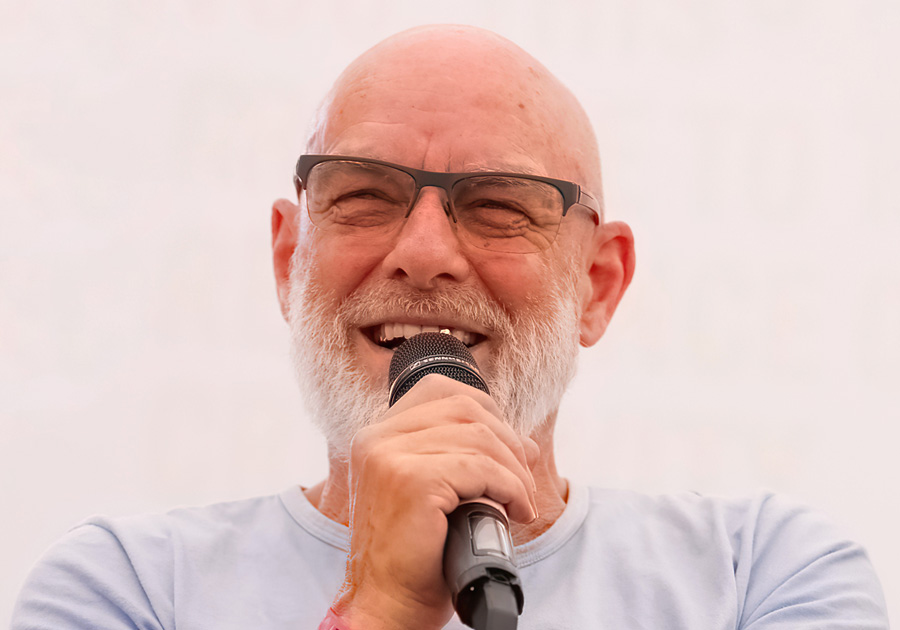

Brian Eno

has been hugely influential since the Seventies as a constant innovator in both popular music and visual art.

On 27 August 2022 – 50 years and a week after the release of his first single with Roxy Music – he conversed with Martin Wroe on stage at the Greenbelt Festival.

Photography: Philip King/Greenbelt Festival Photography

Was there ever a time when you were not an atheist?

I grew up a Catholic. I went to a Catholic school and had a normal Catholic education (which of course included the statutory molestation by a couple of Brothers), until I was 15 or so, when I found that I was attracted to things that were not permitted by my faith. I became a sort of pragmatic atheist then so that I could have dates with girls.

Was there a Damascus Road moment when a great light went out?

Yes. She was called Lucy.

No, it was a little more intellectual than that. At a certain point, I was asked by one of the Brothers whether I ‘had a vocation’, and I don’t know why but I said: Possibly. I then received a lot of extra attention, which I didn’t really want, and I started to think about this subject quite a lot more.

I always used to win the religious knowledge prize (and the art prize – a funny combination, really) and for one project we were asked to choose a book of the Bible to write about, and I chose the Song of Solomon, which I just regarded as a beautiful erotic poem.

I discovered that in the Egyptian Book of the Dead there was a very similar [poem] – and I thought: Oh, they just copied it from the Egyptians! They sampled it, really. And then I started to wonder about how fluid religions were.

That was the beginning of the step away from religion, I think. And then, of course, I read [Richard] Dawkins,1Interviewed for High Profile in February 1995 who has a very good [line]: There are about 3,000 gods in the world and the only difference between me and a believer is that I don’t believe in any of them, whereas they believe in one of them.2eg ‘We are all atheists about most of the gods that humanity has ever believed in. Some of us just go one god further’ – A Devil’s Chaplain: Reflections on hope, lies, science, and love (Mariner Books, 2004)

I started to realise that religion was something you made up, in the same way that you made up art. (This is a recent verbal formulation of it. For a long time, I’ve been getting to the point of thinking that art is necessarily fictional – that’s the whole point of it: to be another world from the one we’re in, to not be reality.) And I started to wonder if religion is a form of art, but a form that isn’t yet aware of being art, because it insists on its own truth, whereas forms of art don’t – they are necessarily malleable.

Who or what is the God you particularly don’t believe in?

When I look at the world, I don’t see something made by an intelligent being from the top down. I see a world that is kind of stumbling into existence and is always in the process of emerging, of making itself

Ever since I started thinking about this issue, I thought: Why do [people want a deity]? What does it explain? I mean, I understand that having a unifying body of doctrine is a way of holding people together; but [we are] advanced beings, on a planet that probably has more intelligence on it than it has ever had before (even if you just think in terms of brainpower, let alone what is done to amplify that brainpower). Isn’t it possible for us to learn to come together and be civilised with each other without having the threat of hell, for example?

I seem to be able to do that, inasmuch as I do, without having a God in my life. I don’t really understand what God exists for.

You’ve said that you like the notion that maybe all life is a simulation. A recent newspaper article put it like this: ‘We are just immaterial software constructs running on a gigantic alien computer simulation.’3theguardian.com/books/

So, this really came from a friend of mine, Kevin Kelly, who used to be the editor of Wired. Kevin calls himself an evangelical Christian – in fact, I’ve been to church with him a couple of times – and yet he’s probably one of the most tech-savvy techno-utopians I’ve ever met. He’s very interested in big computer games like Warcraft and Minecraft that involve hundreds of thousands of people making something together, and he said to me a few years ago: ‘Imagine if our world is actually a game that somebody else has made. Wouldn’t you call the person who made that game “God”?’

I said: ‘Yeah, well, I guess you could use that term loosely to describe the person who designed the whole thing.’ And he said, ‘Well, that’s what I believe might be the case. And actually I think that person who did the designing might simply be another piece of software in somebody even further away’s simulation, you know?’

When someone asked Kelly to reconcile such an idea with being Christian, he said that his epiphany came from looking at ‘God games’ and he put it like this: ‘Those who create the rules always want to put themselves inside the world they have made to see how it feels.’ And there it was, he said: the Christian story. The Incarnation.

Yeah, well, Kevin’s very good on this. We argue about it quite a lot.

I still don’t know why it’s necessary to posit that things came into being that way. I mean, for me the great revelation of Darwin was that complexity arises out of simplicity. Prior to Darwin, everybody assumed that the complexity that we see around us, in each other and in nature, must have been created by an even more complex being, God.

What Darwin showed is that it doesn’t have to work that way round. In fact, it doesn’t seem to work that way round: the complexity that we see around us arises out of simplicity, simple chemical processes and evolutionary processes.

And that seems to me so much more elegant, and so much more true to what I see. When I look at the world, I don’t see something made by an intelligent being from the top down, I see a world that is kind of stumbling into existence with all of the complexities and difficulties of that, and is always in the process of emerging, of making itself.

In the Jesuit tradition, there’s a concept of what is known as ‘consolation’, when through your faith you feel close to the Divine, and ‘desolation’, when you feel distant from the Divine. What is the consolation of atheism for you, and what is the desolation?

I’m afraid there isn’t much consolation in atheism, and I think that is why it’s hard to sell. I was talking to a friend the other day who had just been to the funeral of an atheist and he said: ‘It was kind of empty in a way, because we were just saying goodbye to this guy but none of us could say, “We’ll see you in eternity.”’ And that’s a hard thing to…

The only [positive] thing, I think, is that that can make you think: If I’m going to do something, I’d better do it now. There’s not going to be another chance.

We’re oppressed by corporations and by all the people using the system to make vast fortunes while a large part of the population gets poorer and poorer. We’re stuck in a system we want to change

It also gets over the slightly cowardly thing you find in Catholicism of ‘Well, you’ll get a chance to sort it out later with God.’ To me, that’s a little bit like carbon-offsetting. I don’t really believe in carbon-offsetting, either, because basically you really don’t want to do the damage in the first place, rather than do the damage and then kind of try to make up for it.

How would you describe the atheism you’ve ended up with?

For a while, I was very evangelical about it. What really changed, I think, was [that] when I moved to New York [in 1978], I started to listen to a lot of gospel music, just as music. I really, really loved it – I was very surprised that none of my cool arty friends ever listened to it.

And I started to think: This is very strange. How can I love this music that is celebrating this entity that I don’t believe in? I wrestled with this for a long time. But after a while I thought: Does it really matter? I like 16th-century religious paintings, but it doesn’t trouble me that I don’t believe that Mary was really a virgin, for example. Those questions don’t even enter my head.

If I listened to only one gospel song, what should it be?

I think right now it would be a song by the Rev James Cleveland called ‘Peace Be Still’.4youtube.com/watch?v=yfIjj-wN93Y You have to hear it loud the first time you hear it, so don’t go and play it on your bloody phone. It’s a really overwhelming experience, if you let it be.

You’re a man of the left. Are you troubled at all by the origins of gospel music in the spirituals of the slave plantations?

I think the central message of gospel music is: Everything’s going to be all right. There’s an optimism about it that I find very moving, because I’m not naturally an optimist. Actually, I’m quite pessimistic about the future.

But it’s [also] music that came out of the experience of oppression, and we are also oppressed now, by much vaguer entities than slave traders. We’re oppressed by corporations and by all the people using the capitalist system to make vast fortunes while a large part of the population gets poorer and poorer. Of course, we are a lot freer than many other humans are; but we’re still stuck in a system that we want to change.

So, I think we share those [sentiments] with the people who created gospel music.

I moved to San Francisco for a while and I used to go to a different gospel church every Sunday, just for the music. It was such a moving experience for me. There was something about the community aspect of it, really – because the kind of gospel music I liked was not the sort of smooth, Andrae Crouch stuff that was starting to appear then, it was a lot of people in church singing. I’d always thought that was the best thing about church anyway.

I started to think: I don’t believe in God, but I believe in religion. I like many of the things that religion does.

I saw this amazing film called Hoover Street Revival,5Directed by Sophie Fiennes in 2002 about a church in a very poor part of south central LA. The pastor of that church is actually the brother of [the singer] Grace Jones, and he is just as glamorous as Grace. He’s a very stylish guy.

He runs this huge church, which provides creches, soup kitchens, after-school lessons for kids who are in broken or difficult homes, places for people who are homeless to find some solace – everything that society ought to be offering these people. And I realised, watching that film and then meeting Noel Jones later, that this was fulfilling a very important social function, creating a community for people who didn’t really have much else. They didn’t have much money, any of them, but this community gave them such strength and such a feeling of belonging, and such power from that.

So, having walked away from formal religion, you began to walk back towards it when you experienced both the power of music expressed in religious communities and the engagement of religious communities in community life.

And noticing how religions existed for a different reason [from] most other organisations. They weren’t there to make money – at least, in theory – they weren’t there to be fun; they were there for something different – and I liked the thing that they were there for.

And noticing how religions existed for a different reason [from] most other organisations. They weren’t there to make money – at least, in theory – they weren’t there to be fun; they were there for something different – and I liked the thing that they were there for.

I started to feel more and more [that] this is a way of threading together people’s experiences, giving them a sense of being part of something bigger, and therefore not putting the onus on everyone all the time to be the centre of [their own] life.

The great problem with the capitalistic societies we live in now is that we are so atomised. Atomised humans are much easier to sell to. If it’s set up that you are in competition with your neighbour about what kind of curtains you have and what kind of car you have, you get this fractured society that doesn’t seem to [have] anything in common. Of course, that’s [countered] by a few things. Sport is one of those things, art is another and religion is another.

In 2000, you started your own choir. Was that partly to try to bring those two things together, the music and the community?

I didn’t realise it at the time but that’s what it turned out to be. I wasn’t writing songs any more at that time but I love singing and I wanted a way of singing regularly, so I started this little acapella group with a friend of mine. We would meet every Tuesday evening and the group started getting bigger and bigger, until in the end I had to reduce it a little. It’s stabilised at about a dozen people now.

This group of singers is extremely diverse – like, we’ve got a social worker from East London, we’ve got England’s leading tax barrister, we’ve got a boxer, a theatre designer, an insurance actuary – we have all sorts of people. And they’re people who probably would not meet in any other circumstances – except a church, actually.

I was going to say that.

And it sounds like a church when we’re singing! It’s the best feeling for me.

Your choir has never released any music. Is it simply for the joy of singing?

Yes, that was our first rule, really: no recording, no performing. It’s about participation, and it’s about being in the moment and loving the people you’re doing it with.

That’s the most interesting [aspect] to me. When people sing together, they have a different respect for each other and a different bond with each other. It goes beyond anything to do with politics or identity – you know, all those culture-war things that are now being used to divide us up into neat voting blocs. People find a kind of love for each other.

And I use that word carefully. I don’t throw that word around. There is a real love among people who sing together.

You’ve also discovered that religion gives people a chance to surrender, I believe.

This was a big thing for me: suddenly realising that a part of me just wanted to let go and be part of something. When I went to these churches in San Francisco, I used to join in, obviously, and that experience of singing with a group of people who are singing passionately is not like anything else that can happen to you.

Well, that’s not quite true. I think there are four main [areas] in our life where we really want to surrender and we allow ourselves to; and they are sex, drugs, art and religion. I think we’re drawn to all of those experiences because we are offered the chance to no longer be just ourselves [but] to be part of something bigger, something that isn’t under our control.

Technical civilisations like [ours] evolve around the ability to control things. Our civilisation is very proud of its ability to control nature, to discover things and build new things, to fly across oceans and so on and so on. And we – quite rightly, I suppose – celebrate those among us who are good at controlling.

What we don’t celebrate, and I think we ought to, is the people who are good at surrendering as well. Surrendering isn’t a passive thing, in my opinion: it’s a decision to become part of something, part of something that you don’t control. One of the things that people always so admire about animals, and people they call ‘primitive’, is that they’re actually very good at surrendering. They know when to hold their ground and they know when to go with the flow. We are not so good at the latter. We always think, ‘This is a problem. How do I fix it?’ rather than ‘This is a problem. How do I not let it affect me, go with it, float in it?’ sort of thing.

The thing that humans treasure more than anything else is the feeling of belonging to something – even if it’s Make America Great Again. It’s something that the left has consistently failed to grasp

I think that we need constant rehearsal in surrender – and I think that’s why we like all of those things I mentioned. They’re all opportunities to stop being a single, atomised ego and become part of a flow of something. And we like that. I think the thing that humans treasure more than anything else is the feeling of belonging to something – even if it’s, you know, Make America Great Again. A lot of the power of [such phenomena] is that they give people a home, a place where they have connections and they have respect.

That seems to me very important. It’s something that, I’m afraid to say, the left has consistently failed to grasp for the last 40 or 50 years.

So, what people want from religion and what they want from art is the same thing: surrender?

Yes. I don’t think that is the only thing you want from them, but I think it’s [something they have in] common, and that is what led me to think that maybe religion is a form of art.

You’ve worked on so many influential albums, and recorded many yourself, but the one I want to talk to you about is your 2008 collaboration with David Byrne, Everything that Happens Will Happen Today.6Released by Todo Mundo You’ve described it as ‘an electronic gospel album for atheists’.

Another great sales line!

It is what some might call ‘transcendent’ music.

We had made a record together, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts,7Released by EG Records in 1981 which was very influential. We stayed in touch as friends for many, many years and we had dinner one evening and I said: ‘I’ve been thinking a lot about the kinds of feelings you can get from gospel music, music that invites [you] to sing along with it – that’s the point of it. What about making something that uses all the skills we have in making records in recording studios but tries to say: ‘Sing along, join in! This is not about us so much, this is for you’?

Of course, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts also was a way of saying ‘This is not about us’ by sampling other people’s voices from radio stations and other records.

In pop music, everything is assumed to be autobiographical, [but] there is no less interesting subject to me than me. I don’t want to make autobiographical music. You know, Bowie was well aware of this possibility of creating a scenario – writing a little play, in a way – and that appeals to me much more: just presenting a little world that doesn’t have to have you in it, sort of thing.

And David [Byrne] had reached exactly the same point in his thinking. And I had a lot of music then that didn’t have lyrics and he had a lot of lyrics that didn’t have music, so we thought: This should work!

Well, it worked for me.

It didn’t work for many people. It wasn’t a great-selling record.

It’s not all about sales, Brian.

No, no, quite right. Thank you for reminding me. You should be a record producer.

What was it like to work with David Bowie?

I always find biographical questions embarrassing and slightly irrelevant, but I will tell you that it was mostly very funny being in the studio with him. He was one of the funniest people I’ve ever met, and was a very good mimic (a lot of good singers are). Most of the time that I can remember with David, where we were making these quite serious records like Low and ‘Heroes’,8In 1976–7 we were talking to each other as Pete and Dud.9See eg youtube.com/watch?v=hvQq_tqB0jA. It’s difficult for people to [imagine] that you can be doing something that is intense and passionate and involved and also be funny.

The paradox is that we’ve reached the peak of human power without at the same time reaching any kind of peak of human responsibility. Of course, that’s what the climate crisis is about

In fact, I don’t trust people any more who aren’t funny.

You are one of the people behind the Long Now Foundation.10longnow.org Can you say a little about it?

It was founded in ’96, by Kevin Kelly, Danny Hillis,11US inventor and entrepreneur Stewart Brand12US writer, best known as editor of the Whole Earth Catalog and some others – everyone apart from me was a sort of Silicon Valley type. It really came from Danny, who had just built the fastest computer ever made. [He noticed] that our ability to divide time up into smaller and smaller segments was increasing apace – at that time, they were talking about ‘femtoseconds’13A femtosecond is a million-billionth of a second. (I don’t know what they’re up to now – zeptoseconds14A zeptosecond is a billion-trillionth of a second. It takes a photon 247 zeptoseconds to traverse a molecule of hydrogen. or something) – but at the same time we were becoming less and less conscious of the long term. The paradox was that we’d reached the peak of human power without actually at the same time reaching any kind of peak of human responsibility.

Of course, that’s what the climate crisis is about: that we’ve had the power to change the world without ever thinking through the implications of doing that.

So, we were trying to think of ways of encouraging people to think in the much longer term. Danny had designed a mechanical clock [that would] run for 10,000 years. It sounds like a stupid idea, but it’s actually very interesting as soon as you start engaging with it. If you tell people about the clock, they say: ‘Well, what if there’s a, you know, collapse of civilisation?’ OK, let’s think about that! How would you have to make this thing for it to survive a collapse of civilisation?

So, it starts the conversation, basically. As soon as people start thinking about the notion of 10,000 years into the future, they start to think beyond the year 2030 or whatever our current vision of the future is.

We wanted to make experiencing the Long Now Clock a secular sort of pilgrimage (we use the word ‘pilgrimage’ quite a lot). It is nearly built: it’s 580 feet high and it’s in a mountain in Texas and it’ll be finished next year, but it’s a long way from anywhere and you’ll have to work to get there – you have to get 6,000 feet up the mountain.

And the hands on the clock will turn a complete circuit every 10,000 years?

Yes.

We wanted the clock to have a chime of bells, as clocks do, and I got my calculator out and I realised that if you had 10 bells you could have a different chime for every day of 10,000 years. There’s almost exactly the same number of days in 10,000 years as there are permutations of 10 bells. I think it’s 3,680,000 and something.

I was just working that out in my head.

Because it’s algorithmic, we can predict exactly what it’ll be playing on each day and [in 2003] I released an album, one of my less well-known records, called January 07003,15January 07003: Bell studies for the Clock of the Long Now (Opal Records) which was the peals of those bells 5,000 years in the future.

The title of your latest album, ForeverAndEverNoMore,16Released by Opal Records on 14 October 2022 also has a vaguely religious resonance…

The feeling of it is kind of melancholy because it’s nostalgic, some of it, for a future that didn’t happen. You know, I grew up in a time of prosperity after the war in – what do they call it? The ‘golden age of capitalism’. Which actually ought to be renamed ‘the golden age of socialism’, because that’s actually what it was, that was what made it. We got a national health service, we got social security, and we started doing things that helped ordinary people to live their lives.

So, I grew up in this assumption that everything’s going to be all right. And when that evaporated, with Thatcher and Reagan and monetarism and all of that sort of thing, we went back to something like the law of the jungle.

All the lines on the graph were going up until about 1979, when productivity carried on going up but workers’ wages flattened and then started to drop – and they’re still dropping now. So, the gap between the amount of wealth being generated and how much [the workers get] gets bigger and bigger.

People who are younger than me live in quite a different world and have different expectations about the future. Unfortunately, a lot of the people who would be my natural political allies still find themselves mentally in the world I grew up in. The record comes out of, I think, trying to abandon the expectations [of the world I grew up in] and to realise that we’re dealing with a harsher world now.

And to hope, also, that we might actually recognise that and do something about it.

Adapted from a live interview and audience Q&A at the 2022 Greenbelt Festival and used by kind permission.

To make sure you hear of future interviews in this series, follow High Profiles on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

| ⇑1 | Interviewed for High Profile in February 1995 |

|---|---|

| ⇑2 | eg ‘We are all atheists about most of the gods that humanity has ever believed in. Some of us just go one god further’ – A Devil’s Chaplain: Reflections on hope, lies, science, and love (Mariner Books, 2004) |

| ⇑3 | theguardian.com/books/ |

| ⇑4 | youtube.com/watch?v=yfIjj-wN93Y |

| ⇑5 | Directed by Sophie Fiennes in 2002 |

| ⇑6 | Released by Todo Mundo |

| ⇑7 | Released by EG Records in 1981 |

| ⇑8 | In 1976–7 |

| ⇑9 | See eg youtube.com/watch?v=hvQq_tqB0jA. |

| ⇑10 | longnow.org |

| ⇑11 | US inventor and entrepreneur |

| ⇑12 | US writer, best known as editor of the Whole Earth Catalog |

| ⇑13 | A femtosecond is a million-billionth of a second. |

| ⇑14 | A zeptosecond is a billion-trillionth of a second. It takes a photon 247 zeptoseconds to traverse a molecule of hydrogen. |

| ⇑15 | January 07003: Bell studies for the Clock of the Long Now (Opal Records) |

| ⇑16 | Released by Opal Records on 14 October 2022 |

To find out more about the agenda behind our interviews, read our manifesto. To access our archive of more than 260 interviews, see the full list.

Biography

Brian Eno was born in 1948 in the Suffolk village of Melton. He was educated at St Joseph’s College, Ipswich and gained four O-levels. In 1964, he enrolled at Ipswich School of Art, where he studied painting and experimental music. In 1966, he began a three-year diploma in fine arts at the Winchester School of Art.

Having played in a succession of bands, including Merchant Taylor’s Simultaneous Cabinet and the Maxwell Demon, he moved to London in 1969 and became involved with the experimental musical ensemble the Scratch Orchestra and the performance art ensemble the Portsmouth Sinfonia. For a while, he made a living buying old speakers and doing them up.

In 1971, he joined the glam/art rock band Roxy Music on mixing desk, synthesiser and backing vocals, co-producing their first two albums, Roxy Music (1972) and For Your Pleasure (1973).

He launched his solo career with the album Here Come the Warm Jets (1974), followed by Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) (also 1974), Another Green World and Discreet Music (both 1975), Before and After Science (1977) and Music for Films (1978). During this period, he played three dates with the supergroup 801, resulting in the album 801 Live (1976).

His subsequent solo albums include Thursday Afternoon (1985), Nerve Net and The Shutov Assembly (both 1992), Neroli (1993), The Drop (1997), Another Day on Earth (2005), Lux (2012), The Ship (2016) and Reflection (2017), which was nominated for a Grammy. ForeverAndEverNoMore was released on 14 October 2022.

His early excursions into what he named ‘ambient music’ were Music for Airports (1978), The Plateaux of Mirror (1980) with Harold Budd and On Land (1982). These were followed by Extracts from Music for White Cube and Lightness: Music for the Marble Palace (both 1997), I Dormienti and Kite Stories (both 1999), Music for Civic Recovery Centre (2000), Compact Forest Proposal (2001), January 07003: Bell Studies for the Clock of the Long Now (2003) and Making Space (2010).

He collaborated with many other musicians in the 1970s, most notably Robert Fripp (on (No Pussyfooting) [1973] and Evening Star [1975] as Fripp & Eno) and David Bowie, working on the latter’s albums Low and ‘Heroes’ (both 1977) and Lodger (1979). He was credited with ‘Enossifying’ Genesis’s 1974 album The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway.

In 1979, he created with David Byrne My Life in the Bush of Ghosts (1981). (They renewed their partnership in 2008 with Everything that Happens Will Happen Today.)

In 1983, he collaborated with his brother, Roger, and Daniel Lanois on the album Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks. In 1990, he worked with John Cale on Wrong Way Up. He was reunited with Bowie in 1995 on the latter’s album Outside and on the song ‘I’m Afraid of Americans’, which they co-wrote. He collaborated with J Peter Schwalm on Drawn from Life (2001) and with Paul Simon on the latter’s album Surprise (2006). With Fripp, he recorded two more albums, The Equatorial Stars (2004) and Beyond Even (1992–2006) (2007). He also recorded Small Craft on a Milk Sea (2010) with Jon Hopkins and Leo Abrahams; Drums Between the Bells (2011) with the poet Rick Holland; Someday World and High Life (both 2014) with Karl Hyde; and Mixing Colours (2020) with his brother.

He has twice won the Brit award for best British producer, in 1994 and ’96. The first album on which he was named as producer was Robert Calvert’s Lucky Leif and the Longships (1975). He has since produced albums by John Cale, Jon Hassell, Laraaji, Talking Heads, Ultravox, Devo and Zvuki Mu, as well as the ‘no wave’ compilation No New York (1978).

For U2, he co-produced with Lanois The Unforgettable Fire (1984), The Joshua Tree (1987), Achtung Baby (1991), All that You Can’t Leave Behind (2000) and No Line on the Horizon (2009); and with Flood and the Edge Zooropa (1993). In ’95, under the collective pseudonym Passengers, he and U2 created the album Original Soundtracks 1, which included the hit single ‘Miss Sarajevo’ featuring Luciano Pavarotti.

For James, he produced Laid (1993) and Wah Wah (1994) and co-produced Millionaires (1999) and Pleased to Meet You (2001). He was also credited for ‘frequent interference’ on their 1997 album Whiplash.

He co-produced Laurie Anderson’s Bright Red (1994) and worked with Grace Jones on her 2008 album Hurricane.

He produced Coldplay’s Viva la Vida or Death and All His Friends (2008) and contributed ‘enoxification’ to their 2011 album Mylo Xyloto.

He wrote the music for BBC2’s six-part fantasy series Neverwhere in 1996, scored Peter Jackson’s 2009 film of The Lovely Bones and provided original music for the 2021 documentary Ithaka.

In 1975, he launched the short-lived record label Obscure Records, which over four years released albums by Gavin Bryars, John Adams, Michael Nyman and John Cage.

Since his student days, he has also worked in other media. He has had scores of exhibitions of video artworks and audiovisual installations in museums and galleries worldwide, including the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (1984), the 1986 Venice Biennale, the Hayward Gallery (2000), San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (2001) and the 2005 Lyon Biennial.

His 2006 ‘generative’ art/music installation 77 Million Paintings has been shown all over the world and has been projected onto structures including the sails of Sydney Opera House, Carioca Aqueduct in Rio de Janeiro and the Lovell Telescope at Jodrell Bank.

Since 2016, his ‘light boxes’ have been seen all over the world.

His sound installations have been exhibited in the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York, Vancouver Art Gallery, the Pompidou Centre in Paris, the ICA in London and Baltic Art Centre in Gateshead, as well as at the Sydney and Venice Biennales and the São Paulo Art Biennial.

In 1975, he developed with the artist Peter Schmidt Oblique Strategies, a deck of cards designed to spur creative thinking. He is the author of the diary A Year with Swollen Appendices (1996).

He co-founded the Long Now Foundation in 1996. In 2013, he became a patron of the human-rights organisation Videre. He has been president of Stop the War Coalition since 2017, and is a trustee of ClientEarth, Somerset House and the Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose. He is a high-profile member of the Democracy in Europe Movement 2025, aka DiEM25.

He has an honorary doctorate from Plymouth University. In 2012, he was elected a Royal Designer for Industry by the Royal Society of Arts. In 2019, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of Roxy Music and was awarded a Stephen Hawking Medal for ‘science communication’ in music and arts.

He has been married twice and has three adult daughters.

Up-to-date as at 1 November 2022