Alan Garner

is an author whose novels are rooted in myth and legend. Philip Pullman has called him ‘the most important British writer of fantasy since Tolkien, and in many respects better than Tolkien, because deeper and more truthful’.

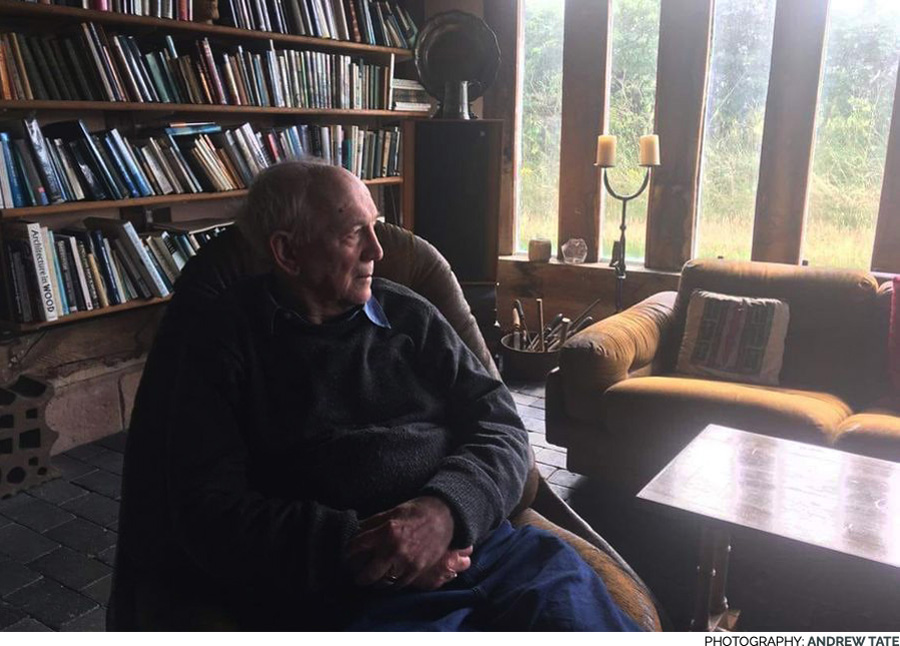

Andrew Tate sat at his hearth on 10 August 2021.

Photography: David Heke

We’re sitting in a beautiful, timber-framed building, on a site that has been settled since ancient times. It’s not a museum, it’s your house, but it is imbued with a sense of the deep past.

Oh, yes. People of all levels of education, all nationalities, who have come here have said: ‘This is a special place.’ A Japanese translator sat where we are sitting now and said: ‘This is the first time I’ve been home in months.’ I’ve had a Georgian poet sitting here in tears because of the smell of the oak.

It has certainly been a special place for you.

It has enabled me to write – that’s the least it’s done. But it would be hubristic beyond belief for me, having lived here for 64 years, to think at the end of my ninth decade that I could own 10,000 years. I just have to be grateful that I’ve had the opportunity to be a steward for a while.

Tell me about your childhood and the influences that made you the man you are.

I was an only child during a world war and lost more than half of my primary-school years through serious illnesses – meningitis, simultaneous whooping cough and measles, pneumonia and pleurisy. I was written off as dead three times. Did I become the man I am because I had to survive, or did I survive because those qualities were already there? I can’t answer.

On my father’s side, as far back as anybody can follow, my family were rooted geographically, manual craftsmen [who were] highly respected within a community that was deep in culture and narrow in vision. After a day cutting stone, which is highly skilled work, my great-great-grandfather Robert Garner would lie on Alderley Edge and (in his words, which have come down to me) compose music while ‘listening to the zephyrs in the trees: always in the minor key’.

On the maternal side, my family was a ragbag: gifted, eccentric charlatans, mentally and emotionally unstable, educated for their time but only at a primary level. Some of them never achieved a thing, but others were creative. One became bootmaker to Her Majesty the Queen!1Joseph Sparkes Hall, in 1837. He invented the elastic-sided boot and wrote ‘a history of boots and shoes’, The Book of the Feet.

It’s a strong mix. Not always easy to live with – certainly in adolescence.

You were the first member of your family to get a proper education. Did you seem exceptional in any way?

Realising that I could read was transformative and terrifying. To be able to move thought through space and time in this way is a wonder that has never left me

I was the clever one, the achiever, the ‘golden boy’ – and I went along with it. I’m not proud of that.

My mother felt that she had married beneath her, so I was actively discouraged from playing with my cousins on the paternal side, and I was paraded before my cousins on my maternal side as being superior to them. But for most of the time I was alone in bed in an 18th-century bedroom – which was the saving of me.

How did the storytelling begin?

My mother read nursery rhymes to me from the beginning, and my mother’s mother told me fairytales. I remember being in an isolation hospital and realising that I could read, too (I was looking at ‘Stonehenge Kit, the Ancient Brit’ in the Knockout, the best of all the comics). And then I took off. Through my grandmother I had access to an enormous number of books; and while recuperating from various illnesses I read them. I was memorising Shakespeare at the age of seven. I read the complete works of Charles Dickens.

My great-grandfather had been an autodidact and his library was full of the most astonishing stuff. Elements of the Fiscal Problem2By Leo George Chiozza Money, published in 1903 – I remember reading that. I didn’t know what ‘fiscal’ meant. I wasn’t reading with any maturity, I was just wallowing in the physical sensation of the words. I had from the very start a love of language.

You were precocious?

Yes, I was technically precocious, and emotionally precocious, too. I had a complete compost heap to ferment in, and I fermented.

Your latest novel, Treacle Walker,3Published by Fourth Estate on 28 October 2021 represents the experience of reading – in this case, a treasured comic – as both transformative and rather terrifying. Does that reflect your own experience?

The moment of realising that I could read was indeed transformative and terrifying – and remained so. To be able to move thought through space and time in this way, to be able to communicate with other, unknown minds, is a wonder that has never left me.

Are you musical? Your books certainly have a musicality to them.

I put that down to my education in Latin and Greek. Latin is a compressed language: it gets to the point. Greek is supple. It’s a language that can, linguistically, raise an eyebrow. I have no formal musical knowledge whatsoever, though music is an essential part of my life.

I would not have been a writer if I had not gone to Manchester Grammar School. That was the place that enabled me to become myself, and I owe it everything.

I came to English through acting, at school and later at university.4At Oxford in 1956, he was to play Mark Antony in Antony and Cleopatra. Ann Cook (who he married later that year) played Cleopatra and Dudley Moore played Enobarbus. At that time there was no English department at Manchester Grammar School. It was never expressed in this way, but English was treated as the language to specialise in if you couldn’t read in another language.

When did you start writing?

When I was 16, we read T S Eliot’s The Wasteland and I thought it was complete rubbish, and bad poetry because it had so many footnotes. To my horror, we were invited to go away and write something of our own. I thought: Well, I can write as badly as that. So, I wrote a parody of it, which was put in the school magazine.

I have not yet experienced religious faith, but that does not mean that I reject it. I see the cosmos as such a wondrous phenomenon that I can’t commit to what, to me, would be a narrowing down of it

There was a great English teacher called Heppell Mason, who spoke to me only once in my school career. I was walking along the corridor one day and he came up to me at a great rate of knots and grabbed hold of my sleeve, looked up at me – I was six feet two and he was about a foot shorter – and said: ‘Read your piece. Genuine Eliotian overtones.’

That would be early 1951. In 1968, I was in the school again, having just won the Carnegie Medal and the Guardian [Children’s Fiction Prize] for The Owl Service,5Published the previous year by Collins and in the corridor along came Heppell Mason. As he went past without stopping, he said: ‘What did I tell you?’

Have you warmed to Eliot since then? It strikes me you have a number of shared interests – for example, a fascination with time past and present and the way they blend and blur into each other.

That links back consciously to my bedridden childhood. I can remember having the ability – which I still have to a certain extent – of compressing or extending time subjectively.

I still don’t connect well with The Wasteland, but Four Quartets, ah, yes! And The Family Reunion, yes. Oh, boy!

Where did your sense of values as a young man come from?

I don’t know where my sense of values came from.

Was there any religion in your family?

No. My father was nominally Methodist. I was baptised into the Church of England and in due course, because they needed a server at communion, I was put through the Anglican puberty initiation rite – or confirmation – and gave the lovely, gentle vicar hell, because I approached his simple doctrinal instruction with the attitude and intellect of an aggressive academic classicist. He wasn’t expecting that.

Did you feel obliged to debunk something that struck you as nonsense?

Oh, not nonsense. I have not yet experienced religious faith, but that does not mean that I in any way reject it. I see the world, I see the cosmos, I see time as such a strange and wondrous phenomenon that I can’t commit to what, to me, would be a narrowing down to any one form of it in faith. I accept all faiths as splinters of a larger whole.

What I am intolerant of is any form of fundamentalism. I live on a site that has been occupied since the last ice age. I am half a mile from the radio telescope at Jodrell Bank. My friends are cosmologists, particle physicists, archeologists, historians, theologians – this chimney has heard conversations that you’d not believe! As soon as you get into quantum physics, you are in pure poetry.

And from that richness I feel it would be arrogant of me to say that I knew the truth.

Isn’t there something noble about seeking the truth all the same?

If there’s one reason for getting out of bed in the morning, it is that.

I can show you a flint hand-axe, half a million years old, that was dug up locally. I was holding the axe and – a eureka moment – through the window I could see (in the same shot, as it were) the radio telescope. And – another eureka moment – I logged on to see what the telescope was observing, and it was a quasar. The signals that were arriving at the speed of light at the moment I was holding that axe had already covered more than 97 per cent of their journey when that pebble was chipped. So, who am I to question theology?

There is a thread that runs through everything I’ve written, which is the importance of dreaming. A dream is not unreality. Treacle Walker is the only book where I feel I’ve got near to what I’ve seen

Although I have no religious faith, I don’t feel that I’m missing anything. I can see, let us say, the Bible as a great work of literature, a great distillation of wisdom, a great use of metaphor and myth – because for me metaphor and myth are the purest way to begin to appreciate reality – but it’s the view of (let me put it this way) an ape sitting on a piece of damp rock going round a minor star in an insignificant galaxy, which is one of, possibly, an infinite number of galaxies. (Though I’m wary of that word ‘infinite’. It scares me.)

At its simplest – and now I’m being banal – atheism is a belief system: you can’t prove it or disprove it. So, if I am asked, ‘Where do I stand?’, my answer is: I’m an optimistic agnostic. Intellectually and emotionally, I feel that without that gift of faith, which I acknowledge but have not experienced, the only honest position is to say: This ape on this bit of damp rock can’t know. Yet.

The ‘yet’ is important, though, isn’t it?

Yes! It’s essential.

I’m struck by your word ‘experience’. For you, belief is something that is experienced.

Yes.

You began your writing career with the legend of Alderley Edge…6See nationaltrust.org.uk/the-legend-of-alderley-edge.

It’s the only original work, I feel, that I’ve ever done. I heard it from my grandfather, who told it with authority. And I never said: ‘Is that true, Grandad?’ I think if I’d said that, he would have felt that he’d chosen the wrong person to tell the story to.

But when I went back to it as an adult, it fascinated me – and I discovered within it clues that led me to the evidence of the Bronze Age on Alderley Edge.7In 1953, he rediscovered an old wooden shovel that had been found in an Alderley copper mine in 1875. In 1993, it was carbon-dated to c1750BC by researchers at the Manchester Museum. The Edge is the earliest-dated metal-working site yet discovered in England. The legend mentions all the [local] sites where there is evidence of the Bronze Age, which suggests an oral tradition going back 4,000 years.

The legend of the sleeping hero contains the idea of a deferred apocalypse…

During the Second World War, when I was a child, I remember adults laughing and saying, ‘If that chap’s ever going to wake up, now’s the time – but he’d better have white tanks, not white horses!’ Which is a very nice combination of belief and disbelief.

Was there a reason why – unlike C S Lewis, say – you didn’t have a ‘last battle’ in your narrative?

There are analogues for the sleeping hero, right across the northern hemisphere – I think there are nine in Britain alone. And the question that intrigued me was: Why, in every version, after the sleeper begins to awake, does the mortal who finds him say: ‘Sleep you on!’?

The answer I’ve come up with is that it seems as though the sleeping hero is the last ace in our hand and while he’s asleep, he’s potential. Once we wake him, we’re finished.

As a writer, it would be bad intellectual business to close things down?

Yes! Fatal!

I don’t want to spoil Boneland8Published by Fourth Estate in 2012 for anyone who hasn’t read it; but, as I recall, its last words are: ‘Sleep now.’

I tend to forget a book when I’ve written it, so we’d have to go back to the text.

There is a thread that I see with hindsight running through everything I’ve written, which is the importance of dreaming. A dream is not unreality. Treacle Walker is the only book where I feel I’ve got near to what I’ve seen.

My mother brought me up to feel that if I conceded an argument, I was showing weakness. I have made a complete reversal – which is why I say that my one bugbear is fundamentalism of any kind

You return to the idea that the dream kind of exists alongside waking life?

Well, I don’t want to say what a book is about, because that is to limit it.

Another theme I have, another tub I thump, is: If a book’s worth reading, it should have an infinite number of interpretations. Perhaps not infinite, but each reading should be a creative act, making the work live on the page, new again, because of its interaction with the reader, who has their own personal biography.

And I’ve found evidence for that over the years. People have come up to me and said, ‘Your book frightened me to death!’ And then they tell me [which bit of it frightened them] and for me it was just a link – whoosh! – from one purple passage to another. And it’s the whoosh! that’s terrified them, and the two bits that excited me have [made no impression].

Are you happy as a novelist to give up control of the narrative once it’s out there?

Wholly. Wholly. I like to think that what I write is an open hand, not a pointing finger. ‘Is there anything there?’, not ‘This is what it’s about.’

You mentioned Dickens. It strikes me that, although you are generally elsewhere on the spectrum, there is something Dickensian about your most memorable characters, such as Gowther Mossock.9Who appears in both The Weirdstone of Brisingamen: A tale of Alderley and The Moon of Gomrath, published by Collins in 1960 and 1963 respectively.

He was a real man, an extraordinary man.

Another great influence on me [was a local miller,] a trickster who could always run rings round me. Once, he said to me (in the broadest of Cheshire speech): ‘Can you tell me, Alan, which side of the church do the yew trees grow on?’ I plundered my mind, all that I’d read about tree lore, and I said: ‘I give up.’ And he said: ‘They grow on the outside, don’t they?’

Then he said: ‘Fetch a tape recorder. I’m 80 years old and I know things that are in no books and are on no maps and I’m going to tell you them.’ I got 20 hours on tape – I was nearly in tears. I said: ‘Why me?’ And his answer was: ‘You’re the only one of us left with the arse hanging out of his britches.’

That’s a vivid image!

It translates as ‘I trust you.’

You are bipolar and you’ve written quite openly about your own experience of mental illness, in essays such as ‘Inner Time’.10Collected in The Voice that Thunders (Harvill Press, 1997) Was it unusual for someone of your generation to be so candid?

From the reactions, I think it was fairly unique at the time. I didn’t do it out of any sense of duty, that ‘Somebody’s got to say it.’ It was just a way of making it clear to myself, I suppose, because in a way – trying to be objective about myself – I write in order to answer questions I can’t resolve intellectually.

One of my favourite quotations, from Yeats, is: ‘We make out of the quarrel with others rhetoric, but out of the quarrel with ourselves poetry.’11From ‘Anima Hominis’, Essays (Macmillan, 1924) I wonder whether in that sense some of your work might be a kind of poetry…

Oh, it is. No doubt.

In my early childhood, my mother brought me up to feel that if I conceded an argument, I was showing weakness. I have made, through my lifetime, a complete reversal. Which is why I say that the one bugbear I have is fundamentalism of any kind.

One way of [writing serious fiction] is observational; the other way is visionary, a poetic way of looking at the world. It makes quite different demands on the writer – it has to be dragged out of the depths

We’ve talked a little about class and its impact on your life. Has politics played any part in what you do?

I’ve been fortunate to live in a time, place and culture where I can be apolitical. And what made me apolitical was ancient history. In the past, the Oxford course I took has been the passage to No 10 Downing Street,12Of the 28 British prime ministers who went to Oxford, five studied classics: Robert Peel, William Gladstone, H H Asquith, Harold Macmillan and Boris Johnson. but for me it had the opposite effect. I became aware in my teens that I was not a political animal; then I did National Service, and in my fourth term at Oxford the Suez Crisis13wikipedia.org/Suez_Crisis blew up and I was on 12-hour standby, which made me realise that if they said, ‘Come!’, I would not.

And I realised that I was having a wonderful time – and suddenly it might all end, in a literal flash, in four minutes’ time.14wikipedia.org/Four-minute_warning That brought me up short, and it started me thinking: ‘I didn’t ask to be here.’ (I was on a kind of conveyor belt: I’d gone to Oxford because that was what you did next.) ‘Am I a scholar? Am I an academic? What am I? It’s time to stop fooling around.’

A lot of this was unconscious, but I had a Damascene moment on 20 August 1956. I was at home in Alderley and I realised that I was finite and I’d got to make my mind up. I was sitting at a bus stop looking across the road at a wall that my great-great-grandfather had built, and I thought: ‘I’ve got to continue that. Here. This is what I know.’

That for me was an epiphany. Am I making sense? I had thought that Oxford was bliss, but by the end of the first term it had become a citadel, floating in the clouds, and there was no world outside it!

You still stayed on at Oxford for another three terms before you quit. It was obviously hard in a way to leave it behind.

Yes. But that wall made it no contest. Because it made concrete all those abstract, over-thought thoughts that had been going on for a long time.

You knew that your work somehow was going to be in this place?

Yes. As my grandfather used to say: ‘If the other fellow can do it, let him!’ Was I going to become just another Oxford classicist or was I going to do something else? And in asking the question I knew it had to be ‘something else’ – and that was very frightening.

I remembered a Sixth Form essay: ‘The only free man is the artist. Discuss.’ So, I thought: ‘That’s what it’s going to be. I’m going to be free. My hands are no use, but I do have an affinity with language. I know what I’ll be: I’ll be a novelist.’ It is the most idiotic thought I have ever had in my life!

In ‘Inner Time’, you talk about humankind as ‘the boundary crosser’…

It’s the description of Grendel in Beowulf: mearcstapa, ‘boundary-strider’.

Is it significant that the very form you chose – fiction, and (in part) fiction that engages with myth and folklore – itself crosses boundaries?

H’mm. I don’t know. But Jung came up with an explanation which I find very attractive. He divided the writing of fiction into two areas (I’ve changed his terminology slightly).

In writing serious fiction, the writer is trying to understand and to communicate. And one way of doing that is what I would call the ‘observational’, which is concerned with the whole of human existence, its joys, its sorrows, its problems. And so you get Jane Austen.

The other way is not observational but visionary, and that’s far closer to dreaming. It is a poetic way of looking at the world, and it makes quite different demands on the writer. It has to be dragged out of the individual’s depths, the depths of the whole culture – the collective unconscious, if you accept the term – and therefore it’s far harder to do.

You make it sound almost like archeology.

Yes. There’s something here that’s saying: ‘Let’s have a closer look, strip a little bit off! Oh, there’s something emerging. Oh, I see what it is: it’s Troy…’

It’s a mysterious process because (and I speak only for me here) I don’t make things up, I find them. Or they find me. And it can be terrifying.

Your writing style is very stripped-back…

There is a very strong influence on my writing from the cinema, because as a child, besides reading, I went to the cinema twice a week, to watch anything. B-movies can be very rich pickings! Paradoxically, language is the medium of my expression but I must remove the words as far as possible, so that they don’t obscure the purity of what I’m looking at.

I have a marvellous editor, who is ruthless, and he says that I have spent my life trying to write a blank page.

You don’t use a lot of adjectives or adverbs. It sounds as if that is very deliberate.

It is, yes. If a word is not needed, get rid of it! Adjectives have to earn their keep, and adverbs have to plead for their lives!

I still have the exercise book where, when I was nine, I wrote in a composition ‘The window was opaque’ and there’s a big tick next to ‘opaque’. That’s a word I wouldn’t use now. If I had to make that point, I’d say: ‘He couldn’t see through it.’

Which focuses on the subjective.

Yes. And also on Germanic rather than Romance vocabulary – which is why English is so rich and so devilish, because it has those two influences.

You’ve been very deliberate in the way you’ve picked your projects. There aren’t 13 novels set in the world of the Weirdstone, for example.

When The Moon of Gomrath was published [in 1963], I remember a Collins rep said: ‘Eleven more and you’re suited!’ But I’d already had enough of those two blasted children.15The twins Colin and Susan. Colin eventually reappears as an adult in Boneland (HarperCollins, 2012). I thought: I’ve changed; they won’t.

I owe my grandad a lot.

Why do you say that?

‘If the other fellow can do it, let him!’

Treacle Walker took off, like no other book. It wrote itself in a matter of months. It brings together everything I’ve written, in 15,000 words

You’ve written 10 novels, a volume of essays and a memoir and rewritten a lot of folktales. It’s a large body of work. What compels you now to keep writing? It must be something you either want or feel compelled to do.

I can’t give you an honest answer, because I can’t pick up a bucket when I’m standing in it. I can be clever-clever and hypothesise. For instance, my inheritance on one side was manual craft and perfectionism. My father was a painter-and-decorator and if he was asked to do a job he would say: ‘Who’s the plasterer?’ He told me once: ‘If the plasterer doesn’t get it right, people are going to say I can’t hang wallpaper.’ And this connects. As I saw it, my father was following his father saying: ‘If the other fellow can do it, let him!’

The other curse my grandfather put upon me was: ‘Always take as long as the job tells you! It will be there when you’re not and you don’t want people saying: What fool made that?’

Hence, your emphasis on craftsmanship…

I inherited it – not consciously. It could be genetics, or it could just be the air I breathed.

Tell me about the genesis of Treacle Walker.

This says more than any other thing how my imagination works. A friend of mine who’s a particle physicist was questioning me into the early hours. He could not understand where I got my ideas from (and I couldn’t get across to him that I didn’t know, either). Being a physicist, he’s faced with explaining something that’s there and what was bugging him was that he couldn’t see that anything was there for me to see.

The next day, we were walking over an Iron Age hill fort above Huddersfield and he told me a piece of local history. In the Twenties and Thirties, there was a tramp who worked the farms on the moors, doing odd jobs in exchange for food. He had a reputation as a healer and he claimed to be able to heal ‘all things except jealousy’. And I thought: ‘That’s a sophisticated thought for a tramp!’ His name was Walter Helliwell but he was called ‘Treacle Walker’, my friend told me. ‘Isn’t that a strange name?’

And that gave you the germ of a book…

And then I found, through the long conversations we’d had, that the book took off, like no other book. It wrote itself in a matter of months. My friend has read it and he says that he’s seen his subject through a novelist’s eyes and that, for him, it’s a new vision of quantum physics. It’s not; I’ve not done anything except look in a different way at different states and put them into a story where time collapses, and the whole thing takes place in no time – or, rather, not in time as we see it.

It brings together everything I’ve written, in 15,000 words.

To make sure you hear of future interviews in this series, follow High Profiles on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

| ⇑1 | Joseph Sparkes Hall, in 1837. He invented the elastic-sided boot and wrote ‘a history of boots and shoes’, The Book of the Feet. |

|---|---|

| ⇑2 | By Leo George Chiozza Money, published in 1903 |

| ⇑3 | Published by Fourth Estate on 28 October 2021 |

| ⇑4 | At Oxford in 1956, he was to play Mark Antony in Antony and Cleopatra. Ann Cook (who he married later that year) played Cleopatra and Dudley Moore played Enobarbus. |

| ⇑5 | Published the previous year by Collins |

| ⇑6 | See nationaltrust.org.uk/the-legend-of-alderley-edge. |

| ⇑7 | In 1953, he rediscovered an old wooden shovel that had been found in an Alderley copper mine in 1875. In 1993, it was carbon-dated to c1750BC by researchers at the Manchester Museum. The Edge is the earliest-dated metal-working site yet discovered in England. |

| ⇑8 | Published by Fourth Estate in 2012 |

| ⇑9 | Who appears in both The Weirdstone of Brisingamen: A tale of Alderley and The Moon of Gomrath, published by Collins in 1960 and 1963 respectively. |

| ⇑10 | Collected in The Voice that Thunders (Harvill Press, 1997) |

| ⇑11 | From ‘Anima Hominis’, Essays (Macmillan, 1924) |

| ⇑12 | Of the 28 British prime ministers who went to Oxford, five studied classics: Robert Peel, William Gladstone, H H Asquith, Harold Macmillan and Boris Johnson. |

| ⇑13 | wikipedia.org/Suez_Crisis |

| ⇑14 | wikipedia.org/Four-minute_warning |

| ⇑15 | The twins Colin and Susan. Colin eventually reappears as an adult in Boneland (HarperCollins, 2012). |

To find out more about the agenda behind our interviews, read our manifesto. To access our archive of more than 260 interviews, see the full list.

Biography

Alan Garner was born (in the front room of his grandmother’s house) in Congleton, Cheshire in 1934 and grew up in the nearby village of Alderley Edge. He was educated at Manchester Grammar School, the first member of his family to receive anything more than a basic education. In 1952, he was said to be ‘the fastest schoolboy sprinter in Great Britain’. He then did two years’ national service in Woolwich as a subaltern in the Royal Artillery.

In 1955, he went to Magdalen College, Oxford to read classics, but quit after four terms to devote himself to writing. He supported himself for some years by working sporadically as an unskilled labourer and, later, as a freelance researcher and interviewer for television.

In 1957–8, he bought and renovated Toad Hall, a Late Medieval building in the village of Blackden, eight miles from his birthplace. In 1970, he purchased a second timber-framed building, the Old Medicine House, and had it moved to the same site from Wrinehill in Staffordshire. He co-founded the Blackden Trust in 2004 to ‘preserve, explore and share’ this site.

His first novel, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen: A tale of Alderley, was published in 1960. It was followed by a sequel, The Moon of Gomrath (1963); three further fantasy novels, Elidor (1965), The Owl Service (1967) – the first book ever to win both the Carnegie Medal (in ’67) and the Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize (in ’68) – and Red Shift (1973); the ‘Stone Book Quartet’ of four novellas: The Stone Book (1976), which won the 1996 Phoenix Award, Tom Fobble’s Day and Granny Reardun (both 1977) and The Aimer Gate (1978); two further novels, Strandloper (1996) and Thursbitch (2003); and Boneland (2012), which concluded the Weirdstone ‘trilogy’. Treacle Walker was published by HarperCollins on 28 October 2021.

He is also the author of The Guizer: A book of fools (1975), Alan Garner’s Fairytales of Gold (1979), The Lad of the Gad (1980), Alan Garner’s Book of British Fairy Tales (1984), A Bag of Moonshine (1986), Once Upon a Time (1993) and Collected Folk Tales (2011). Other minor works include The Old Man of Mow (1967), the dance drama The Green Mist (1970), The Breadhorse (1975), Jack and the Beanstalk (1992), The Little Red Hen (1997) and The Well of the Wind (1998). His books have been translated into many languages, including Basque, Czech, Japanese and Russian.

He adapted The Owl Service for Granada TV in 1969 and Red Shift for BBC1 in 1978, and wrote the screenplays for the TV documentaries Places and Things (1978) and Images (1981). He has besides written six plays – Holly from the Bongs (1966), Lamaload (1978), Lurga Lom and To Kill a King (both 1980), Sally Water (1982) and The Keeper (1983) – and the libretti for three operas: The Bellybag (1971), with music by Richard Morris; Potter Thompson (1972), with music by Gordon Crosse; and Lord Flame (1995), which was never scored.

A collection of his essays and public talks, The Voice that Thunders, was published in 1997, and his memoir Where Shall We Run To? in 2018.

He was runner-up for the biennial Hans Christian Andersen Award in 1978. He won the British Fantasy Society’s Karl Edward Wagner Award in 2003, and a World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement in 2012.

He was appointed an OBE for services to literature in 2001. He was elected a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London in 2007 and of the Royal Society of Literature in 2012, and holds honorary doctorates from Huddersfield, Manchester Metropolitan, Salford and Warwick Universities.

He has three children with his first wife and two with his second, whom he married in 1972.

Up-to-date as at 1 November 2021