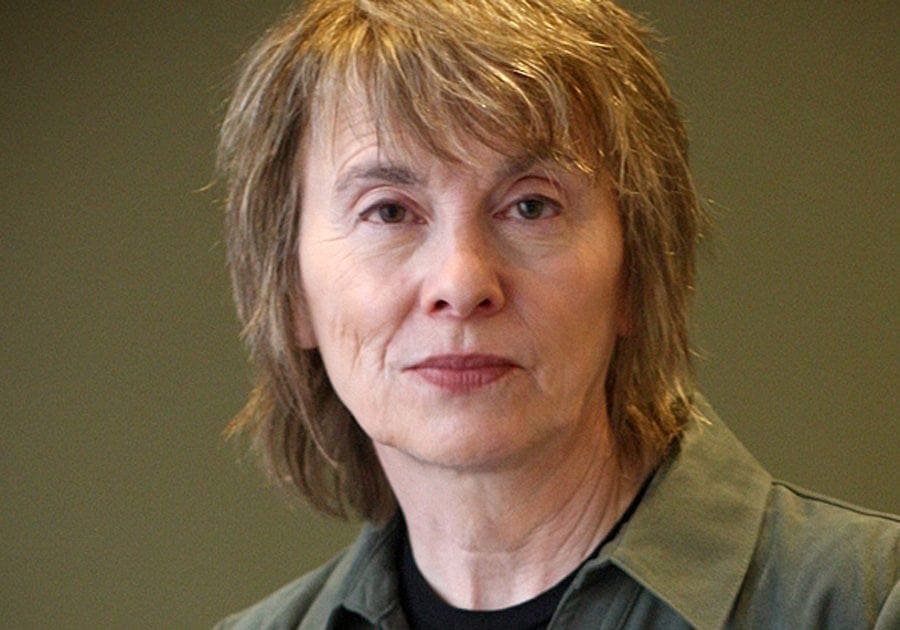

Camille Paglia

is a US social critic, cultural commentator and ‘dissident feminist’ with a gift for creating storms of controversy. Harriet Harris got her number on 11 September 2008.

‘I know from experience that it is fiendishly difficult to catch someone’s real voice, but this really does catch mine,’ she told us later. ‘I loved it.’

Photography: Michael Lionstar

Could we start by talking about the intellectual passions of your life? Were art and literature your first loves?

My entire system of ideas was shaped by the Italian-American immigrant experience. My mother and all of my grandparents were born in Italy – they came over to work in the shoe factories in Endicott, a very grey industrial village in upstate New York that was originally very Protestant and ethnically very homogeneous.

Right from the start, I had this intense sense that the church where I was baptised, St Anthony of Padua Church, was a kind of temple of culture – the gorgeous stained-glass windows and polychrome statuary were a sharp contrast with the then very bland, conformist world of late 1940s and 1950s America. Endicott is in the ‘snow belt’ and the number of days there without sunlight is very high, and so the luminosity – I might say, hallucinatory luminosity – of the stained glass and the statues had the most amazing impact on my brain. And the iconography of those statues also – every one posed with a symbol or in a representative posture.

My favourite of all was St Michael the archangel in his beautiful silver armour, his flowing crimson cape, trampling on the Devil with his sword uplifted. I found it a very heroic and stimulating image. At a time when one was expected to be a good little girl and behave in a very feminine way, I adored St Michael with his armour and his sword. He was my patron saint.

I’ve never lost that sense – and I still argue it constantly – that the visual sense and the language of the body are primary ways of communication, and that is why, though I’m a literature professor, I have waged a fierce battle against post-structuralism over the last 20 years, because I feel that it’s absolutely absurd to think that the only way we know anything is through words. My earliest thoughts were visual and my earliest responses were to colour and line and gesture.

I developed a way of looking at things that was a kind of transfer of religiosity from the church to Hollywood. It became the foundation of my way of seeing Western culture

I then made a connection between the lavish imagery of the cult of the saints in that church and the movie stars I saw – you know, we didn’t have that much money and we saw very few films, but the ones I did see had a tremendous impact on me: Walt Disney’s Snow White and Show Boat, starring Ava Gardner, and then the original Moulin Rouge and so on. I developed this way of looking at things that was a kind of transfer of religiosity from the church to Hollywood – and that became the foundation of my way of seeing Western culture.

Eventually I would elaborate this in my first book, Sexual Personae.1Sexual Personae: Art and decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson (latest edition: Yale University Press, 2001) Its overarching argument is that Judeo-Christianity never did triumph in the West, OK? Rather, it’s been challenged periodically (and at times defeated) by the eruption of paganism: in the Renaissance, in Romanticism (which I view as an upsurge of the buried Dionysian elements in Greco-Roman culture) and then the third challenge, modern Hollywood, with its motifs of sadomasochistic eroticism and pornography and so on.

The Christianity you describe is passionate and earthy. Why do you think it was ‘challenged’ by paganism?

Well, certainly one can see evidence that Christianity absorbed pagan influences. Certainly, the Reformers were convinced that Christianity had been contaminated by pagan influences, the cult of Mary and the saints. I think that modern scholars have proved them right. It seems that Mary was simply a version of Isis – the people of the countryside (which is what ‘pagans’ means) would not let their goddess go.

But I think that the main issue is sex. Christianity sees nature as a fallen realm, a corrupt realm which we must rise above. You know, there is a denigration of the body and its impulses and of sensual life. One sees that in medieval depictions of the Garden of Eden: the figures of Adam and Eve are crabbed and awkward. The flesh is not something to admire. It’s certainly not glorified in the way it was in Greek and Roman sculpture.

For me, that is a very large issue. That is why early on I was in conflict with my fellow feminists over this issue of nudity in popular culture. In the 1980s, the period of what I would call ‘Puritan feminism’, any representation of a female nude was regarded as inherently degrading to women, making the female passive to the male gaze. I waged a long war about that.

I am very uncomfortable with that fear of the male gaze. If you want to argue that every representation of a nude woman is inherently degrading, how do you explain what’s going on in the gay male world? There’s not a gay man anywhere who would say that a depiction of a nude young man for the pleasure of an older gay man is degrading. On the contrary, every ageing gay man would say: ‘No, this beautiful nude young man is superior to me. I’m looking up to him.’

(That’s not to say that there isn’t degradation in some kinds of pornography – I wouldn’t deny that.)

Do you think that the fine arts in the Western Christian tradition have finally run out of steam?

I had a lot of run-ins with the Irish nuns who taught us. The last straw came when I raised the question: ‘If God is all-forgiving, is it possible he will ever forgive Satan?’

Oh, I think all the fine arts are at a dead end right now. Certainly Christian art is. In the United States at least, there is a terrible sentimentality in Christian art.

Can you suggest a remedy?

My remedy for everything is always to introduce it into the curriculum at the very earliest stage. I think you’ve got to teach religion as well. I always tell my classes – always without fail – that a part of their education is to see The Ten Commandments.21956, dir Cecil B DeMille Here’s pagan Hollywood giving a worthier overview of religion than liberal students from good homes are getting at the élite schools, where they’re being taught Michel Foucault instead. It first hit me in the 1990s when I mentioned the Garden of Eden and only one or two students in the entire class knew what I was talking about. I was horrified.

Why did you eventually reject the church?

I had a lot of run-ins with the Irish nuns who taught us religious education, and the last straw came when once I raised what still seems to me a very interesting question: ‘If God is all-forgiving, is it possible he will ever forgive Satan?’ The nun went absolutely apoplectic. She turned deep red and yelled at me for even daring to ask such a question. Well, that was it as far as I was concerned. In my view, there was no room in the American Catholic church for an enquiring mind.

And of course the nuns then were obsessed with sex. You know, the paradigmatic saint was St Maria Goretti, who chose to be stabbed to death rather than surrender her virginity. She was the ultimate symbol – as was St Thérèse of Lisieux. I found them both very dreary role models compared with St Michael. I later learnt about the far fierier – and, of course, more intellectual – St Teresa of Avila, who became a real role model for me.

Oh! I should also mention the Legion of Decency, founded by the Catholic bishops back in the 1930s and still going strong in the 1950s. There was a list posted in the foyer of the church every week saying which movies in town could be seen by Catholics. The one I will always remember was Baby Doll,31956, dir Elia Kazan which was based on a screenplay by Tennessee Williams (who a little later became one of my very favourite writers of all time).

This was completely and absolutely condemned, on pain of hell or whatever. It’s a very lewd storyline, with the seduction of what appears to be an under-age girl, and the advertising campaign for it was extremely provocative. Even today, I think, there would be a tremendous backlash against it. The reason for the controversy seems obvious to me now – the whole thing was quite perverse – but at that time, seeing this waving of hellfire at the name ‘Baby Doll’ (and this was a pivotal moment for me, along with the nun refusing to answer my question about Satan), I identified strongly with the paganism of Hollywood and not with the Catholic church.

Do you think the Western church is too obsessed with sex in terms of issues of homosexuality and gender?

I’m known as an atheist who immensely respects religion. I think it’s very bad for a culture to imagine that there is enough sustenance in the secular worldview to help people along in life

I think the issue of homosexuality is certainly a flashpoint. As an open lesbian myself, I fail to understand how so many gay Catholics want the church to change its doctrine to accommodate them. In my view, if people want to form a splinter church, that is perfectly justified in the Protestant tradition, so go ahead and do it!

To try to project this fantasy that the Bible does not condemn homosexuality seems to me absurd. The arguments are so weak! People say things like, ‘But look, there are so many proscriptions in the Bible that are now ignored, about food preparation and so on. Why can’t this one be ignored?’ My reply is: ‘Because issues of sexuality and identity are rather more central to the Judeo-Christian tradition than is food preparation, OK?’

You also hear in America – all the time on TV, it’s really so sloppy – that Jesus said, ‘Let him who is without sin cast the first stone!’ And of course they’ve completely omitted the next sentence: ‘Go, and sin no more!’4See John 8:7–12.

I think people want the church to be a kind of foster family, OK, and they become very uneasy about questions of theological doctrine. But if one accepts the Bible as the word of God, I don’t think one has the right to cherry-pick, merely because one feels merciful toward one’s fellow gay citizens. It’s called ‘cafeteria-style religion’ in the United States, when you decide which precepts you’re going to follow and which not. In the same way, many heterosexual American Catholics flout the church’s opposition to birth control.

I can say this very blasély as an atheist, obviously.

How do you characterise your attitude to religion now?

Well, I’m known as an atheist who immensely respects religion. As someone raised in the 1950s, I feel extremely claustrophobic about organised religion, but I think it’s very bad for a culture to imagine that there is enough sustenance in the secular worldview to help people along in life, OK? I feel that religion and art, in tandem, present a very complete worldview – not just later on, as tragedies begin to strike, but for the long haul. But I do have a kind of eclectic, syncretistic view of religion.

You have argued that the Bible should be part of the curriculum because it has had so much influence on literature, and hymnody should be because it helps us to understand Western music. Could they be of benefit to students in other ways as well?

I do feel that the Bible – the Old and the New Testament – is one of the greatest books ever written. I don’t feel it was divinely inspired, but that’s just my personal view; but I think it is an incredible collection of, you know, poetic insights into human life.

If one accepts the Bible as the word of God, I don’t think one has the right to cherry-pick, merely because one feels merciful toward one’s fellow gay citizens

I feel that religion gives one the long view. It gives perspective on oneself. I feel that there is a kind of cosmic vision that comes from the study of any religion – a wider view. I think the most controversial sentence I have ever written5In Sexual Personae was ‘God is man’s greatest idea.’ I do feel that people who have no feeling for God, the idea of God, are to be pitied. If you can’t even understand the idea of God, if you’ve not lived with it, even to reject it later on, I do think there’s a limitation of imagination.

I’m interested in studying all the different ways God has been defined. I find it very inspiring. Metaphysics no longer is a prestige area of study in philosophy. Even science has lost a lot of its sense of awe at the mystery of existence. Scientists have become essentially stewards of the machine. They’re technocrats now, rather than big thinkers. I mean, Einstein certainly thought in much larger terms than our contemporary scientists.

What do you think of the ‘new atheists’, such as Richard Dawkins, who call on us to kill our invisible gods?

Well, yes, there’s been quite a fad for atheism recently. I know that Dawkins was well established in England as an atheist, but I do believe that I was the first of the public intellectuals in America in the last 20 years to publicly say I was an atheist. I think I’m the one who sort of caused that fashion over here, though people may not want to admit it. After that, you began to get writers in leftist magazines saying ‘I’m an atheist! I’m an atheist!’ People didn’t dare to say that before.

Now, the reason I felt that I could say it was because I don’t have any contempt whatever for religion or religious people. Unfortunately, that is now rampant. There is a great deal of contempt for religious people in my own party, the Democratic Party, which I’m constantly speaking against. I think it has been an absolute disaster for my party, and we may be on the point right now of losing another election because of it.6In fact, Barack Obama won the US presidency that year with 52.9% of the vote. We’re in the middle of a tremendous controversy here over the Republican candidate for Vice-President, Sarah Palin. I’m just dismayed that people are trying to portray her as a dangerous religious extremist.

Dawkins is certainly a very formidable writer and thinker, but I don’t think that the books by atheists over here have been particularly strong. Christopher Hitchens’ book [God Is Not Great]7God Is Not Great: The case against religion (Atlantic Books, 2007) was an absolute shambles – he knows absolutely nothing about the history of religion, and I mean nothing. The chapter titles are quite superb – I mean, the book had the makings of a really important contribution to intellectual history – but it’s like he sold it on the basis of that outline and then just didn’t spend enough time on it.

But anyone who speaks dripping disdain of religion or religious people does not have my respect. I find it so adolescent – to retain that tone into your thirties and forties I think is a symptom of a very undeveloped mind.

And Hitchens’ argument that religion is the source of everything negative in the history of mankind – what nonsense! What absolute nonsense! Religion has been overwhelmingly a positive force in giving people a moral frame, for heaven’s sake!

What are the values I aim to live by? How interesting! No one’s ever asked me that. Well… There’s the idea that one proves one’s value by working…

What are the values that you aim to live by?

Values I aim to live by? How interesting! No one’s ever asked me that. H’mm. Well… You know, I was raised in an originally working-class family that then became middle-class. My father was the first of his family of 10 to go to college and went on to become a professor. So, my family is very rooted in the working-class value of hard work, and there was great disdain for people who were lazy. I’m afraid I’m probably something of a workaholic – I’m just constantly in motion.

So, there’s that, the idea that one proves one’s value by working. What else? I try to do my absolute best in everything I do, which means that there’s no slacking. Alas, what that means is that for me writing books is a very, very laborious process. I take them very seriously – as opposed to articles – to the despair of my publishers, who would prefer that I turn out a book a year.

What else? I think one should publicly take responsibility for anything one has done that has had damaging consequences. This comes from the Catholic tradition of confession, of course.

What else? I try to be absolutely honest, to the point perhaps of a lack of diplomacy, alas. The last two weeks have been absolute hell, because I had to write a huge article for Salon.com about Sarah Palin.8www.salon.com/2008/09/10/palin_10 Nothing have I ever dreaded more in my life. It ended with me talking about how I thought through the ethical consequences of abortion. Even though I am completely pro reproductive rights, I feel that my party has been very ethically obtuse in the way it has treated abortion as if it is simply a surgical procedure without an effect on a real human being – the aborted foetus.

It has been like a bombshell. The article was posted barely a day ago and already there have been more than 800 letters to the editor, and 700 to me. People are in an absolute fever. It took me aback, but, you know, I had to say what I thought, no matter what the consequences.

Where does your confidence come from? John Updike said of Sexual Personae that you weary the reader who is looking for doubt and hesitation in your voice.

Well… I don’t follow astrology as much as I did in college, OK – another of those pagan systems I have found very useful – but I have always had this tremendously combative, wilful personality and it was not until I read the description of my birth sign, which is Aries, that I began to think I should attribute my warrior personality to my birth. Everything about me is like an Aries woman. (Bette Davis and Joan Crawford also were Aries.)

I’ve always been confident of my first impressions. I’ve always felt I have a kind of intuition. I see and hear things that other people seem oblivious of

My parents, the way they raised me, certainly wanted me to think for myself – at the start, at any rate. Later on, when my ideas disagreed with theirs, they weren’t quite as happy about it.

I’ve always been confident of my first impressions. I’ve always felt I have a kind of ability to pick up things, an intuition; I think that my powers of observation have always been very keen, and I see things and hear things that other people seem oblivious of. It’s nothing oracular, it’s just things they don’t notice. Maybe it’s also my Catholic background, but things come to me as if it’s a revelation and I try to tell other people and they don’t see it, and so I become kind of evangelical about it and over-excited, and then they don’t see it even more.

That’s probably why I graduated to being a writer, because if I get it down on paper, people will have to deal with it. I just sort of throw it at them. Here it is, here’s the bombshell, deal with it! I don’t think I’m particularly convincing as a person. I mean, I’m not very prepossessing: I’m a small, fast-talking woman – and the serious thinkers were always tall, slow-speaking men.

In the old country, I would have been a nun. No doubt about it: I would have absolutely become a nun. I mean, there are religious in my family – there’s a nun, an abbess, a sexton at the Vatican, a priest, a bishop. Both sides of my family have religious there. And I feel, shall I say, very inspired not only by St Teresa of Avila but also by St Thomas Aquinas. He was born very near my mother’s town, so we’re probably related.

Could you have coped with the cloistered life?

Well, when I said this once in the family gathering, my cousin the nun said: ‘You would have had one big problem: obedience.’ And that is true! But so many of the nuns were rather fractious. St Teresa of Avila was a rabble-rouser and a troublemaker who defied the hierarchy. So, I identify with that as well

This edit was originally published in the November 2008 issue of Third Way.

To make sure you hear of future interviews in this series, follow High Profiles on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

| ⇑1 | Sexual Personae: Art and decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson (latest edition: Yale University Press, 2001) |

|---|---|

| ⇑2 | 1956, dir Cecil B DeMille |

| ⇑3 | 1956, dir Elia Kazan |

| ⇑4 | See John 8:7–12. |

| ⇑5 | In Sexual Personae |

| ⇑6 | In fact, Barack Obama won the US presidency that year with 52.9% of the vote. |

| ⇑7 | God Is Not Great: The case against religion (Atlantic Books, 2007) |

| ⇑8 | www.salon.com/2008/09/10/palin_10 |

To find out more about the agenda behind our interviews, read our manifesto. To access our archive of more than 260 interviews, see the full list.

Biography

Camille Paglia was born in Endicott in 1947 and attended William Nottingham High School in Syracuse, New York.

She read English at Harpur College (latterly the State University of New York at Binghamton), graduating in 1968. She gained her doctorate from Yale in 1974.

From 1972, she taught literature at Bennington College in Vermont, until she resigned in 1979. She then taught for a while at Wesleyan University in Connecticut (where she also taught night classes at the Sikorsky helicopter plant) and in 1981–84 was a visiting lecturer at Yale.

In 1984, she joined the faculty of the Philadelphia College of Performing Arts, which merged in 1987 with the Philadelphia College of Art to become the University of the Arts. In 2000, she was appointed University Professor of Humanities and Media Studies.

She wrote a column for Salon.com from its inception in 1995 until 2001, which she resumed in 2007. She is a contributing editor at the magazine Interview.

She has written numerous articles for publications around the world, and has lectured and broadcast extensively both in her own country and abroad.

Her first book, based on her dissertation, was Sexual Personae: Art and decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson (1990), which was nominated for a National Book Critics Circle Award. It became a bestseller, as did her subsequent collections of essays, Sex, Art and American Culture (1992) and Vamps and Tramps (1994), and her studies of ‘43 of the world’s best poems’, Break, Blow, Burn (2005). She is also the author of The Birds, an analysis of Alfred Hitchcock’s film of the same title published by the British Film Institute in 1998.

She has lived with her partner for 15 years, and adopted her newborn son in 2002.

Up-to-date as at 1 October 2008