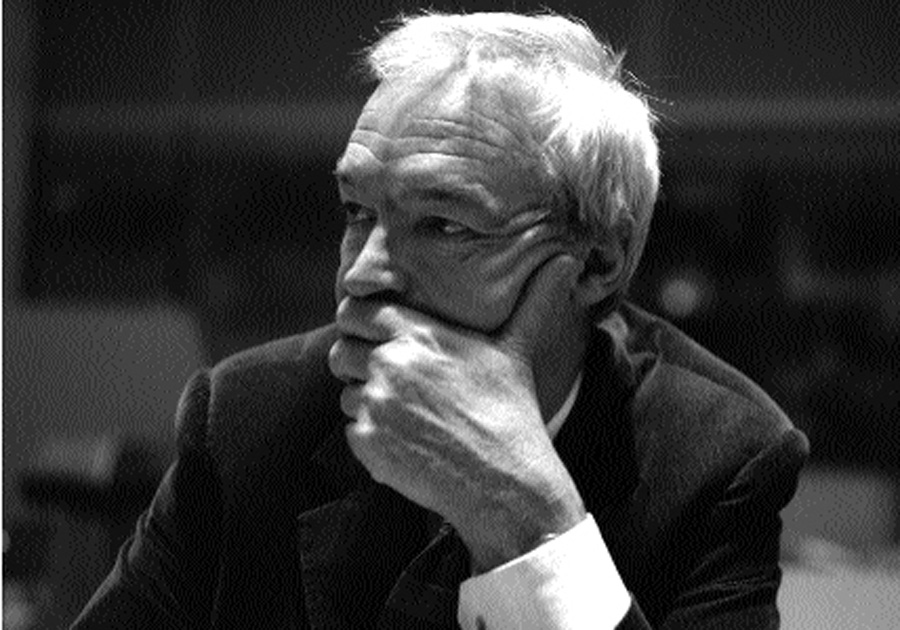

Jon Snow

‘is the closest thing we have to a modern-day George Orwell,’ the Independent declared in its review of his autobiography, Shooting History.

Huw Spanner met the veteran reporter at ITN House in central London on 16 November 2004.

Photography: Andrew Firth

Your autobiography1Shooting History: a Personal Journey (HarperCollins, 2004) tells some wonderful anecdotes about your childhood, but I’m not sure that it discloses much about the values that were instilled into you as you were growing up.

Well, to some extent they were the predictable values that flowed from an Anglican household whose head was a cleric. We had prayers every morning, with a Bible reading and the collect for the day, and on top of that I was a chorister at Winchester Cathedral and so I had five years of intense brainwashing courtesy of the Anglican Church Inc.

The general moral code that was imparted to me was something from which I think I haven’t departed a great deal. But as life progressed beyond 20 I began to realise that a lot of other faiths and philosophies embraced what is actually a pretty logical set of values.

Back then the Church of England was still very much the Tory party at prayer, wasn’t it?

Oh, definitely, all the way. But it was really also a business, rather before the era of business, and my father was really management in the corporation. He was only a straightforward cleric (although he happened to be headmaster of a public school as well), but it was absolutely assumed that he would clamber up the hierarchy very fast and would get a deanery or a bishopric or a grand canonry. And so it proved. Of course, in those days progression in the Church of England was courtesy of who you knew, and he made sure he knew exactly the right people. It was straight out of Barchester.

You are not a Christian yourself, are you?

I wouldn’t say that. I wouldn’t say that. But I think it’s a brave man who says he is a Christian. I mean, I’m not a rejectionist – and I get a great deal out of the Christian faith; but I wouldn’t yet be able to say I was a Christian. I think that’s a pretty big statement. It assumes all sorts of behavioural characteristics which I’m not sure I can claim.

Would you ever pray, for example?

I’m a panic prayer, but I don’t think that counts. I mean, God (if he’s up there) is going to say, ‘Hang on, mate! I don’t hear from you for six months and then all at once…’

Well, I contemplate. What is prayer?

When [in 1978] you were in a Malaysian prison with a possible 20-year sentence for aiding and abetting illegal immigration hanging over you, did you pray?

Oh yes. I’m a panic prayer, there’s no question about that; but I don’t think that counts. I mean, God (if he’s up there) is going to say, ‘Hang on, mate! I don’t hear from you for six months and then all at once…’ No, prayer is an engagement and I wouldn’t say that I’m engaged.

What I would say is that I go to church at least once a month, and I go into ecclesiastical buildings much more regularly than that, and I like to contemplate. If I’m sitting through a service, I let it wash over me. I like the form of words, I like the space and the silence of the building. There’s a whole lot of things the church is able to provide me – though I must say the odd mosque can also provide them, and the odd synagogue, too. I’m simply more familiar with the Christian, er, process.

There sounds a lily-livered, wishy-washy sort of chap! But I am not a rejectionist.

The experience that really radicalised you was the year you spent with Voluntary Service Overseas at the age of 20. How would you sum up its impact on you?

Absolutely massive. Totally profound. I had lived a very sheltered, privileged life and suddenly I was plunged into the bush in Uganda, into a Catholic mission school 250 miles from the capital.

I encountered a whole other world, a world I had no idea existed. I experienced real material poverty and yet fantastic richness of extended family, and these were contrasts from anything I had ever known in England. It made me realise that we had a great deal that they did not have, that they actually had a great deal that we did not have and that we perhaps had some obligations towards each other. Oh, I don’t think it’s difficult to see that so stark a contrast would have some effect on you, unless you were a block of stone. I was a sort of compressed, unimaginative Tory when I went out there and I came back a rebel.

And that was presumably reinforced when you went to work for Lord Longford –

At the New Horizon Youth Centre, which was a day centre for homeless teenaged kids. That was not so much about poverty as about utter individual personal devastation, a complete breakdown of the soul – and a breakdown of the extended family. To be exposed to 17-year-olds dying, dying of either hypothermia or drug use, was very shocking. I was still only 21, 22.

You were a bit of an agitator at university – you were directly responsible for getting the chancellor to resign. Are you embarrassed now by that radicalism?

Not remotely!

You’re proud of it?

Absolutely. I am perhaps slightly embarrassed about the formlessness of it, and the lack of ideology; but I don’t think in that sense I’ve changed. I’m still a bit wishy-washy. Perhaps it’s a bit like one’s faith.

Most people move to the right politically as they get older. That hasn’t happened to you?

I don’t think politically I’m any different from what I was when I came back from Uganda. Which was that I was not a joiner, I was somebody who judged each cause on its merits. You know, I never became a Trot or an International Socialist or anything. Or a fundamentalist Christian.

It’s very easy to dismiss people or things as evil or the work of the devil. Words like ‘terror’ and ‘terrorist’ are an escape from having to untangle what this is all about

I read recently that you said that Graham Greene’s novel The Heart of the Matter had changed your life. How old were you then? And how did it affect you?

Oh, 21, 22. I absolutely loved Graham Greene. The End of the Affair, A Burnt-Out Case – I mean, I met all those people in Uganda, this whole decay of empire enshrined in these wizened characters who still populated Africa… I don’t think Greene changed my life but he confirmed my life: he confirmed that what I had experienced was not unique. Another thing I liked about him was that he was so contorted. You know, his Catholicism and his conscience were such fun. The mess he got himself into!

In your journalistic career you have met some of the monsters of the 20th century – Idi Amin, Slobodan Milošević – and have seen some horrific things. How has that caused you to reflect on the reality of evil? It strikes me that Greene doesn’t appear to believe that human beings can be evil.

And I’m kind of with that. I’m with that. You see, I think that evil is an escape. (I think this is where the Christian faith comes to grief, too.) It’s very easy to dismiss people or things as evil or the work of the devil. People call Idi Amin a personification of evil – no! he was a blithering idiot and misguided and probably disturbed, but to say he was evil is just a way to avoid having to deal with these things. Milošević is the same. And Osama bin Laden.

These words like ‘terror’ and ‘terrorist’ are an escape from having to untangle what this is all about. For example, if we were to try to see the world through the eyes of the students who seized the US embassy in Tehran in 1979, there’s actually a great deal of logic in why they did it.

What about the people who cut the throats of their hostages in Iraq?

Do you want to excuse that as evil? You see, I think that if you call people ‘evil’ you simply say they are in a compartment that defies analysis.

That doesn’t excuse them, does it? It excuses us.

Yes. And the trouble is that unless we try to explore what it is that has informed this sort of stuff, we are never going to get to the root of it. What is the root of all evil? It’s a wonderful phrase that the church conjures. I’d like to know, and I think we should do some work on it. You know, the killing of 3,000 innocent civilians in the Twin Towers was a crime against humanity; but I don’t think it helps to say it was evil.

Somebody rang me up the other day from some Christian organisation and said they wanted to get Desmond Tutu to make a pitch to Osama bin Laden to engage in a conversation with him. They said: Was it a good idea? I said: I don’t suppose you will get Bin Laden to do it, but you go for it! Why not? Try anything!

Your editor at ITN once rebuked you for ‘not sticking to the facts’ when you described two of Amin’s men as ‘evil men with a long history of brutality behind them’. It seems to me that now the media are full of value judgements about ‘thugs’ and ‘terrorists’.

Yes, I think they are. But the agenda is very often set by the politicians, and we shouldn’t exaggerate the role of the media. It was George Bush who came up with the concept of a ‘war against terror’ and who started using the word ‘terrorist’ in a most elastic way. I think we should be more discriminating about how we use such words, but it’s very difficult when the leader of the Western world says he’s conducting a war on terror not to get sucked in.

I think that any communication between a journalist and another human being has to be holistic. You owe the viewer an emotional take on what is going on as well as a factual one

I often find post facto, even as I have emitted the words, that I have said something on air with which I disagree. Maybe I have used the word ‘terrorist’ – somebody’s written it there for me, or I have written it myself. I think we play fast and loose with language and its consequences, and I think we’re in a bad place, if you want to know. We’re in a bad place. We need to start deconstructing what we’re talking about and go back to first principles.

And maybe that’s something the church would be good at. The trouble is, the church has used all this phraseology itself all down the years and we’ve carried it on.

I was very struck by the fact that you have a good word to say about Colonel Gaddafi –

Yes, a very interesting man. Slightly bonkers.

And yet you think we turned a blind eye to Amin for far too long. Is it better to condemn a little less and understand a little more, or are we too tolerant of tyrants and ‘terrorists’?

I think we do need to understand people like Amin, but we also need to be prepared to condemn them. I think we need both. We tolerated Amin without understanding him. Actually, I think it suited us to leave people like Idi Amin behind.

I was intrigued by your encounter with John Negroponte when he was ‘effectively America’s proconsul in Central America’.2John Negroponte was US ambassador to Honduras from 1981 to 1985, and was allegedly complicit in various ways in the terror inflicted in those years on Honduras and Nicaragua. When this interview was conducted, he was US ambassador to Iraq. How does he compare with the more obvious monsters?

Life is not black-and-white, it is shades of grey, and I think you need to explore all the shades to develop a view about what you’re dealing with. You need to recognise that on our own side there are patches of acute darkness, too.

I happen to think that Churchill and Eisenhower did the world a massive disservice in overthrowing Mossadeq3The government of Dr Mohammad Mossadeq was ousted in a coup orchestrated by MI6 and the CIA two years after it nationalised Iran’s oil industry. as the democratically elected prime minister of Iran in 1953. I think it was wrong (and if we apologised, it would actually give us a good new start in Iran). What did we think we were doing? What did the Americans think they were doing when they overthrew the democratically elected president of Guatemala in 1954?4Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán was ousted by the CIA after he tried to nationalise plantations belonging to the United Fruit Company. We have no right to do these things.

Do you think that current affairs are reported without enough historical background?

Yes. I think the answer is absolutely yes: there is not enough analysis and not enough context. More than anything, I think we need to press the pause button. I don’t think there’s enough time in our society for contemplation, for thinking about the world about us and trying to unravel and analyse things for ourselves. Because we want it now: we just want whatever the information is now and that’s it.

Or that’s what the media say we want. I actually think we want much more than that.

One refrain in your book is that the things you have witnessed have made you cry. Is there a place for emotion in good journalism?

Well, human beings are emotional creatures and I think that any communication between a journalist and another human being has to be holistic. You owe the reader or the viewer – whether they would like to be there or are jolly grateful they’re not – an emotional take on what is going on as well as a factual one. If you denude an event of all emotion, you are doing your consumer a disservice.

But I don’t cry on camera…

How do you avoid becoming desensitised? Is it inevitable that you become hardened?

Almost the first image I encountered in El Salvador was 15 coffins lying in front of this Graham-Greene-like white-stucco church. It was deeply shocking, but it was also a fantastic image

Yeah. You’d pack it in if you really let it get to you, but only a certain amount does.

There is a danger that you do become inured to it if you allow this business of being a journalist to be the be-all and end-all of your life – if you have no hinterland, if you don’t play the piano or nurture your kids or cultivate cabbages or do something that gives your life another dimension. But if you live a relatively wide-ranging existence beyond your work, it informs your work constantly and renews it. For example, once I became the father of children I began to see the suffering of children through their eyes and to some extent perhaps that refreshed the emotions that had become dulled by constant exposure.

You recount how you found 780 orphaned children trapped in a warzone in El Salvador and you remark, ‘Their plight made brilliant television.’

Yeah, it did.

It struck me as a shockingly cynical comment. Was it self-consciously so?

No, I was being honest. You know, I am in a trade which involves wanting to get brilliant images that encapsulate what’s going on, and this was a brilliant image: 780 orphans living under the barrel of a gun. People have to watch, you know, and you have to have images that will ignite their interest in some way. You can’t just put boring pap on.

But were you shocked at all at your own reaction? Is there a tension between your different reflexes?

But there were so many other reactions. Elsewhere in El Salvador I cried. But if I go around weeping buckets I’m not going to be much use to the viewer. At some point I’m going to have to recognise that I’ve just seen something which will wake the viewer up. Almost the first image I encountered in El Salvador was 15 coffins lying in front of this Graham-Greene-like white-stucco church with a tolling bell (these were people who had been massacred by the death squads, you know?). It was deeply shocking, but it was also a fantastic image. Could you ask for more? Could you ask for more? Cynical bastard! How dare you say that? But I’m afraid I can.

During the Falklands Conflict, you saw the ‘pitiful sight’ of the Hipolito Bouchard limping home to Argentina with the survivors of the Belgrano huddled on her decks. When you meet politicians who have ordered acts of war but have never witnessed the consequences, how do you feel?

You know, it’s impossible when you’re looking at somebody who has authorised something like that to connect the two. It’s very, very difficult [in 2004] to look at Tony Blair or Geoff Hoon or whoever and say, ‘Ah! I have in front of me the man who –’. It just doesn’t feel like that.

You feel in the end that you are simply involved in an organic process in which everybody, even you, has a part to play. You feel that their part is bigger, but you don’t actually say, ‘There’s the murderer!’ It’s more complicated than that. I mean, there are all the interests that fuel military activity…

The instincts of someone such as John Pilger would be to want to take Blair and Hoon and confront them with, say, civilian victims of cluster bombs in Iraq.

Oh, certainly. But one of the reasons why for me Pilger fails is that he does want to structuralise it in too formal a way. We all know from experience that life doesn’t work out quite that way. I think there is much more fuck-up than conspiracy.

I don’t think the media have ever really had a profound interest in finding out what people really want. Do you think the public really wants the tabloid trash we’re fed?

You know, if the world was as black-and-white as some people would like to make it, we’d know exactly what to do. We never do. We never did with Saddam. In fact, we did create a rather clever military structure for containing him which now appears to have worked, but we were equally unclever by developing a range of sanctions that enabled him to become very rich while his people became extremely poor. If we had easy solutions to these things, if it really were good against evil, I would have thought we’d have the world fixed. But it ain’t.

As a newsreader now, you’re a mediator between two very different worlds: the front line, or whatever, and the suburban sitting room. These worlds are so far apart, I wonder whether at times you want to reach out and grab the viewer and ask them, ‘Have you any idea what this means?’

No, I don’t feel any such frustration at all, because I hope that it’s possible to make things so accessible that people can put themselves in the place of the person you’re reporting about, be it Tony Blair or a starving child in Ethiopia – or at least understand what it must be like to be them. And once they do that, it will motivate them to find out more, or even do something. And that in the end is what we want to achieve, isn’t it? That people will not only be informed but will actually act upon that information.

If you don’t find it frustrating, that means –

I think it works. I think I’m in a very privileged position, of being on a programme that has the time and commitment to explain. And I think that it works. I’m sure it works. When I meet my viewers on the street or whatever, they say things to me that indicate to me that it does work.

In practice, journalism is committed to ‘the story’ rather than the truth, isn’t it? And TV news especially is addicted to what is accessible and telegenic. Shouldn’t the news come with a warning to consumers: ‘This programme will give you a distorted picture of what has been going on in the world today’?

Consumers are not half as stupid as we make them out to be. They know it can’t be a complete picture. We do what we can do, and we do it badly in many cases. There are times when the media do a superlative job of shining a light in a very dark place and there are times when they do an absolutely ridiculous job and fail to shine a light where it needs to be shone. I mean, absolutely no question, there’s far too much time spent talking about [the model] Jordan’s breasts rather than really examining why we’re in Iraq.

But when you describe the eight-year Iran-Iraq war as ‘so unreportably big and so unchangingly active that newsdesks stopped sending’, you’re acknowledging that there are blind spots in television news.

Yeah, yeah. Yes, absolutely.

A key conclusion of the book is that we are now in a dangerous situation where, thanks to CNN and the BBC and Al-Jazeera, the South knows in ever more detail how the North lives, whereas our media keep us in ignorance of the world beyond Pop Idol, ER and EastEnders. But surely the programmers serve up what the public wants and so it’s really our fault?

You’re an optimist! The programme-makers are not really serving up what the public wants: they serve up what they think the public wants. They do these corrupt surveys – they have a pretty bent system for checking what people are actually watching, which tends to count sets on rather than whether anybody is actually watching what is on on the sets. I don’t think the media have ever really had a profound interest in finding out what people really want. People say they don’t want in-depth news and current affairs at seven o’clock, but Channel 4 News put on 15 per cent last year. Something wrong there.

I think you have to be an optimist if you’re going to endure these collisions with our frailty. Because otherwise you’d say, ‘God, I think I’ll slit my throat’

Do you think the public really wants the tabloid trash we’re fed? It’s very funny and all the rest of it, but… I mean, the internet shows that if you make available pornography, or just tittle-tattle, people will go for it, because that’s in all of us; but if you don’t, they get on and do something more creative.

Order and disorder are a key theme of the book. Some people would argue that the global order of a pax Americana is better than the uncertainty of local, regional and global struggles for dominance. Is that a view you would share?

Not entirely. Not entirely. I think the pax Americana is a very Northern settlement and I don’t think it really takes account of other ways of life, other faiths and other philosophies. For example, I think it’s fantastically misguided when we say we’re going to impose (or, rather, offer the opportunity for) American-style democracy in Iraq. I mean, Iraq is 8,000 years older than the United States. Now, that doesn’t necessarily mean that Iraq knows any better than the US, but it does suggest that there may be some elements of Iraqi culture that are worth exploring and fostering rather than going in there and plonking something which was devised by George Washington, John Adams and Abraham Lincoln.

What we’re dealing with in America is a country that has managed to subsume every culture that it has embraced. All those immigrants have gone and in a sense cast their identity and their culture into the melting pot. Now, the Americans think they’ve got the solution and maybe they have. Maybe the world is just one great big melting pot and we are all waiting simply to be like each other. Or maybe there is a greater and fiercer sense of identity which wants to preserve a sense of Islamic commitment or whatever it is. I think it would be dangerous to think that one or the other culture has yet discovered the elixir.

Is there anything in the Bible that has particularly resonated with all you have been witness to?

Yeah, I think treating your neighbour as you would have them treat you is a pretty good idea. I think that turning the other cheek is a pretty good idea. I think there’s a fair amount on conflict resolution in the Bible. But the problem with the Bible, as is well illustrated in Middle America, is that it’s very open to a pick’n’mix approach.

One biblical principle that seems to me to be implicit in your book is that we reap what we sow. What would we have to sow to get a better harvest in the world? Is the idea of overcoming evil with good a sound political principle as well as a personal one?

I don’t think that’s the key. My solution is not that good will prevail over evil but that justice will prevail over injustice. Or should.

You’ve said that you believe in change, meritocracy and progress. How do you relate to Graham Greene’s view of humankind as essentially weak? There’s not much upwards thrusting in his world…

I look to Greene in a sense for the bad news of the reality of the weakness of the human soul and I look to other places for the optimism.

And where do you see improvements coming from?

From within us. From our inventiveness, our imagination. But you need both. You need an awareness of human frailty and an awareness of the possible.

Would you describe yourself as an optimist?

Absolutely, 100 per cent, yes. Yes. And I think you have to be if you’re going to endure these collisions with our frailty. Because otherwise you’d say, ‘God, I think I’ll slit my throat.’

This edit was originally published in the Winter 2004 issue of Third Way.

To make sure you hear of future interviews in this series, follow High Profiles on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

| ⇑1 | Shooting History: a Personal Journey (HarperCollins, 2004) |

|---|---|

| ⇑2 | John Negroponte was US ambassador to Honduras from 1981 to 1985, and was allegedly complicit in various ways in the terror inflicted in those years on Honduras and Nicaragua. When this interview was conducted, he was US ambassador to Iraq. |

| ⇑3 | The government of Dr Mohammad Mossadeq was ousted in a coup orchestrated by MI6 and the CIA two years after it nationalised Iran’s oil industry. |

| ⇑4 | Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán was ousted by the CIA after he tried to nationalise plantations belonging to the United Fruit Company. |

To find out more about the agenda behind our interviews, read our manifesto. To access our archive of more than 260 interviews, see the full list.

Biography

Jon Snow was born in 1947 and educated at St Edward’s School, Oxford and Scarborough Technical College. After a year with VSO teaching English at Kamuli College in Uganda, he went to Liverpool University in 1968 to study law but was sent down in his second year for ‘bringing the university into disrepute’ as a ringleader of a sit-in in the Senate building. He never completed his degree.

In 1970, he was employed by Lord Longford as director of the New Horizon Youth Centre in the West End of London.

Three years later, he joined Britain’s first commercial radio station, LBC, reading the news and then being sent out as a reporter, to Northern Ireland, Portugal and Uganda.

In 1976, after turning down an approach from MI6, he joined ITN, reporting from East Africa, the Horn, Vatican City, Iraq (where he helped to rescue the crew of a British bulk ore carrier trapped by the war with Iran), Iran, Afghanistan and Central America.

In 1983, he was appointed as ITN’s Washington correspondent. Three years later, he began a three-year stint as its diplomatic editor.

In 1988, after presenting News at One on ITV, he joined Channel 4 News, becoming its full-time presenter the following year. He was lent back to ITV in 1992 to anchor its election-day coverage, and continued occasionally to report from overseas, including presenting Channel 4 News for a week from India in 2002 and Baghdad in 2003.

Over the years, he has reported the Falklands Conflict (from Chile), the summits between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev in Geneva, Reykjavik, Washington and Moscow, the release of Nelson Mandela and the fall of the Berlin Wall, and has interviewed, among many others, Idi Amin, Muammar Gaddafi, Pope John Paul II, Fidel Castro, Reagan, Rajiv Gandhi, Gorbachev, Mandela, Yasser Arafat, Slobodan Milošević and Monica Lewinsky.

Also for Channel 4, he has presented First Edition, a current-affairs programme for children that ran from 1994 to 2002, and Weekly Planet (from 1998 to 2000); and has made several documentary films and chaired many televised debates and discussions.

He has won numerous awards, including the 1979 Monte Carlo Television Festival’s Golden Nymph for the best news documentary (on the bombing of a children’s hospital in Eritrea) and the Valiant for Truth Media Award in 1981. The Royal Television Society named him ‘TV journalist of the year’ in 1980 (for his reports of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the failed US attempt to rescue its diplomats held hostage in Iran), ‘male presenter of the year’ in 1995 and ‘presenter of the year’ in 2003; and also honoured him in 1979 for his report of the new Pope’s return to Poland, in 1981 and 1982 for his reports from El Salvador and in 1989 for News at Ten’s coverage of the Kegworth air crash.

He was visiting professor of broadcast journalism at Nottingham Trent University from 1992 to 2001, and since then has been visiting professor of media studies at Stirling.

He has been chancellor of Oxford Brookes University since 2001. He has chaired the New Horizon Youth Centre since 1986 and also served as chair of the Prison Reform Trust from 1992 to 1997 and deputy chair of the Media Trust from 1997 to 2003. He is also a trustee of the National Gallery, the Tate (he has chaired the council of Tate Modern since 2002) and the Stephen Lawrence Trust, and a director of the Tricycle Theatre.

He has received honorary doctorates from Nottingham Trent University and the Open University, but recently turned down an OBE for his work with the homeless.

He is the author of Atlas of Today: The World Behind the News (1987) and Shooting History: a Personal Journey (2004).

He has two daughters with his long-term partner, the lawyer Madeleine Colvin.

Up-to-date as at 1 January 2005