in Britain? I think it’s partly that religion doesn’t fit that easily into the way the modern industrial world works – but you’d hardly call America a non-scientific, non-technological society and there, I don’t know, 80 or 90 per cent of people are religious.

If such experiences are very widespread, in virtually every human society –

We’d have to try and see why people believe… It’s rather like astrology and telepathy and such things.

So, that’s where you’d put religious belief, alongside such bizarre beliefs?

Yes, of course.

Does it temper that thought that most of the greatest scientists and philosophers in the past have had religious beliefs?

Oh, listen, [Isaac] Newton was deeply religious. And Galileo was religious as far as I can see. No question about it. No, I have no problem with that. But at that stage that’s the way people were. And, as I say, there are quite a lot of distinguished scientists now – Sam Berry,8Professor of genetics at University College London from 1974 to 2000, who was billed by UCL as ‘a massive figure in evolutionary and ecological genetics, biodiversity and conservation biology’ too, is deeply religious.)

And Francis Collins, the head of the Human Genome Project.9Interviewed for High Profile in March 2008

Absolutely.

You know he’s just written a book, The Language of God?10The Language of God: A scientist presents evidence for belief (Simon & Schuster, 2006) I don’t think it says anything terrifically new, but he writes that for him DNA is one of the great pieces of evidence for the existence of –

You know he’s just written a book, The Language of God?10The Language of God: A scientist presents evidence for belief (Simon & Schuster, 2006) I don’t think it says anything terrifically new, but he writes that for him DNA is one of the great pieces of evidence for the existence of –

I understand why he would take that view. Actually, it’s not the DNA that matters, it’s the cell. How the cell came about is just… Wow! It’s absolutely mind-blowing. It’s truly miraculous – almost in a religious sense. I think we understand quite a lot about evolution – although even in later evolution there are problems for which we don’t have good explanations – but the origin of life itself, the origin of the cell itself, that’s not solved at all.

And then, of course, there’s the whole problem of where the universe itself came from. And that is a great mystery. Big Bang, big schmang! How did that all happen? I haven’t got a clue. And when I say to my astronomer friends, ‘What do you think occurred before the Big Bang?’, you know, they have real problems.

So, at least we can say that science has not got all the answers…

No, it hasn’t.

Not that religion has. But at least we can’t say that science has shown that God is an impossibility.

It’s outside of science. Absolutely.

Are you happy to be described as a ‘neo-Darwinian’?

I’m afraid I would have to say that, yes.

So, even though you find it ‘miraculous’, you think we must account for the emergence of life purely in terms of random mutation and natural selection?

That’s the line we must pursue, yes.

Why ‘must’?

Because there really is no other way. Otherwise, you can only invoke God.

Yes!

And then you’ve got to explain how God came into it! And although I’m against philosophy of science and [Karl] Popper’s nonsense about falsification,11That is, that a theory is genuinely scientific only if it is possible in principle to establish that it is false. there’s nothing you could ever falsify about God creating things. No, no, the God explanation for me is just nonsense.

Would you say at least that things such as the structure of the cell are compatible with the existence of a wise Creator?

But that Creator would have to be even more extraordinary than the cell itself, and so you’re invoking something even more magical than the thing you’re trying to explain. So, I don’t find it helpful. In fact – I’m sorry to be blunt – I find it ridiculous.

No, I think that’s fair enough.

I’m curious to know how you became religious.

Oh… It goes back to those horrible philosophers, actually – Plato and Aristotle and Aquinas –

Oh, the Greeks are my heroes! I mean, all science came from them. No one else had a clue.

My subject is reductionism all the way. It’s mainly molecular stuff these days. Holism? Woof! I’m against it

– and Leibniz was quite important for me, and A N Whitehead. Together, these give you the idea of trying to find an ultimate explanation for why things should exist. To put it in a very crude nutshell, if every possible logical state was evaluated according to its goodness or badness, you would have an internal reason for the existence of any universe whose values met the requirement that it’s worth existing.

It’s very philosophical.

It is very philosophical.

So, you’ve never had a religious experience?

Ah! This is not about me. But, all right, it’s fair to say that I had an experience probably very like your son’s. But I still had to ask myself the question: Is this plausible? You know, you seem to experience a personal reality…

Listen, I have a very close friend, a highly intelligent woman, who has seen ghosts three times – and the way she knew they were ghosts is, they didn’t have feet. For her, those experiences are as real as us sitting talking here.

But you think she’s wrong?

Yes, of course I do.

You call yourself a ‘materialist’. Isn’t it difficult to be a materialist now, strictly speaking, as a scientist?

Not for me.

Is that because you’re a biologist, do you think?

Or an engineer. Probably.

I mean, I don’t want to take us both far out of our depth, but isn’t it the case that in quantum physics matter has become something extremely odd?

Yes, what you say is true. I’m out of my depth here.

Is it fair to say that in much of science there is a rising tide of what one might call ‘anti-reductionism’?

Not in my subject. My subject is reductionism all the way. It’s more and more detail, going down. It’s all about putting in this gene, putting in that gene. It’s mainly molecular stuff these days. You know, I take my anti-depressant pill and that’s a molecule that’s doing something. I don’t think that it’s going the other way. Holism! Woof! I’m against it.

I remember interviewing a Nobel-Prize-winning chemist, though, who said that you couldn’t derive chemistry from physics. Whether he’s right or not, I don’t know, but one has to be a little careful.

There’s no area that science shouldn’t go into – I believe that quite strongly. That’s my religion, I suppose: to try to understand how things work

Maurice Wilkins12One of the three biologists who in 1962 won the Nobel Prize for determining the structure of DNA once told me that strands of DNA ‘intertwine in a loving embrace’. I said, ‘That’s a very nice metaphor’ and, to my astonishment, he said: ‘That’s not a metaphor.’

Amazing. I might steal that for my book, actually. (I’m writing a book about the cell at the moment, funnily enough.)

Well, I can understand. And that our mind, you know – that all it is is a group of cells… My other son is working on motor control in Cambridge as a professor there, and it’s just amazing how the brain works. Absolutely amazing. These cells are just so clever!

Yes. Or their Creator is, perhaps. For some of us.

Now, you have said that religion is a delusion but one that is very helpful to many people. If the effect of a lot of science is to disillusion people, that may actually be generally unhelpful.

It may be.

Do you have an absolute commitment to find out the truth whatever the cost, or do you think there may be some things it is better not to know?

No, I think there is nothing it’s better not to know. I think there’s no area that science shouldn’t go into and try to understand. I believe that quite strongly. I don’t think that science turns people off religion.

But why do you have such an absolute commitment? Why is it better to know the truth than to be happy, say, if finding out the truth actually disillusions you?

Oh, I see! Because you don’t know what you’re going to find out. Because you really want to understand how the world works. It’s better to know. A lot of people have said we shouldn’t look at genetics too much – we might find that Jews are much cleverer, that people from Oxford tend to be rather religious… Well, if that’s the way it is, that’s the way it is – and we need to understand how the world is.

What you do with it is another matter. I always say that you don’t need science to do terrible things. It’s what you do with your knowledge that matters and I claim that science is ethics- and value-free. It’s the way the world is.

Although the ultimate paradox is that that commitment to truth is the biggest value there is.

Yes, I suppose it is. That’s my religion, I suppose: to try to understand how things work.

This edit was originally published in the March 2007 issue of Third Way.

To make sure you hear of future interviews in this series, follow High Profiles on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

| ⇑1 | See researchamerica.org/advocacy-action. |

|---|---|

| ⇑2 | Interviewed for High Profile in February 1995 |

| ⇑3 | ‘When anyone tells me, that he saw a dead man restored to life, I immediately consider with myself, whether it be more probable, that this person should either deceive or be deceived, or that the fact, which he relates, should really have happened. I weigh the one miracle against the other; and according to the superiority, which I discover, I pronounce my decision, and always reject the greater miracle’ (An Enquiry concerning Human Understanding, 1748). |

| ⇑4 | String theories propose that ultimately matter is composed not of particles but of strings, whose vibrations give them the appearance of the different kinds of particles physicists have observed. These theories seem to go some way towards explaining and reconciling the four fundamental forces in nature – electromagnetism, the strong and the weak nuclear force and gravity – but they also seem to require the existence of (maybe many) more dimensions than we experience. |

| ⇑5 | British theoretical physicist, theologian and Anglican priest, whose many books include Science and Religion in Quest of Truth (SPCK, 2011) and The Faith of a Physicist: Reflections of a bottom-up thinker (Princeton University Press, 2014). He interviewed for High Profile the mathematician Sir Roger Penrose in 1999 and the Astronomer Royal Sir Martin Rees in 2005. |

| ⇑6 | Six Impossible Things before Breakfast: The evolutionary origins of belief (Faber and Faber, 2006) |

| ⇑7 | First published in 1902 |

| ⇑8 | Professor of genetics at University College London from 1974 to 2000, who was billed by UCL as ‘a massive figure in evolutionary and ecological genetics, biodiversity and conservation biology’ |

| ⇑9 | Interviewed for High Profile in March 2008 |

| ⇑10 | The Language of God: A scientist presents evidence for belief (Simon & Schuster, 2006) |

| ⇑11 | That is, that a theory is genuinely scientific only if it is possible in principle to establish that it is false. |

| ⇑12 | One of the three biologists who in 1962 won the Nobel Prize for determining the structure of DNA |

To find out more about the agenda behind our interviews, read our manifesto. To access our archive of more than 260 interviews, see the full list.

Biography

Lewis Wolpert was born in 1929 and was educated at King Edward’s School, Johannesburg. He studied civil engineering at the University of Witwatersrand.

In 1951–52, he was personal assistant to the director of the Building Research Institute in Pretoria, before hitchhiking to Israel, where he worked for a year for the national water planning department.

He migrated to Britain in 1954 and did a course on soil mechanics at Imperial College, London before switching to studying the mechanics of cell biology at King’s College London, where he gained his doctorate in 1960.

He lectured in zoology at KCL from 1958 until 1966, when he was appointed professor of biology as applied to medicine at Middlesex Hospital Medical School. In 1987, his department was merged with the department of anatomy and developmental biology at University College London. He finally retired from UCL in 2004.

He was a fellow of Imperial College from 1996 and of KCL from 2001.

He sat on the Cell Board of the Medical Research Council from 1982 to 1988 (from 1984 as chair) and on the MRC itself from 1984 to 1988. He also chaired the EEC’s Biology Concerted Action Committee (1988–91) and the Committee on the Public Understanding of Science (1994–98), and was president of the British Society for Cell Biology from 1985 to 1991.

He lectured in universities around the world, and gave the Royal Institution’s Christmas Lectures in 1986 and the Royal Society’s Medawar Lecture in 1998.

He presented Antenna on BBC2 in 1987/88. On BBC Radio 3, from 1981 he conducted interviews of many other leading scientists (which, with Alison Richards, he edited for publication as A Passion for Science in 1988 and Passionate Minds in 1997), and also presented two documentaries: The Dark Lady of DNA (1989) and The Virgin Fathers of the Calculus (1991).

He was the author of Triumph of the Embryo (1991); The Unnatural Nature of Science (1992); Principles of Development (1998); Malignant Sadness (1999), which was turned into a three-part series, A Living Hell, which he presented that same year on BBC2; and Six Impossible Things before Breakfast (2006).

He was a member of the American Philosophical Society and of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was made an honorary member of the Royal College of Physicians in 1986, and an honorary fellow of UCL in 1995. He received the Scientific Medal of the Zoological Society in 1968, the Michael Faraday Award in 2000 and the Hamburger Award of the American Society of Developmental Biology in 2003.

He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1980 and of the Royal Society of Literature in 1999, and received honorary doctorates from the CNAA, the Open University and the Universities of Bath, Leicester and Westminster.

He was appointed a CBE in 1990.

He married in 1961 and had two sons and two daughters.

Up-to-date as at 1 February 2007