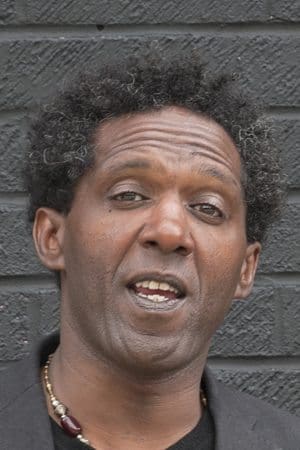

Lemn Sissay

was long established as a poet and playwright when in 2015 Desert Island Discs brought the pain of his past to the attention of millions.

Martin Wroe talked to him in the East End of London on 15 July and at the Greenbelt Festival on 27 August 2016, and found him accentuating the positive.

Photography: Andrew Firth

When did you first know you were a poet?

I was born to be the poet that I am and I knew it very early on, when I was about 12 years of age. I went through my schooling knowing that I would be a poet at the end of it. The only way I knew how to understand the world was through the books I’d read as a child, which was the Bible, basically, and books about the Bible; and so I only understood the world through symbolism. That was the only way my [foster] parents taught me how to understand the world, and so that was the only way I could translate my experience.

By the way, I’m making that connection now, looking back. It’s been a long journey to admit that those great writings that have influenced so many people around the world must have influenced me. It wasn’t a good upbringing and it wasn’t generous or pretty. They wanted it to be kind and it wasn’t, it was brutal.

You were taken from your Ethiopian birth mother when you were two months old and given to a white, Christian family in a village in Lancashire, is that right?

When my mum came to this country, she [wanted to have] me fostered for a short period of time while she studied. The social worker gave me to foster parents who were looking to adopt and said to them: ‘Treat this as an adoption. We’ll get her to sign the papers. His name is Norman.’ I was with them for 12 years. They were going to make me into a missionary so that I could go back to Africa and save all the poor black babies.

And then you left them –

They left me! The story was that I ran away from them, because I didn’t want to be with them; and it took me 15 years to work out that they made that choice. They said that it was my choice to leave them – that was the cruellest thing they did. They told my brothers, my sisters, my aunts, my uncles, my cousins, my grandad, my grandma, all my friends in the town, not ‘We’ve got rid of him’ but ‘He’s left us. Don’t contact him!’ And none of them did.

The Guardian said: ‘Lemn Sissay has Success written all over his forehead’ – and I knew that was a curse to me, because every time I was recognised [as a poet] I recognised what I didn’t have: unconditional love

Did their faith have any bearing on their decision?

They thought the devil was inside of me. They did the thing in the front room where they put their hands on my head and they were like: ‘Cast the devil out of this boy!’…

They thought you were possessed?

I find it difficult to imagine that they thought I was possessed, but they did say that the devil was working inside of me. If you believe in God and the devil and you’re going to have God influencing things, you’ve got to have the devil [influencing things, too].

What led them to that conclusion?

I was entering adolescence and I was smoking cigarettes and staying out late with my friends and taking biscuits from the tin without saying ‘please’ or ‘thank you’. That was as bad as my evilness got, but they’d never had an adolescent before, so they were like: ‘He’s lying to us! Who is he?’ My [foster] mum actually was saying: ‘We don’t know who your father is or where you’re from.’ That was the most poisonous thing, to leave a child with that thought. You don’t know what you’re going to become.

What happened to you then?

The [care system] then held me for six years in four different children’s homes. The last one was a virtual prison – they couldn’t put me in [an actual] prison because I hadn’t done anything wrong – and I was there for 10 months. And [when I reached 18,] I left the Wood End Assessment Centre (which is now being investigated by the police for abuse by staff)1See bit.ly/2cyVEKD. and I was given my birth certificate and that was it.

I’m not angry, by the way. I genuinely am not.

When I left the care system, the whole idea was that I’d prove them right. Society believed that I would prove them right and my brain was set to prove them right. That’s the power of suggestion. In a family, it’s ‘When are you going to university? When are you getting married?’ For me, it was: ‘There’s nothing good’s going to come of that kid. Nothing good…’ So, I was left to deteriorate.

But instead you published a collection of poems, Tender Fingers in a Clenched Fist…2Bogle-L’ouverture Publications, 1988

By the age of 21, the Guardian was saying: ‘Lemn Sissay has success written all over his forehead’ – and I knew that was a curse to me, because every time I was recognised [as a poet] I recognised what I didn’t have. There was no unconditional love.

You’ve spent much of the last 30 years going back over your childhood…

When I left care, I was like: I don’t have a story, I don’t have anybody to tell me my story – I mean, this is big, you know? And I couldn’t communicate it to anybody else because they had stories and the whole idea of having a story is that you don’t know what it’s like to not have one. When you tell somebody you’ve not got a family, the first thing they’ll say to you is: ‘Bloody hell, families are not all good, Lemn!’ Do you know what I mean? They cannot imagine what it’s like not to have one.

From the age of 18, I used all my resources to prove what happened to me as a child. It’s been a massive mission that people only understood fully [in October 2015 when I was on BBC Radio 4’s] Desert Island Discs.3Download from bbc.co.uk/programmes/b06gthsz. That’s how people got it.

And it turned out that you’ve got one of the most extraordinary stories. Everyone thought: This is so moving!

Absolutely. Absolutely. But I had to fight to get the evidence to be able to tell that story. You know, ‘Going back to your roots, is it, Lemn?’ No! I had nobody, you know?

I think poetry is where the true you is revealed. I think poetry talks to the true self. You can see a person in their poems – and it’s as much about what they don’t talk about as what they do

So, I had to find evidence – I was like a detective. The moment I left the care system, I had to go back. And they were like: You’re not coming back, you’re not going to see your files, you shouldn’t be here. I was literally like, ‘My God, you want me to go mad! You actually are concocting the ingredients for my internal explosion.’ And I never said that was OK. My poetry was a kind of evidence that I never settled for it.

Does it frustrate you that you get asked about your background rather than your poetry?

Ah, no! They have both served each other magnificently and miraculously.

One thing you learn as a growing artist is that it’s your story, it’s nobody else’s. Your journey, artistically and personally, is yours – you’re not in competition with anybody, you know.

I’ve had to be really focused to do what I’ve done regarding my family, and in many ways I think that my artistic journey has… I don’t… I do feel that I will be a good writer one day. I feel like, you know, my story has taken up a lot of time. I have no problem sharing it with people, and in fact the investigation of it, and the documenting of it, has been the most important thing that’s happened in my adult life.

As a teenager in the care system, you’ve said that poetry became a kind of refuge, a way of translating the world.

That’s right, yeah. I was in a system that was telling me what I was without using words, and I knew it wasn’t true. So, I found in poetry, like, a more fluid yet solid acknowledgement of who I was, and what the world around me was as well. I didn’t believe the people who were around me. I didn’t believe that they cared as they should have done and therefore I didn’t believe that their reflection of me was anything other than an untruth. And I felt very unsafe in that environment and poetry allowed me to investigate who I was, who they were, what the world was, from a very compassionate, empathetic and yet frightened place.

And poetry was a ‘place’ you could rely on?

As an interpreter of my spirit and of the strange energies that were having a physical and emotional impact on my day-to-day, minute-to-minute life.

This is why my poems are like my family. Through memory, family is consistently translating itself in the world, and arguing about the meaning of words, or a symbol or an image, and I realised when I left care that nobody I knew had known me for longer than a year. So, it meant that memory just fell through the sieve – nothing could hold – because to have a good memory of your life in family you have to have two people to at least argue about it. And I realised the depth of that by not having it, and I would not wish that on my worst enemy. You are supposed to learn about that as people die as you get older, but I knew about that at 18.

Family’s like a game of squash: you hit the ball and it comes back at all kinds of awkward angles [and that gives you exercise]. But when I left care the image that I had was of hitting the ball and it just continuing to fly out and my muscles wasting and there being nothing I could do about that. So, I was fully aware of what I didn’t have and I was fully aware that those other 18-year-olds around me hadn’t as yet got to a point where they could understand what I didn’t have. But I realised what I didn’t have, and the vastness of it. It’s not that I think that families are good, it’s that I just wanted someone to argue with.

It was like you didn’t have a witness?

Thank you! That’s it! I didn’t have a witness. In the children’s homes all the people would do was try to solve you as a problem, do you know what I mean? ‘Right, what are we doing with him now? He needs fostering, he needs this, he needs that.’ And I was like: No, that’s not it. You weren’t here a year ago, were you? So, you’re trying to solve me now and I don’t need solving, I need seeing.

So, in our families we have memories, we have anecdotes, we have arguments –

We fall out, we separate – very important!

– but someone in your situation ends up instead with case notes.

That’s right – which I’m not allowed to see. Over 18 years of case notes.

And they’re a dispassionate record from some professional –

Who’s watching me like it’s an experiment…

[But] poetry made me feel alive and I came to realise that the imagination was an incredible landscape that would unfold the more I walked into it.

You have said that poetry is ‘the voice at the back of the mind’. It’s a great phrase.

I think that we think in poetry and we try to order our thoughts to communicate to each other in inadequate sentences. I think poetry is where the true you is revealed. I think poetry talks to the true self. You can see a person in their poems – and it’s as much about what they don’t talk about as what they do.

It’s a beautiful thing, sometimes, to be with your poems. It’s like being with your gang. They are very – very empowering; and you have a responsibility to them. I’m really nervous about them going out in my new book4Gold from the Stone: New and selected poems, published by Canongate on 25 August 2016 and everybody being able to pore over them, just as you would feel nervous about somebody poring over your kids.

Some of your poems – I’m thinking especially of ‘Let There Be Peace’5bit.ly/2cdyUVt – are almost like beatitudes. They’re like a welcome to the world that could be.

I love reading that poem and asking people to join in at the end. Somebody wrote a review of it online that says, ‘It’s a great poem, blah blah blah, ruined by the last line’; and it’s really interesting, I’ve always wanted to take that line out of the written form but whenever I read it and I hear a whole audience joining in at the end with the ‘Shhhhhhhhhhhhhh’, it sounds like the sea and it’s beautiful!

I saw a comment on that poem online that said: ‘You are truly anointing the arts from head to toe.’ Do you ever feel like you’re anointed?

‘Yes’ is the real, true answer.

Sometimes people have linked the poet and the shaman. Is there any truth in that?

There are times, yeah, when you really do get lifted and you know magic is happening. I mean, the shaman is as much a trickster as anything else, but it’s amazing when you become possessed by a poem. Oh, my God! It doesn’t happen a lot but when it does, it makes people think: ‘Is he OK? What’s going on?’ And I like that. I like an audience to feel like they need a shower after a gig. ‘What the fuck is this?’ I like to feel like I’ve had an experience, you know what I mean?

You are mesmerising when you perform your poetry – you kind of animate your own words. What happens to a poem when you perform it?

The way to read poetry on stage, always for me, is to inhabit as much as you can the time that you were writing the poetry. In other words, do it like you believe it.

So, I’m not intimidated by an audience. The beauty of being able to share a poem with an audience is that it’s like being able to share your greatest gift. How would I be intimidated by an audience when I’m with something which is just so important to me that it is beyond any acceptance or rejection of any person ever? Now, that can be a bit nauseating for an audience, because I’m in my own zone; but I’m afraid that’s who I am and that’s what I’ve done for some 30 years.

You know, my poems are my friends and my family and they talk back to me and they have personalities of their own and every time I read them they’re slightly different for me, so it’s like the first time every time.

Does a poem ever say, ‘I don’t want to be like this’?

Oh God, are you kidding me? Yes, they do. They can be angry with me for not giving them the care and the attention, some of them, that they deserve.

I’m saying all of this out loud, aren’t I, I really am – but that’s the truth!

I believe that God is in everybody and I feel so blessed to have got to that point, because before that I couldn’t forgive anybody. I am amazed that I have got to where I’ve got to

The famous maxim is that a poem is never finished, it’s only ever abandoned.

Well, yes, it is – but so’s everything.

Listening to Desert Island Discs, I was very moved by the way you said you were able to forgive your foster mother.

They believed they were doing the right thing. You know, they were naive. I know that they had a child by accident and my mother had post-natal depression and it was putting pressure on the family. They’re not horrible people. They’re good people. I can say that now with true clarity, because when I did [eventually] forgive my mum she said: ‘Oh, I can breathe again!’ She meant it.

I hadn’t realised she was bothered. Long after Desert Island Discs had gone out, I called her up to say, you know, ‘You can hear my story.’ And, it was really sad, she said: ‘I can’t, Lemn. I can’t. I can’t hear it.’ And I thought: My God! They created this narrative early on in my life and I should have justified that narrative by becoming bad in some way – and I didn’t. So, the more my star shone, the more it must have hurt them. I realised then that they were suffering.

In the Anglican Prayer Book of New Zealand, after the confession the priest says these words of absolution: ‘God forgives you. Forgive yourself. Forgive others.’

That’s beautiful!

What about your own faith? Somewhere you have said there was a period when you didn’t believe and then later you found yourself coming back to a sense of –

Yeah, yeah. I could not – I could not see God because he represented everything that they’d done to me. And now I don’t have religion but I believe in God. I believe that God is in everybody and I feel so blessed to have got to that point, because before that I couldn’t forgive anybody. I couldn’t forgive anybody. I couldn’t form friendships. I mean, I am amazed that I have got to where I’ve got to, spiritually and what have you. The moment I accepted, a few years ago, that there is a Power greater than myself and that it can be believed in, the world just opened up!

I think you can be a great achiever, you can have great insights into the world, you can be a mover and shaker – you know, I’ve got a lot of form, I’ve done a lot of stuff – but none of it gets close to truly asking a higher Power for help. None of it gets close to that.

It’s very difficult to speak about.

It sounds as if you had a spiritual awakening that enabled you to forgive and that released you.

That’s right. So true. You know, their religion was all about forgiveness and I was like: You can’t send some bloody emissary called ‘God’ to say, ‘Go on, forgive them!’ You can’t do that. You’ve got to ask me personally. What I didn’t know was how releasing forgiveness is! I had no concept that in doing it, like, it would kind of change my life. True forgiveness is just amazing!

I understand that recently three other people asked you to forgive them…

I met with Lord Peter Smith, the leader of Wigan [Metropolitan Borough] Council, its chief executive and the head of children’s services. Some years ago, Lord Smith said in the House of Lords: ‘Apparently, there’s a young man who was brought up in our Wigan, his name’s Lemn Sissay, he’s done a Ted talk6See bit.ly/2cY65h5. and I suggest that you view it.’ What he didn’t [remember] is that he was the finance guy at the council when I left at 18 years of age, when my social worker asked for something for my carpets or curtains or a cooker and the head of children’s services said: ‘This boy’s not going to get a penny of our money.’

And all three of them met me in Manchester Town Hall and gave me an unequivocal apology. They pushed the table back and we sat in a circle and they said, each one of them, ‘We are sorry. We are sorry for everything that we’ve done to you.’

Can you talk about your search for your biological family?

My father was a pilot for Ethiopian Airlines. He died in a plane crash in 1973 and I found his plane in the Simien Mountains, between Eritrea and Ethiopia. And I found his family. His brothers and sisters were lecturers at Berkeley, Harvard etc – I’ve got an aunt who was the head of gender studies at [the University of Massachusetts Amherst].

My mother went on to marry the vice minister of finance under the Emperor Haile Selassie, and I found her side of the family all over the world. When I found my mother, I looked exactly like my dad the last time she saw him and she didn’t see me, she saw him and I realised it wasn’t about me, it was about her and I realised that it would take a lot of work for her to be able to be close to me. So, it never really happened. It took my mum eight or nine years to tell me my dad’s name.

She works for the United Nations and for most of those years she kept disappearing and I would have to find her again. I found myself stalking my own mother and I had to write to her to say: ‘If you don’t want me to find you, you have to tell me, because I’ve earned that right. But if you tell me, I won’t look for you.’ And she disappeared again.

My name ‘Lemn’ means ‘Why?’ in Amharic. There’s only one person with my name in the world. Why would a 21-year-old woman [in the north of England] name her child ‘Why?’? In Ethiopia, people stop me on the street and say ‘Lemn’. They can’t believe that I’d turn around to a question!

I get why my [birth] mum wouldn’t talk to me, I get why my brothers and sisters couldn’t communicate with me and I get why my family would really prefer me to shut up. I am a living, breathing question that causes distress to the family that I spent my life searching for. Ninety-nine per cent of them will not speak to me. Even the person that gave me that name. All I can say is that [when I learnt this] by email, in the most horrible, hurtful way, I then realised that I had a family and I knew what that meant and I could let it go.

What does Ethiopia mean to you?

Ethiopia is an incredible place. What can I say? I am now known and accepted in Ethiopia. I’m accepted by my people, I’m loved, genuinely loved – and for that to have happened through poetry is just incredible. If I walk the streets of Addis Ababa, people will stop me. When I went to Lalibela to see the [rock-hewn] churches, the boy who was showing me around said he’d heard of a poet from England who’s Ethiopian and I was able to say it was me!

Nowadays, you live in London. You sometimes say you have no home, but then you say that your head is in London, your heart is in Manchester and your soul is in Addis Ababa. So, where do you feel that you come from?

Well, I come from all of those places and none of them, you know. That’s just the way it is. And I’m OK with that. I mean, I’m kind of starting to be OK with it. I’ve come to understand that it’s important to be at home wherever you are. There’s nowhere to go back to. And I don’t feel that’s a loss. I can’t lose what I’ve never had.

Home is wherever you are now?

Yeah, as best as I can make it. I mean, that’s where we all want to be, isn’t it?

You know, the alternative narrative is ‘I have no this, I have no that. I didn’t have this and I didn’t have that.’ All of which is true. We get locked into an idea of what we should have been, and that will always lead to depression and anxiety and dissatisfaction. Self-acceptance is really profoundly important.

And, also, the less you have, the more important it becomes.

So, life is an improvisation?

Yeah, it really is. In many ways, that is what we fear most, that we may have to improvise [when] the family isn’t there. Well, for me it never was, you know? So, the idea of improvising is to find not just that you’re coping with the present but that there is real magic in whatever the alternative is. Real, true, powerful, profound magic.

Material from Martin Wroe’s conversation with Lemn Sissay at the Greenbelt Festival is included with kind permission from the Festival.

To make sure you hear of future interviews in this series, follow High Profiles on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

| ⇑1 | See bit.ly/2cyVEKD. |

|---|---|

| ⇑2 | Bogle-L’ouverture Publications, 1988 |

| ⇑3 | Download from bbc.co.uk/programmes/b06gthsz. |

| ⇑4 | Gold from the Stone: New and selected poems, published by Canongate on 25 August 2016 |

| ⇑5 | bit.ly/2cdyUVt |

| ⇑6 | See bit.ly/2cY65h5. |

To find out more about the agenda behind our interviews, read our manifesto. To access our archive of more than 260 interviews, see the full list.

Biography

Lemn Sissay was born in the village of Billinge, near Wigan, in 1967 to an Ethiopian mother. He was brought up by foster parents as Norman Greenwood and was put into the first of four children’s homes in Greater Manchester in 1979. He left school at 15 with one GCSE and two CSEs. He spent 10 months in Wood End Assessment Centre in 1984.

When he finally left the care system, he was given his birth certificate and a letter written by his mother in 1968 pleading for his return. He resumed his real name and began searching for her. He finally met her in 1988 in the Gambia.

In 1986, he got a job as a literature development worker at Commonword, a community publishing co-operative in Manchester for which he set up Cultureword.

Two years later, he published his first book of poetry, Tender Fingers in a Clenched Fist. He has been a full-time writer and performer since 1991. His subsequent books are Rebel without Applause (1992), Morning Breaks in the Elevator (1999), The Emperor’s Watchmaker (2000), Listener (2008) and Gold from the Stone: New and selected poems (2016). He also edited the poetry collection The Fire People (1998).

His ‘landmark poems’ are engraved at sites across Manchester and London, including at the Royal Festival Hall, the Olympic Park and Fen Court, where ‘Guilt of Cain’ was unveiled by Desmond Tutu in 2008.

He has written seven plays: Skeletons in the Cupboard and Don’t Look Down (both 1993), Chaos by Design (1994), Storm (2002), Something Dark (2006), Why I Don’t Hate White People (2011) and Refugee Boy (2013), which is an adaptation of the novel by Benjamin Zephaniah.

In 1995, he made Internal Flight, a documentary about his life, for BBC2.

He was an artist-in-residence at the Southbank Centre in London from 2007 to 2013 and is now an associate artist.

He was the official poet of the London Olympics in 2012.

In 2015, he was elected chancellor of Manchester University for seven years by the university’s staff and registered alumni and members of its general assembly.

He has honorary doctorates from the Universities of Huddersfield (which since 2010 has offered a Lemn Sissay PhD Scholarship for ‘care leavers’) and Manchester.

He was appointed an MBE in 2010 ‘for services to literature’.

He is a patron of the Letterbox Club and The Reader, a trustee of World Book Night and a ‘celebrity ambassador’ for BookTrust. He was the Coram Fellow of the Foundling Museum in 2014–15.

Up-to-date as at 1 September 2016