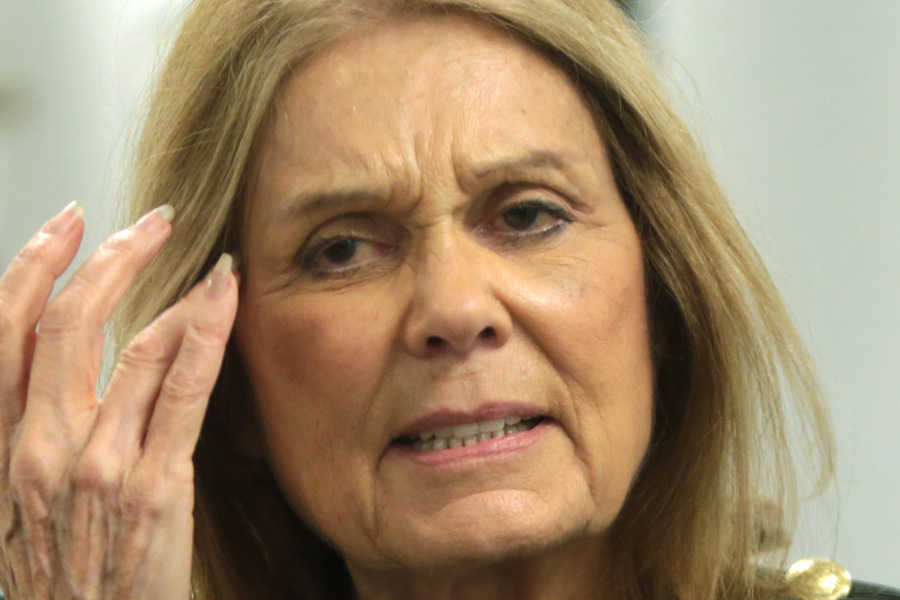

Gloria Steinem

has been for decades (as she put it) a ‘somewhat accidental’ symbol of the women’s movement. On 21 January 2016 Elaine Storkey rang her at her home in New York.

Photography: Gage Skidmore

I’m looking at a lovely picture of you by Annie Leibovitz in Vogue,1See vogue.com. which shows you sitting pensively at your desk, exuding peaceful solitude…

It must have been a rare moment!

In your latest book, My Life on the Road,2Oneworld Publications, 2015 you describe a struggle in yourself between individualism (inherited both from your father and, I suppose, from US culture) and community. I’m curious to know when that conflict was resolved for you, and how.

I understand what you mean, but the tension in my life was more being on the road versus making a home. I think it was always fairly clear to me that I needed a community wherever I was, and the social justice movement certainly provides a community; but it doesn’t necessarily provide a home.

I had not had a home when I was growing up – or, at least, not a very consistent home, since we were living in a trailer much of the time and I wasn’t going to school. I found myself longing for the life I saw in the movies, in that way that as children we want to be like everybody else. I kept thinking that I wanted a normal house and to go to school like the other kids, and to have a horse, you know?

I found your account of your upbringing quite moving – your father’s restlessness and optimism, your mother’s struggle, mentally and emotionally, with the kind of lifestyle you had. What questions would you ask them now about the way they brought you up?

Well, the most important thing about my parents was that they loved me and they treated me better than they treated themselves. I recognise their struggle in their own lives, and that [affected] me; but I also feel lucky that I had that kind of parenting. You know, they treated me like an individual, no matter how young I was, and asked me what I wanted – which many parents don’t.

I love the story that you pointed out to your father that you couldn’t have dessert because you hadn’t finished your first course, and he said: ‘But sometimes you’re hungry for one thing and not another.’

That was so, so like my father!

You identify the National Women’s Conference in Houston in 19773The Conference was held over four days and attracted some 2,000 delegates and 15–20,000 observers. The goal was to agree a ‘plan of action’ on women’s rights to be presented to President Carter and Congress. as one of those events that divide life into ‘before’ and ‘after’. Why do you see it that way? You were already a very strong feminist then, weren’t you, and already changing people’s lives?

The most important thing about my parents was that they loved me and they treated me better than they treated themselves

Well, I see what you mean. I could also divide my life into before and after going to cover an abortion hearing [for New York in 1969] and hearing women tell the truth in public for the first time. That was also a dividing line. It’s just that – how shall I say? – that hearing made me understand what was wrong, that we had a right to stand up and speak about unequal treatment; but I’m not sure that before Houston I understood that women could do everything in the world that men do. In my heart I think [that] because I had never before seen women running massive national events, I had internalised certain unconscious ideas of what women were and were not capable of. And suddenly I realised that of course we can do anything that men can do, and vice versa – we’re all human beings.

For instance, we were worried about security because there were massive right-wing protests against that conference and so, with money we could ill afford, we hired a group of retired police officers who had previously provided security for the Democratic Convention. As it turned out, there were hundreds of women in red T-shirts who were accustomed to doing movement events and they were the ones who provided the real security. The cops hadn’t a clue what was going on.

I laughed my socks off when I came to that bit!

So, you might say that what I learnt from the abortion hearing was more remedial, but this was more positive.

You talk about the three stages of your political involvement: your volunteering as a student, and then the founding of the National Women’s Political Caucus4See www.nwpc.org/about. in 1971, and finally the independent campaigning, undertaking real democratic enquiry that got to the heart of what representative government is all about. Why do you think that campaigning was so successful?

Social justice movements are trusted more than political parties, so it seems important to contribute what we can uniquely contribute, as opposed to just volunteering inside a political party and repeating what’s already been done and saying the words that are already being said. There’s a general principle that you and I are probably doing the right thing when we do what we can uniquely do, and I think that’s true of groups as well.

How easy do you find it to deal with misrepresentation by the media?

It’s very frustrating, because there seems to be a generalised media [assumption] that only the negative is news, which is, I think, part of the reason that, in [the US] at least, many people don’t feel positively about the media. As our networks say, ‘If it bleeds, it leads.’ And that [applies to] the movement – or any social justice movement – so that only conflicts within it are news. It’s important to know the negative news, but it’s also important to have news of solutions – that is crucial.

What about when you are misrepresented yourself?

Well, for a long time it was very difficult. I felt as if I was standing on the ground and I was holding the string of a large balloon which was floating in the air, which the media were treating as if it were me. It just felt out of control. Over time, it has gotten better, just because, you know, the impressions [given] of a single human being can’t remain completely inauthentic over a long period of time. So, now that it’s, like, 40 years later – or almost 50 years – it’s not as bad as it was; but it is still annoying. I mean, I’m 81 years old and I’m still introduced sometimes as an ex-Bunny!5In 1963, Steinem worked undercover for a month at the Playboy Club in New York, to write a two-part exposé for the magazine Show. See bit.ly/1LgGhBu.

I have a great kinship with people inside monotheistic institutional religions who are striving to restore spirituality to those religions; but I do feel that monotheism is part of the problem, not the solution

Your attitude to organised religion is often very negative – which is completely understandable – but you describe yourself as a pagan who sees God in all things and you also identify with religious people who you feel express a similar sense of God, such as Father [Harvey] Egan.6A Roman Catholic parish priest in Minneapolis who controversially invited Steinem to speak from his pulpit in 1978

He was a wonderful man, yeah.

But there are many other people you clearly admire – Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Mahalia Jackson – who were involved in institutional Christianity.

You know, I have a great respect [for] and kinship with people inside monotheistic institutional religions who are striving to restore spirituality to those religions; but I do feel, myself, that monotheism is part of the problem, not the solution.

In what way part of the problem?

Because… ‘If God is male, then the male is God,’7Mary Daly in Beyond God the Father: Toward a philosophy of women’s liberation (Beacon Press, 1973) you know. Even India has different manifestations of godliness, so that there are female and animal personas and it [leans] a little more towards God in all living things.

Have you ever gone on a trip down the Nile? When you go, in a kind of houseboat, from the African [reaches] of the Nile towards Cairo, you go ashore and see the remains of old temples and so on, and in the oldest ones you can see that everything is represented: men, women, birds… When you [next] go ashore, it’s a thousand years later and suddenly there’s not so much nature and the goddess has a son but no daughter. Then you get back in the boat and it’s another thousand years almost and the son has grown up to be a [divine] consort. And this continues until you get to the mosques, which (like churches in Europe) are often built on top of pagan sites, and in mosques no representation of females or nature is allowed.

I was reading the [early-20th-century] Egyptologist James Henry Breasted and he said, you know, monotheism is but imperialism in religion. Withdrawing God from females and nature was part of making it possible to conquer females and nature.

I can see that completely. I think that’s why Christian theology today is focusing more and more on escaping from a gendered God to a God that is beyond gender but also is directly in touch with and delighting in creation.

You know, I can’t find any comfort in monotheism, but I do understand that there are many people within it who are trying to restore a sense of godliness in all living things, and I think we have common cause.

What do you think are the central issues for women globally today?

The central issue is, of course, women’s bodies. You know, the one thing men don’t have are wombs and the impulse of male-dominant cultures has been to control reproduction and therefore to control the bodies of women. So, establishing our right just to control our own lives from the skin in, and to be physically safe, is the central issue – or the most basic issue, I would say.

And then, of course, comes the question of work. Women’s work is often not paid at all, because what we do is not considered work, you know? I mean, what is considered work is something men could do, whether or not they are doing it.

But physical safety, I would say, and the ability to protect our own bodies have to come first, because (for instance) violence against females, in all of its forms, whether it is sexualised violence in war zones or female genital mutilation or domestic violence –

Violence against females convinces us that one group of people has a right to dominate the other, which then normalises racism, and normalises violence

Honour killings.

– or son surpluses and daughter deficits in China and India… For the first time that we are aware of, there are now fewer females on earth than males.

I’ve just written a book that looks at the ubiquity of violence against women.8Scars across Humanity: Understanding and overcoming violence against women (SPCK, 2015) I kept encountering this phenomenon when I was president of Tearfund – in different forms, for different reasons, with different justifications. What do we do about it?

I guess the short answer is ‘everything’. We do our best to protect each other, to change laws and police practices to show that anti-female violence is taken seriously and is not just seen as inevitable or even attracted by the victim (as sexualised violence frequently is).

There is a book called Sex and World Peace,9Columbia University Press, 2012 by Valerie Hudson and other scholars, which points out that the single greatest determinant of whether a country is violent within itself, or will be willing to use military violence against another country, is not poverty, not access to natural resources, not religion or even degree of democracy, it’s violence against females.

It’s not that female life is any more important than male life, no, but that it’s what we see first and most intimately. [Violence against females] convinces us that one group of people has a right to dominate the other, which then normalises racism and [religious discrimination and so on], and normalises violence.

The more we can explain that, the more likely we are to have foreign-policy-makers who understand their stake in combating violence against women because it’s what normalises all other violence.

It gladdens my heart to hear that articulated so strongly!

My book was reviewed by a bloke who said: ‘I can’t understand why Elaine Storkey bangs on about violence against women. There’s far more violence against men in the world.’

Yeah, well… When was the last time he walked in the street and was fearful in the way that many women are fearful?

Exactly. Can I ask what you feel about militarism and the kind of wars we are fighting today?

Well, it just seems obvious that the only reason for violence is immediate self-defence. I can see no other justification.

Actually, the single most frightening thing to me is that the ability to destroy large swathes of humanity with the hydrogen bomb and other doomsday weapons will coincide with the religions that are still teaching that life after death is better than life. I mean, as long as we want to live we can talk to each other, but when people believe that suicide will land them in heaven with all kinds of benefits, it’s very dangerous.

Who could argue with that? But are you saying that a religion that focuses on our human flourishing here and now is in itself better than a religion that claims that if you do the right things now, you’ll go somewhere better when you die?

Yes. And actually these very elaborate ideas of heaven came with patriarchy. The oldest cultures didn’t have elaborate ideas of heaven, they just said: When you die, you join your ancestors, or something. The idea that you might have a reward in heaven came with patriarchy, because the power of giving birth is, obviously, a huge symbolic power and essentially the patriarchal religions took it over by saying: Yes, you were born of woman, and therefore you were born in sin, but you can be reborn through men, and we will sprinkle imitation birth fluid over your head and give you a new name and – if you obey the patriarchy – we can go one better than women and give you everlasting life.

We are each of us unique and each of us part of a shared human family that is a circle, not a hierarchy. We are linked, not ranked

How would you conceive of heaven if you believed in such a thing?

I don’t believe in heaven. I mean, I think we all – all living things – change form. As physicists are always telling us, nothing is destroyed, it just changes form.

So, what will become of your human identity? Or is there no such thing?

You know, I don’t know. I was the child of a mother and two grandmothers who were theosophists, so they believed in reincarnation. I don’t think I do. There is a cycle of life, but I am not so egocentric as to think that you’re just going to turn up as some other person. It doesn’t make sense to me.

Do you see justice as something transcendent or is it just a matter of doing as you would be done by?

Well, certainly [you should] treat other people as you would want to be treated. I mean, the Golden Rule is quite practical. However, I do think that women have to reverse it sometimes, because we need to learn to treat ourselves better – as well as we treat others.

Yes, absolutely.

But in any case there is some sort of balance there – a sense that you and I are not more important than anyone else but we’re not less important, either, and that any hierarchy that is based on sex or race or ethnicity is unjust. It’s just plain wrong. Each of us is a unique miracle of heredity and environment combined in a way that could never have happened before and could never happen again.

That’s one truth. The other truth is that we are human, we share humanity, so we are each of us unique and each of us part of a shared human family that is a circle, not a hierarchy. We are linked, not ranked.

It’s interesting that I am within the Christian framework and you are somewhere outside it and yet we agree fundamentally about the unique significance of every human person and the wrongness of hierarchy, which nearly always leads to injustice and the abuse of power.

You know, I suspect that the paths that you and I have chosen, different paths to the same goal, probably has to do with the way we were brought up.

Oh, it probably has a lot to do with that!

Right! And both paths are fine. We couldn’t possibly be all on the same path, right?

Of course not. I suppose I’d want to say that for me there is something very significant about prayer: bringing my needs, as well as what I see as the needs of the world, to what I believe is a personal God. That certainly helps to articulate what is wrong and what needs to be done.

Right. Well, you know, prayer and meditation are the same thing, really. I mean, we’re… How shall I say? We’re putting a hope and an intention out there, which is crucial. Hope is in and of itself a form of planning.

I suppose the main difference between us is that my hope ultimately is in a Saviour. I can understand that you would see that as part of the patriarchy…

Well, I read Elaine Pagels’ book The Gnostic Gospels10The Gnostic Gospels (Vintage Books, 1979) and it did seem to me that Jesus was a far nicer guy than he is often portrayed.

What gives me faith that we can have a culture once again in which there is no hierarchy based on birth is that it did exist for most of human history

Yes, I think so.

I mean, he presented himself as a teacher. According to The Gnostic Gospels, he didn’t say he was the Son of God and he made fun of the idea of heaven – sort of ‘If heaven were in the air, the birds would be there. If heaven were in the ocean, the fish would be…’ You know? In the gnostic scrolls, he seems like an utterly admirable person.

Even in the traditional Gospels, he shows enormous respect for a menstruating woman and he tells her that it’s actually her faith, her initiative, her sense of rightness that have freed her. I think there’s lots of positive things going on there.

Yeah, and there’s a lot of rewriting going on there, but there still remains that verse ‘If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you.’11From the Gospel of Thomas You know, that is still so present.

Is there anything you would have done differently, looking back…?

Oh, I’m sure. Hundreds of things! Hundreds of things!

The thing that comes to mind is that I wasted time – and since time is all there is, really… I mean, I wasted time by continuing to do things I already knew how to do, rather than pressing the boundaries.

For me, this has a lot to do with writing, because the irony of a social justice movement is that it gives you what you want most in life to write about but it takes away the time to do it. I do wish I had written more.

What would you have written?

Well, you can only write things at certain times in your life, so if I’d been writing in Toledo [where I grew up,] I probably would have written a novel called ‘Getting Out’!

Would it have had a heroine?

Well, I’m no heroine, but it would have had a personal voice, yes. Actually, I can’t imagine myself writing fiction, because I’m just too interested in what’s actually going on.

There’s something I should have written long ago when Wilma Mankiller was still alive, who was the chief of the Cherokee Nation – and I’m still going to try to do this, to write about features of indigenous cultures that we could learn from and restore now, because there is a past, in pretty much every part of the world that I know about, of circular rather than hierarchical structures. There were indigenous cultures which did not have the same kind of gender roles – indeed, their languages didn’t even have ‘he’ and ‘she’.

You know, the degree of violence in society is related to the whole idea that hierarchy is the only form of social organisation. What gives me faith that we can have a culture once again in which there is not the same kind of hierarchy based on birth is that it did exist for most of human history, so it could exist again in a new way. I’d like to draw attention to those cultures.

This edit was originally published in the March 2016 issue of Third Way.

To make sure you hear of future interviews in this series, follow High Profiles on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

| ⇑1 | See vogue.com. |

|---|---|

| ⇑2 | Oneworld Publications, 2015 |

| ⇑3 | The Conference was held over four days and attracted some 2,000 delegates and 15–20,000 observers. The goal was to agree a ‘plan of action’ on women’s rights to be presented to President Carter and Congress. |

| ⇑4 | See www.nwpc.org/about. |

| ⇑5 | In 1963, Steinem worked undercover for a month at the Playboy Club in New York, to write a two-part exposé for the magazine Show. See bit.ly/1LgGhBu. |

| ⇑6 | A Roman Catholic parish priest in Minneapolis who controversially invited Steinem to speak from his pulpit in 1978 |

| ⇑7 | Mary Daly in Beyond God the Father: Toward a philosophy of women’s liberation (Beacon Press, 1973) |

| ⇑8 | Scars across Humanity: Understanding and overcoming violence against women (SPCK, 2015) |

| ⇑9 | Columbia University Press, 2012 |

| ⇑10 | The Gnostic Gospels (Vintage Books, 1979) |

| ⇑11 | From the Gospel of Thomas |

To find out more about the agenda behind our interviews, read our manifesto. To access our archive of more than 260 interviews, see the full list.

Biography

Gloria Steinem was born in Toledo, Ohio in 1934 and was educated at Waite High School in Toledo and Western High School in Washington. She attended Smith College, a private women’s liberal arts college in Massachusetts, graduating in 1956.

After two years in India as a Chester Bowles Asian Fellow, she was hired in 1960 as assistant editor of the satirical magazine Help!. Esquire gave her her first ‘serious’ freelance assignment, on contraception, in 1962. In ’63 she wrote ‘A Bunny’s Tale’ for Show and in ’64 she interviewed John Lennon for Cosmopolitan. In ’65, she wrote a regular segment for NBC’s weekly satirical revue That Was the Week that Was.

In 1968, she helped to found the magazine New York, for which she wrote a political column. In ’69, her article ‘After Black Power, Women’s Liberation’ brought her to national attention. In 1970, Time ran her essay ‘What It Would Be Like If Women Win’.

In 1971, she was one of more than 300 women who founded the National Women’s Political Caucus. She also co-founded the Women’s Action Alliance with Dorothy Pitman Hughes.

The following year, again with Pitman Hughes, she co-founded the liberal feminist magazine Ms., of which she was an editor for 15 years.

In 1992, she co-founded Choice USA (now Urge).

In 1993, she co-produced and narrated an Emmy-Award-winning documentary for HBO called Multiple Personalities: The search for deadly memories and co-produced for Lifetime a TV movie, Better Off Dead.

In 2005, she co-founded the Women’s Media Center with Jane Fonda and Robin Morgan.

Her books include Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions (1983), Revolution from Within: A book of self-esteem (1992), Moving beyond Words (1993) and, in India, As If Women Matter (2014). My Life on the Road was published in 2015.

She has received numerous honours, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Eleanor Roosevelt Val-Kill Medal in 2013.

She was married from 2000 until her husband’s death in 2003.

Up-to-date as at 1 February 2016