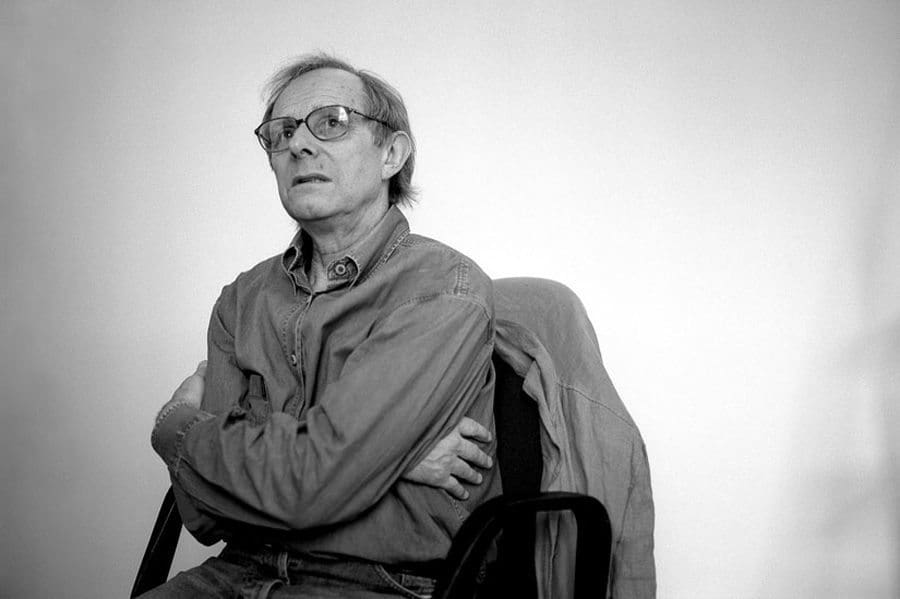

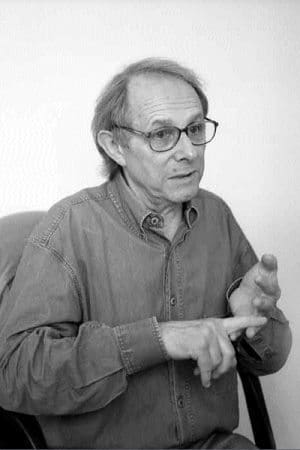

Ken Loach

is recognised across Europe as one of Britain’s greatest living filmmakers.

Nick Thorpe met him on 18 July 2002 in the offices of Sixteen Films (four years before he won the first of his two Palmes d’Or at Cannes and received a Bafta Fellowship).

Photography: Andrew Firth

Your films often portray childhood as a traumatic time. Can you tell us a little about your own upbringing, and how it shaped your values?

I grew up in the Forties and Fifties, in a small town in the Midlands. People now would think it was quite boring, but in fact from a child’s point of view it was the opposite: I had all the benefits of growing up – after the war, which was obviously a big upheaval for everybody – in a comparatively placid, stable and secure world.

Was there any radicalism in your background?

No, by no means. I didn’t really get involved in anything remotely political until after I’d left university and I was mixing with writers and friends who were in television and film, starting to read, going to meetings – going through the experience of working for Harold Wilson’s election and then seeing what happened. Going through all that in the Sixties was what my politics sprang from.

Did you come from a middle-class family?

No. My father’s family were miners and he was an electrician who worked in a machine-tool factory. But he was a very shrewd man, and a very strong personality, actually, and he became a foreman and was given added responsibilities. So, I guess my parents would think of themselves as lower-middle-class. I actually think he was working-class, but it’s one of those shades of class classification which is interesting but a little bit arcane.

Did the church play any part in your formation?

I went to church for about a year, I think, in my teens: it was a place to meet girls (you see how hard-done-by we were in Nuneaton!). Then I just ceased to go. My mother used to go to church, infrequently, but it wasn’t a particularly religious upbringing.

I would describe myself as an agnostic with atheist tendencies. In England, the church has traditionally been a bulwark of the established order. It’s defended the rights of property and, apart from liberation theology, it’s been a very strong force for reaction.

You must have seen the church in different guises – for example, when you were filming Carla’s Song.

Yes, well, there were several priests in Nicaragua involved in the Sandinista leadership1Notably, Miguel d’Escoto served for many years as foreign minister, Fernando Cardenal as minister of education and Ernesto Cardenal as minister of culture. and they were obviously playing a very progressive role. But the essence of religion – belief in an afterlife and a god, or several gods – seems to me irrational, and I think it becomes an excuse.

I think we should all be much tougher in scrutinising religious beliefs. I mean, it’s epitomised by ‘Thought for the Day’ on Radio 4. For the two or three hours surrounding that, anybody who asserts something will be scrutinised, quite properly, but the moment somebody invokes their religion, everybody backs off. I think that’s absolutely wrong. We should question everything and ask for the evidence, and if it doesn’t stack up we don’t accept it. We should apply the same rigour to religious belief as we do to any other proposition, scientific or legal or whatever. Then, I think, the humbug and cant would disappear.

We should apply the same rigour to religious belief as to any other proposition. Then, I think, the humbug and cant would disappear

You owe it to your own dignity as a person not to have any areas where you’re afraid to use your own rational judgement. There’s an old hymn with the line ‘Blind disbelief is bound to err’ and as a kid I always used to think, ‘Well, why not “Blind belief is bound to err”?’ But blind belief equals faith and that was sacrosanct: we weren’t supposed to question that. I suppose I’m bloody-minded enough to want to question everything.

Have you ever met a Christian you admired, or are your heroes only secular figures?

I tend not to think of heroes particularly. I’m sure I could if I thought long enough. ‘Unhappy the land that needs heroes’…

Obviously, anybody who goes to the stake for what they believe, whether it’s Latimer and Ridley or the Catholic martyrs, you have to admire their courage and their steadfastness; but it doesn’t necessarily mean you have to endorse their cause.

Maybe our desire for heroes is part of the problem. Certainly in your films there is a sense that change comes from within a community, from people power, rather than from a pedestal outside. Is that fair?

Yes, I think the more you respect your own power to make judgements and evaluate what’s in front of you and decide on a course of action, the less you need hero figures to defer to. I mean, that’s one of the problems with monarchy, isn’t it, that it’s these wealthy and often rather stupid people that are the people we’re expected to applaud and look up to. Even if they were intelligent, it would make it no better. This sense of hierarchy is deeply unpleasant.

You have said: ‘One hopes to God that the cinema has no effect whatsoever, because if it does we’re all screwed.’ What then is your mission (assuming you have one) in making films?

I wouldn’t call it a mission at all. It’s just what I do, really – I just work in a collaboration with writers. To call it a mission would be terribly aggrandising.

I think what you’re trying to do is to find stories that have some significance just beyond the narrative. You can tell the story and be absolutely true to the characters in it, and maybe when you’ve told it it has implications that are wider, that shed a light on the human condition in some way.

There was a particularly strong reaction in 1966 to Cathy Come Home. Did that not convince you that filmmaking can have an effect?

Oddly enough, it was almost the reverse. It made quite a splash – it was difficult for us to imagine us ever doing anything that would have a bigger impact: it was discussed endlessly, there was this small change in the law, it coincided with the founding of Shelter and there was a big buzz about it – but the way the establishment absorbed it… Do you know the phrase ‘repressive tolerance’? Somehow it all gets smothered in this bear-hug of approbation, so that the energy of it is dissipated by people claiming it as their own and patting you on the head and saying what an excellent contribution you’ve made – and of course they don’t take it on board at all.

What we should have done was, we should have questioned the ownership of the land and the building industry, and the relationship between unemployment and housing. Homelessness is a feature of an unplanned economy, where work and housing and everything are open to the market and so you get this great disparity – some people have two or three homes, some people have none. We didn’t ask any of those big questions and so [the film] was loudly approved of and its energy dissipated.

The working class is the most powerful force in the world. It’s a question of organisation and leadership – those two things that really intrigue me and the writers I’ve worked with

There are endless examples of things like that. We did a film called Hidden Agenda about the corrupting effect of the British presence in Ireland and the way the security services were out of control – there has just been a Panorama about that and they showed quite conclusively that there was collusion between the British Army and loyalist paramilitaries and the intelligence services in the execution of leading republicans. But somehow it makes no impact at all: there’s no outrage, no one follows it up. You say, ‘It’s shocking’ and then there’s silence. I think that’s how they deal with it. That’s how they dealt with the problems of Cathy Come Home.

How does a radical voice get heard in our society?

I think the most we can do, in the general noise that is the public debate, is to try and be one still, small voice (to use a biblical phrase) in the constant flow of media trash. You don’t have any grand illusions about what you can do.

Many of your characters start out as idealists but gradually their idealism is eroded. How do you yourself keep the inner fire burning?

Well, it’s not difficult, because your observation of what is happening day-to-day just constantly feeds your outrage. The best way to get your blood pressure up is to listen to the Today programme for an hour in the morning and you emerge rampaging through the streets with rage at what’s going on and the people who are getting away with things.

And then when you do meet people who really are on the front line, who really are engaged in the struggle, their courage and determination are endlessly inspiring.

At least two of your films, Bread and Roses and The Navigators, deal with the erosion of workers’ rights. Currently in this country we are seeing (apparently) a resurgence of strike action. Does that fill you with hope or despair?

Actually, it’s hope. That is the best news. Take the [2002] Tube strike, for example. The effect on the railways of privatisation was catastrophic, and a major aspect of that was safety – there are railwaymen who won’t use their free passes because they know the rails aren’t safe. Now, if before privatisation they had said, ‘Look, this is not safe. It’s going to result in people being killed’ and had come out on strike over it, just think what we would have been spared! And if the Tube workers came out and said, ‘We’re shutting the system down indefinitely until you abandon this daft idea of privatisation and really invest in the structure and make it safe,’ if they would do that, it would be terrific. And they would win.

And yet the response of the general public is usually to protest about the inconvenience strikes cause.

Well, because newspapers are run by large corporations that are fundamentally hostile to the unions. The Evening Standard today has got a huge picture of the rail union leader on its front page that makes him look as ridiculous as they can (and you can make anyone look ridiculous in a photograph), and blames him for the cost. Of course there’ll be that – but we’ve got to be strong to resist that.

But against the huge opposition of multinational business what hope is there for change?

The multinationals are big forces, you’re right, but the working class is also a huge force: to use the old phrases, nothing is made unless a worker makes it, nothing is transported unless a worker transports it, nothing is in the shops without workers selling it, there are no services without workers to provide them. The working class is the most powerful force in the world – it’s a question of organisation and leadership (those two things that really intrigue me and the writers I’ve worked with). In the balance of class forces, the working class has huge power; it’s just it’s never been galvanised or made coherent.

And do you see any prospect of that happening?

And do you see any prospect of that happening?

I don’t know. Who knows? I think it ebbs and flows and at the moment people feel they’ve had enough of privatisation and they will fight back. Hence the shift to the left in the union leadership recently.

Some people rather glibly categorise your style of cinema as ‘uncompromising’. Is that how you see it?

I don’t know. People say that from the outside, but when you’re working on a particular film you just start from scratch and say, ‘How can we make this true? How can we go as deep as we can and really test everything all the way through?’

Films such as Erin Brockovich, or even Brassed Off and The Full Monty, covered some similar ground to your own work but gained a wider audience, arguably because they did make some compromises. Are you ever tempted to go down that road?

No, not really. It’s not interesting to me. You might sit in an office in Soho and think, ‘We really want to make this film popular. We’ll put so-and-so in the main part,’ but then you meet the real people who are the subject of the film and you see how interesting and extraordinary and specific they are and then you think, ‘This person we thought of casting is going to annihilate all that,’ because they wouldn’t be any of those things, they don’t have the quality that drew you to the subject in the first place.

So, in the end you look at the reality and think: ‘I have to do justice to that.’ That is what’s interesting and that, ultimately, is your responsibility as a filmmaker, to be true to the core idea, whatever it is.

You titled a recent film Bread and Roses –

It was an old union slogan from the US: ‘We want bread, and roses too.’

Does it depress you that, when it comes to cinema, we are still, very often, talking about bread and circuses? Many of the sort of people you portray in your films would rather watch Spider-Man.

They may well. But I think that’s the way cinema has grown up here. It has never had the breadth here that it’s had in some European countries. Think of French or Italian film, the great neo-realist films of the Fifties and Sixties. European cinema has had a much stronger intellectual and social content, and it’s taken as seriously as theatre.

Is that largely the fault of the United States?

Our cinema has always been colonised by the Americans. They think we speak their language and so we’re seen as like an outpost of their cinema, so it’s much more difficult for an independent indigenous cinema to thrive. Somebody may do two or three good films, and then people come along and wave fat cheques and they see that ‘progress’ is going to America. It’s a form of colonisation, isn’t it?

Many of your films feature a high degree of violence, whether personal or institutional. I wonder what your concept of evil is – whether that violence is the fault of the perpetrator or a consequence of the system.

I think ‘evil’ is a confusing word, really. People do bad things, or bad things happen, there will be destructive, violent tendencies and movements and events; but history is cause and effect, isn’t it? Everything comes from somewhere. So, to talk about evil as an abstraction I think is not helpful.

Would it be true to say that in your films, and especially the ones about family life, you are trying to understand a little more and condemn a little less?

Well, no. You condemn Fascism, obviously, and the works of Margaret Thatcher… But condemning individual actions (though you might condemn the action itself, or the effect it has) is not terribly constructive. The point, again, is to understand where the behaviour comes from: what prompts it, what is its motivation?

Are repentance and forgiveness concepts you find attractive or are they a distraction?

I think that what sustains you is a sense of politics. It’s only if you don’t have that perspective that you have illusions and therefore are disappointed

Well, before you can forgive anybody, if someone has done something bad to you, or been negligent or whatever… I think it’s about understanding – where they come from, where their act comes from. Then one might be able to forgive.

To take an extreme case: think of the republicans or nationalists in the north of Ireland. Before they could forgive the loyalists and unionists, those people would have to acknowledge that they went to Ireland to govern the native Irish on behalf of the British and have oppressed them for three or four hundred years, and have continued to do so until the present day. Now, if I were an Irish nationalist I could not begin to forgive those people until that was acknowledged, because I do believe in the old saying ‘No justice, no peace’ – and forgiveness, I guess, is part of peace.

A lot of your films are concerned with the rights of individuals. What, in your worldview, are such rights built on?

You take it as a given that all men are born equal. You know the old slogan from the Peasants’ Revolt:

When Adam delved and Eve span,

who was then the gentleman?

I think that’s good enough, really.

Are you at heart an optimist or a pessimist? Many of your films make the audience laugh and cry.

An optimist, I think, because people make you optimistic: some people are resilient and do fight back.

When we were talking about heroes earlier, of course I missed the obvious reply, which is the people on the front line who do fight back – for example, the miners and their families during the strike [of 1984-5], they’re obviously great heroic figures. And that’s true of all those big disputes.

There were some auxiliary hospital workers in Hillingdon, Asian women who had been wrongfully dismissed, and they sat on the picket lines outside for three or four years: no media attention, absolutely motivated – heroic figures. In Nicaragua, we met folk who had had their homes destroyed and family members killed by the Contra terrorists, who were paid for by the US to do just that, and yet they still fought on for a socialist Nicaragua. Again, heroic figures who made you feel very humble, almost like spoilt Westerners, in their company.

And, again, the people in Spain who fought for the POUM [the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification] against the Fascists, whose lives were wrecked as a result but who sustained their principles…

You seem to have a great faith in human nature.

‘Faith’ is the wrong word for me. I’m resisting that word… You can see that people do have an innate sense of justice and fairness and they do fight back. That’s really important.

Also, I think that what sustains you is a sense of politics. The only thing that makes sense of their oppression is the political system that demanded it. The US destroyed the Sandinistas, just as they destroyed Allende in Chile, because American capital demanded to maintain its influence throughout the continent – not because they were cowboys on the loose but because they were consciously seeking to defend their interests. So, I think if there’s a political framework to your understanding you can place what people are doing.

If history shows us one thing, it is that empires collapse – and when you least expect it

It’s only if you don’t have that perspective that you have illusions and therefore are disappointed. A political framework means you can place actions within it and see the logic – because there is a logic there. There was a logic to the US going into Vietnam and Nicaragua. It was vicious, monstrous, inhuman, cruel – you might say ‘evil’. But there was a logic to why they did it: to defend their interests. It’s seeing that logic that sustains you, I suppose.

And that political framework must be strong enough to take your faith – and hope? – in it. Can you give a name to it? Democratic socialism?

Well – if it isn’t a kind of albatross to hang around your neck – Marxism is the fundamental analysis of how societies develop, how class interests develop, how they express themselves, how they conflict – and also how capital has worked, how it developed from feudalism and so on. It’s been endlessly refined, but that’s the template you can put on society and everything fits. It does fit.

You’re not put off by the failure of Marxism in many parts of the world?

Which parts are you thinking of?

The embracing of capitalism in China, say?

Yes, but then it ceases to be Marxist, doesn’t it? Like Stalinism, which destroyed the Russian Revolution in its infancy.

So, Marxism has not been tried and found wanting, it has been found difficult and left untried?

Yes – or where it has been tried, maybe tentatively, maybe not 100-per-cent correctly, but people have genuinely tried to make an egalitarian society, to take control of their own destiny and of their own production and so on – in Chile, for example, and Nicaragua – the US just destroys it.

What hope do you have that that immense capitalist power can be overcome?

The thing is, history is dynamic. Nothing lasts forever. If you were an Ancient Brit you would have thought, ‘Christ, the Romans are here for eternity!’ – but of course their empire collapsed. If history shows us one thing, it is that empires do collapse. And it happens when you least expect it. I mean, no one would have expected Stalinist Russia to collapse overnight, but suddenly it’s a pack of cards.

Who knows? Globalisation makes for a very unstable world, because investment is switched from country to country, creating a boom here, mass unemployment there, creating whole areas of deprivation and rage and discontent.

Certainly the attack on the World Trade Center made everyone feel suddenly vulnerable. How did that fit in your framework?

It was horrific – probably less horrific than many of the examples of torture and terrorism that you could list throughout the world, but horrific nonetheless. But, I guess, given what the US has done around the world, the people they have bullied and butchered and invaded and terrorised, the surprise is not that it happened but that it didn’t happen before.

A slightly longer version of this interview was published in the September 2002 issue of Third Way.

To make sure you hear of future interviews in this series, follow High Profiles on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

| ⇑1 | Notably, Miguel d’Escoto served for many years as foreign minister, Fernando Cardenal as minister of education and Ernesto Cardenal as minister of culture. |

|---|

To find out more about the agenda behind our interviews, read our manifesto. To access our archive of more than 260 interviews, see the full list.

Biography

Ken Loach was born in 1936 and educated at King Edward VI Grammar School. He studied law at St Peter’s Hall (now College), Oxford (of which he was elected an honorary fellow in 1993). He joined the university’s Experimental Theatre Club and, after graduation, spent two years in the theatre.

In 1963, he joined the BBC drama department as a trainee director. His early broadcast work included the serial The Diary of a Young Man (1964), followed by some episodes of Z Cars and a succession of Wednesday Plays including Three Clear Sundays, The End of Arthur’s Marriage, Up the Junction and The Coming Out Party (all 1965), Cathy Come Home (1966) and In Two Minds (1967).

Subsequent work for television included The Golden Vision (1968), The Big Flame (1969), In Black and White (1970), After a Lifetime (1971), The Rank and File (1972), the mini-series Days of Hope (1975), The Price of Coal (1977), Auditions (1978), The Gamekeeper (1979), A Question of Leadership (1980), Questions of Leadership (1983/4), whose broadcast was banned, Which Side Are You On? (1984), The Flickering Flame (1996) and Another City (1998).

His first feature film, Poor Cow, was released in 1968. This was followed by Kes (1970), which won the Karlovy Vary Award, Family Life (1972), Black Jack (1979), Looks and Smiles (1981), which won the Contemporary Cinema Prize at that year’s Cannes Film Festival, Fatherland (1986), Hidden Agenda (1990), which won the Jury Prize at Cannes, Riff-Raff (1991), which won the Felix for the best European film of the year and the International Critics’ Prize at Cannes, Raining Stones (1993), which won the Jury Prize at Cannes, Ladybird Ladybird (1994), Land and Freedom (1995), which won the Felix for best European film of the year and the International Critics’ Prize and the Ecumenical Jury Prize at Cannes, Carla’s Song (1996), My Name is Joe (1998), which won the award for best actor at Cannes, Bread and Roses (2000), The Navigators (2001) and Sweet Sixteen (2002), which won the award for best screenplay at Cannes.

He was offered an OBE in the late Seventies but turned it down.

He has been married since 1962, and has two surviving sons and two daughters.

Up-to-date as at 1 August 2002