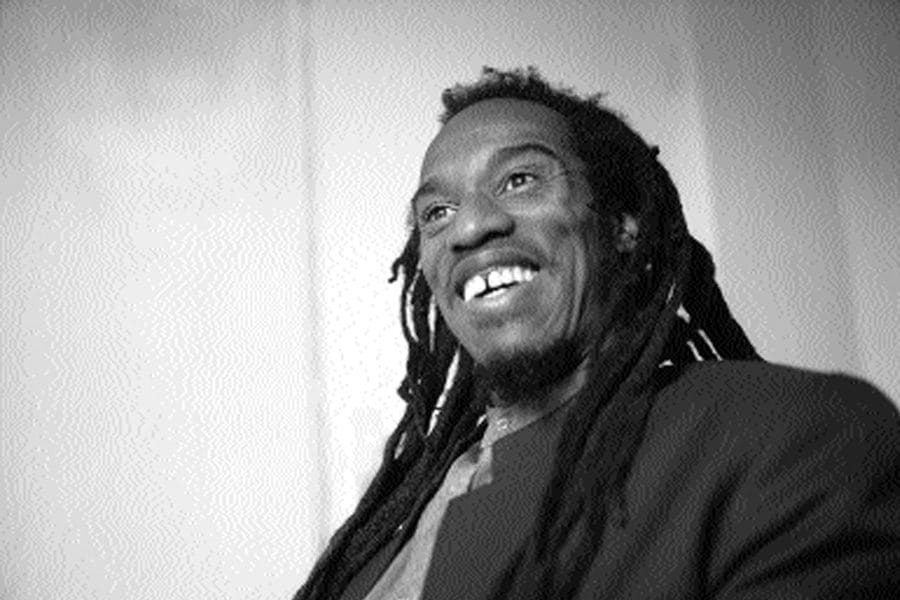

Benjamin Zephaniah

describes himself on his own website as a ‘poet, writer, lyricist, musician and naughty boy’. Simon Joseph Jones sat down with him at The Bookshop in east London on 24 May 2005.

Photography: Andrew Firth

You are the eldest of nine, but you were the only one who stayed with your mother when she left your father. How did that affect your outlook?

When you come from a broken home, or a home where there’s violence, you almost think it’s normal. So, I just thought that most families fight. I once asked a friend of mine, ‘What do you do when your dad beats your mum?’ And he went: ‘He doesn’t.’ I said, ‘Ah, you come from one of those, like, feminist houses. So, what do you do when your mum beats your dad?’

When my mum was on the run from my father, she’d go to a new house and she’d say, ‘Right, son. This is your new name.’ (My dad had a job where he could track us down really easily.) And I’d go, ‘Right, OK. I’ll go out and make some friends now and play football.’ You know? That was it. People would be calling me ‘Tom’ or whatever, but I didn’t sit down and agonise over it all the time.

I remember when I realised that it wasn’t normal, thinking that one day I want to tell people what this feels like. You see, deep down I always knew I wanted to be some kind of storyteller.

I wondered what sort of ambitions you had then.

There were two worlds. There was my mother and other people saying, ‘You’ve got to get an apprenticeship’ (and for us it was, like, painter and decorator or car mechanic or something like that). And there’s me inside going, ‘No, I’m a poet. I’m a poet. The world is my muse.’ I remember my mother sitting me down one day and saying, ‘Look, son, how do you, a black man in a racist country, expect to earn your living from poetry?’ But I always had a strong sense of what I wanted to do.

Police at the time were, like, out-and-out racists. It’s difficult for people to imagine now. A couple of policemen would pull up and say, ‘Over here, nigger!’

When you left school at the age of 13, you couldn’t read or write. How did you start creating poetry?

Well, for most of the early part of my life I thought poetry was an oral thing. We used to listen to tapes from Jamaica of Louise Bennett,1louisebennett.com/about-miss-lou who we think of as the queen of all dub poets. For me, it was two things: it was words wanting to say something and words creating rhythm. Written poetry was a very strange thing that white people did. It was only later that I met somebody who had some qualifications who said, ‘You’ve got to write that stuff down.’

When you were a teenager, you started getting into trouble with the police. How did that begin?

I think it’s partly to do with the estates we lived on, partly to do with being black and partly to do with police who at the time were, like, out-and-out racists. It’s difficult for a lot of people to imagine now – I mean, it does happen, but then it used to happen often: a couple of policemen would pull up and say, ‘Over here, nigger!’ Who’s that to? ‘You, nigger.’

There are many things, I think. When our parents arrived from Jamaica – or Barbados in my case – they were good Christians, they were grateful for this place, you know, and they thought, ‘We’ve got to behave ourselves. They’ve given us houses to live in and factories to work in and we’re just going to toe the line, because we were invited here.’

And then there were us, who went: ‘Well, we’re not quite Jamaicans. We’re probably more British than Jamaican. And actually we don’t want to stay at home all day reading the Bible, you know? We want to go out and play.’ And in them days the big thing for any teenager was the youth club, but in our area the clubs were basically white and we couldn’t go into them, or certainly not without a big fight.

We would’ve been prepared to hang out on the streets, but I soon discovered that there’s a culture in Britain that says that that’s not really done. A policeman would come up and say, ‘What are you doing here?’ You couldn’t say, ‘I’m just here’ because he’d say: ‘Where are you going?’ I always found that really strange. I mean, in the Caribbean you could just be out, but in Britain you always have to be going from one place to another, you know?

So, we have to go somewhere, so we need some money. Parents aren’t going to give us money – they ain’t got any money anyway. So, then we go stealing. Most of the time, it was petty crime.

Actually, you didn’t have to steal – that’s why I think there are many answers to your question. But I’m absolutely sure that if I hadn’t got involved in crime I still would have had a police record. I remember police officers looking at me, a black guy who hadn’t got a record, and, you know, ‘We’ll fix him. We need to know where he is. We need his data.’

How did you escape from that spiral?

I tried being a good Christian in my mother’s church, but I thought: It’s really happy-clappy and it makes me feel good for a couple of hours – but what are they doing for other people?

Well, this is a big jump forward now, because I went to an approved school and Borstal and all that stuff. I used to have a little ‘business’. Kids used to work for me – they used to steal tools out of car boots and I used to sell them on, and I had one or two other schemes going on. Constantly I had people saying to me, ‘You should do something with that poetry, you know?’ but I became a fucking car thief and a fucking pimp and this, that and the other, and my teacher said I was a born failure and told me I was going to end up dead or with a life sentence. It was just at that time when guns were becoming more accessible and it was getting to the point where to carry on doing my business I’d have to be armed. And I really didn’t want to do that.

And so I just woke up one day and said, ‘I’m going to London.’ Just like that. It wasn’t that London was a better place, it was just that I wouldn’t have been in the same circle. I would have got out of the spiral. I had money to collect and everything and I went, ‘Leave it! I’m going.’ I’m quite sure that I wouldn’t be around now if I hadn’t.

Did your mum see it as an answer to prayer?

No, even she was asking me to stay. I remember saying to her, ‘Mum, the next time you see me it’ll be on television.’ I remember saying that to her as she was [crying], ‘Goodbye, son!’

What role had religion played in your life thus far?

Well, I tried being a good Christian in my mother’s church, but I just thought: It’s really happy-clappy and it makes me feel good for a couple of hours, but it’s all about dying and going to heaven. What are they doing for other people? They’re saying they’re going to save their souls, but they’re not prepared to save them from injustice or famine and all that kind of thing. I mean, I saw some good in it, and I saw some good people in there.

And then I got very interested in Islam. There’s no happy-clappiness there, but, well, ‘Islam’ means ‘submission’ and you have to give up lots of things, and I just wasn’t prepared to give them up. By that time, I’d started to think a lot about women in particular. Islam is stereotyped as a religion that’s bad to women and it’s not all bad – I know lots of women that take to Islam willingly – but personally I didn’t like it. To be honest, I didn’t like a lot of its rules for men, either. But certainly I didn’t see equality.

You then began to gravitate towards Rastafarianism.

I was attracted to Rastafarianism because it allows you to be political and spiritual at the same time. But even then I realised that within the Rastafarian movement there were many hypocrites. I remember some Rastafarians came over from Jamaica and one night we were at this gathering and they really impressed me with their teachings, and then at the end of the gathering I saw them literally kidnapping a girl and putting her in the car and taking her away.

But I always felt there’s something greater than us. I hesitate to use the word ‘God’, because when we say ‘God’ we think of a male and we think of a bloke up there. I think there’s some kind of spiritual power, some ‘nuclear’ power that’s greater than us.

I think I’m probably angrier now than I was before. Before, I thought we were being ripped off; but now I know how bad it is, you know?

And then I went on a couple of long trips to holy places around the world, just to see, you know? If I went to the place where Jesus was supposed to have been born, would I connect with it? And I thought: ‘They’re all tourist traps.’ I remember going around Jerusalem with a guide and he was saying: ‘This is where Jesus did this and this is where Jesus did that. This is where Jesus went to the toilet.’ And I said to him, ‘Do you believe this?’ And he went: ‘No, I’m a Muslim, stupid. This is my job, man.’

You have said elsewhere that you lost your religion but found your faith. What does that mean?

I think religion has given God a bad name. When I say ‘faith’, I’m talking about a belief, for want of a better word – I think I have a better word: a knowledge of God – that I get through meditation, which doesn’t need anybody else: doesn’t need the church, doesn’t need a priest, doesn’t need an imam, doesn’t need anything. Just learn to meditate!

My religious hero, if you like, is Bodhidharma, the guy that founded Zen Buddhism and the kind of patriarch of kung fu, who converted loads of China, Japan, all these places, to Zen Buddhism. He didn’t preach a ceremony, he didn’t have a book, no Bible or anything like that, he didn’t have any disciples. When they came to him and said, ‘How do I get enlightenment?’ he just said, ‘Listen to yourself!’ The most he would give you was breathing exercises and that’s it. He’s my hero because he got so many people into – he wouldn’t even say ‘believing in God’, but getting in touch with themselves.

It’s the old thing: Jesus probably wouldn’t have been a Christian, you know? Marx wouldn’t have been a Marxist. Bodhidharma wouldn’t have been a Buddhist. If you asked him, ‘How do I become a good Buddhist?’, if you were a Christian he’d say, ‘Go and be a good Christian!’ Find your own way! But the important thing is to listen to yourself. And that kind of fascinates me. What I learnt from travelling to all those places is that people are looking to the sky and saying, ‘How did we get here? Why are we here?’ and they’ve lost the ability to sit down with themselves and meditate.

I think of meditation as something that lowers the temperature, but when I think of your poetry there’s a lot of rage in it. How do those two things marry?

Yin and yang. It really is not so strange. If you think about the Zen Buddhists in martial arts, for example – very peaceful people but they can beat you up in two seconds.

You’re interested in martial arts as well, aren’t you?

Yeah. It really is yin and yang. I mean, every day I have to find some time for meditation. I’ve just got to sit silently, even if it’s just for five minutes. And it’s amazing what it does. You cut off from everything else and because you have to sit with a straight back and your legs crossed, for example, you’ve got to think about that, and then your eyes are focused and then you’ve got to count your breaths.

Every now and again the Establishment thinks, ‘Let’s give him an OBE or something!’ They try to appropriate me – and then they go, ‘Fuck! He’s still militant!’

I am very angry about many things, and back in the days when I didn’t know how to meditate I’d lose my temper and end up in a police station. Now I don’t end up in police stations so much, but I’m just the same – actually, I think I’m probably angrier now than I was before, because I know more. I mean, before, I thought we were being ripped off as citizens – well, not as citizens in our case but as subjects and consumers – and I had some idea about how we were ripped off; but now I know how bad it is, you know? And they’re still getting away with it…

On top of that, I’m one of the generation that was promised that after the fall of the Berlin Wall we were going to have peace and all this stuff, and with the coming of the internet we were going to have such great communication we were all going to be, like, close to each other and there were going to be fewer wars. You know? And it was a load of bullshit. So, I’m more angrier now, and I think that comes out in my poetry.

One thing my mother will say is that when I’m on stage, that’s me. She sees me doing this interview, she’ll go, ‘He’s nervous and he’s trying to find the right words’ and stuff like this; but when I’m on stage doing my poetry, that’s me. I can go from one extreme to the other, even on stage. At one moment I can be really angry and the next minute it gets really funny.

My favourite poem of yours is ‘Christmas Has Been Shot’. It’s got those great lines:

And yes it was written that the truth shall flow

From the mouths of babe and suckling,

But babes and sucklings beware

The soldiers have orders to kill,

And the spirit of King Herod is alive.

But if you read that in church at Christmas, you get the impression that people want to hear ‘Be nice to yu turkeys dis Christmas!’ instead. You have two different personas: one furious, one family-friendly.

In the early Eighties it was all very angry stuff, but, you know, there was a lot of angry poets around and they all burnt out and they’re not here any more.

I do love having fun with poetry and I think that what happened is that I became (I sound like I’m blowing my own trumpet here) so popular that the BBC and others had to use me in some way and the best way was to pick up on my children’s poetry. I mean, ‘Talking Turkeys!’ was voted the fifth-best children’s poem of all time…2See bit.ly/2zP7Fdl.

So, every now and again the Establishment thinks, ‘Come on, he’s really softened up. Let’s give him an OBE or something! Let’s give him a post at a university!’ They try to appropriate me – and then they go, ‘Fuck! He’s still militant!’ You know?

I do really believe that good will triumph over evil. Not that I’m good, but I can inspire some good people

I can’t understand why you were ever offered an OBE when you have said in so many words that black people who accept honours are Uncle Toms. Wouldn’t they say, though, that it’s more productive to compromise and get in with the Establishment than to remain on the outside, sounding off?

Well, when the Queen is pinning an OBE on you, you can’t whisper in her ear, ‘Can I have your phone number? I want to talk to you about a few deaths in custody.’ You’re not really on their side. But for their purposes… It’s a bit like the artists who broke the boycott of South Africa. The Establishment can say, ‘Look, we can’t be that bad: Benjamin Zephaniah is a Member of the British Empire.’ You know?

I’m not thinking just about honours. Haven’t you said that nobody black would grieve if any of our current black politicians disappeared?

Because they don’t do anything for the community. Look at how black people felt about the war in Iraq and still feel about it. What black politician has got up and said anything? They all want to be the first black prime minister. What politician do you hear going on about how many black people are dying in custody? Someone said to me the other day, ‘Why should black politicians in particular be outraged? White people should be outraged by it.’ And I said, ‘Yes, that’s true, but the thing is, the black politicians came to our communities and made us promises that if they were voted in they would take care of it. That’s the difference.’

How hopeful are you of achieving your goals, as an activist or an artist? Are you an optimist?

I think I have to be, you know? If I really felt it wasn’t worth it, I think I could easily do something else and earn more money. Lately I’ve been doing nude modelling and I could do some more of that, for example. I could write cartoons (which I would enjoy doing). I could make records that are not political and are just pure dance music. But I do really believe that good will triumph over evil. Not that I’m good, but I can inspire some good people.

And I don’t know who it was who said it, but I do believe that capitalism will eat itself. I think we are going to have to build societies that are not rooted in money and wheeling and dealing. It’s going to happen. You know, money only works because we all believe in it.

Why do you think I should break the law every day?

For me, it’s a kind of token gesture. You see, I own my own house, yeah? I own my cars – I don’t have to steal them. Yeah? I’m not rich but I’ve got money to live on. And I was beginning to get worried. I thought, ‘Fuck it, I’m becoming really, really safe. I don’t smoke. I can’t get done drinking-and-driving – I don’t drink.’ And so I just felt: How can I break the law every day? Just do something! Pull out your willy at a bus stop! If you’ve got a car, speed! If you’ve got a bike, ride on the pavement! Anything. Just do something illegal at least once a day and be proud of it! I don’t think you should allow the Establishment (if you like) to think that they’ve got you under control.

I want to know when this golden era of British fair play was. I mean, even after empire and everything, when we got left with cricket, they didn’t even play fair at cricket

Actually, it’s wrong to talk as if there’s something called ‘the Establishment’. The Establishment is just a lot of individuals. I do a lot of work for the British Council and a lot of people there are just as rebellious as me. They think: If we didn’t work here, everyone in Africa would probably think that British culture is still ballet and opera. What we do now is take out reggae and hip hop, you know?

How can you do work for the British Council and tell the world how great this country is when you are so critical of it?

Well, some people do say, ‘Why do you criticise it so much?’ If you listen to me on a British Council gig, 70 per cent of the time I’m being critical. People do ask: ‘Why did they send you? All you did is slag Britain off.’ I’ve been to some countries where I’ve walked offstage and they’ve gone, ‘Run for it!’ Why? ‘You’ve just said all those bad things. Aren’t they going to come and get you?’ They know that if they said that on stage, they’d be taken away.

You could say it promotes ideas of free speech – but then I’ll be in Nigeria or somewhere and I’ll say, ‘You know, we only have free speech to a certain extent. I wrote a poem called “Christmas Has Been Shot”; no one wants to televise that, you know? But they want my turkey poems.’

In the United States not so long ago, I was going to talk about Refugee Boy3Published by Bloomsbury in 2001 on television and this guy came up to me as I was miking up and he said, ‘We would appreciate it if you try not to talk about the Palestinians, and if you do, will you not use the term “Occupied Territories”?’ And he kept going on about it. I said, ‘Are you telling me what to say?’ He said, ‘Yeah.’ So I took the mike off and went home. This is the home of the fucking free, you know, and they are telling me what to say.

Do you think we use words like ‘freedom’ too glibly?

I think that a lot of the phrases we use… Like ‘the sense of British fair play’. Slavery? Colonialism? I want to know when this golden era of British fair play was. This justice, and all this stuff. I mean, even after empire and everything, when we got left with cricket, they didn’t even play fair at cricket.

Yeah, of course the kind of trial you can get in a British court is different from the kind you would have got in an Iraqi court, but, you know, the chances of me being stopped by the police in Iraq because I’m black… It wouldn’t happen. Because I’m a Shia, maybe… But who’s fair? You know? It’s our fairness. It’s what suits us.

It wasn’t so long ago in the East End of London, for example, that if you were a girl on the streets after a certain time you risked being taken away and forced into prostitution. If you were a kid, you risked being sent into a sweatshop or up chimneys. Over hundreds of years we’ve evolved this so-called democracy that we have now. It took us a long time and it’s not perfect – it doesn’t minister to everyone and all that stuff. And yet we can look at African countries that we have had a hand in underdeveloping and expect them to do it overnight. I find that absolutely amazing. And sometimes we give them deadlines and say, ‘If you don’t do this by then, your aid is going to be stopped’ or whatever.

I [was] doing some programmes with [Noam] Chomsky for the [BBC] World Service and he said, ‘When we look at these brutal [African] dictators and the way they treat their subjects, they are only doing what they learnt from the British.’ It’s kind of like father, like son. And most of them were educated in Britain anyway.

I know it’s idealistic, but I just want to walk down the street and just not be aware of being black, you know?

You have said that you wished your identity had never been formed by race but it had to be because of the way people reacted to you. Isn’t racial consciousness one of the first steps in fighting discrimination?

Yes, but I still think it’s a shame that it has to be. I know it’s idealistic, but I just want to walk down the street and just not be aware of being black, you know? I don’t know, do you walk down the street and think, ‘I’m white. There’s a policeman there – I’m really worried because I’m white’? Or ‘Is that person not sitting next to me on the Tube because I’m white?’

When I see an Orthodox Jew in the street, I wonder: ‘Do you want me to notice that you’re different? Is that why you’re dressed that way? Or do you want me not to notice? Or do you want me to notice that you’re different and not care?’ One could ask the same question about dreadlocks.

I suppose with dreadlocks we are making a kind of statement: ‘Hey, we’ve got the most natural hairstyle you can get and we don’t mind you looking.’

Every time I see Orthodox Jews, I think: ‘You’re a victim of fashion. The clothes that you’re wearing have nothing to do with Judaism. They’re from the ghettoes of Poland.’

But we’re always all going to be different, aren’t we?

We’re always going to be different. But I think the difference with white racism is that it’s about saying, ‘We are superior racially, and because we are superior racially it means we are superior intellectually.’ You know, within the black community – you know, Jamaicans, Barbadians – they have these ins and outs, and the Muslims and the Hindus and the Sikhs and all this; but none of them say, ‘We have the right to rule the world, on the basis of race.’ And I think that’s the difference.

I met a biologist the other day and he said, ‘It’s really strange how people could come to that conclusion, because if you look at the blueprint for a human being, it’s basically the black man.’

A longer version of this interview was originally published in the Summer 2005 issue of Third Way.

To make sure you hear of future interviews in this series, follow High Profiles on Facebook or Twitter or join our mailing list.

| ⇑1 | louisebennett.com/about-miss-lou |

|---|---|

| ⇑2 | See bit.ly/2zP7Fdl. |

| ⇑3 | Published by Bloomsbury in 2001 |

To find out more about the agenda behind our interviews, read our manifesto. To access our archive of more than 260 interviews, see the full list.

Biography

Benjamin Zephaniah was born in 1958. He spent some of his childhood in Black River, Jamaica but grew up in the Handsworth district of Birmingham. At the age of 14 he was sent to Boreatton Park Approved School for burglary, and then to Glen-Parva Borstal for affray.

He moved to London in 1979 and became involved in a workers’ co-operative, which published his first collection of poetry, Pen Rhythm, in 1980. This was followed by The Dread Affair (1985), Inna Liverpool (1988), Rasta Time in Palestine (1990), City Psalms (1992), Propa Propaganda (1996) and Too Black, Too Strong (2001), as well as six collections for children: Talking Turkeys (1994), Funky Chickens (1996), School’s Out (1997), Wicked World! and A Little Book of Vegan Poems (both 2000) and We Are Britain! (2002).

He has written three novels for teenagers: Face (1999), which was shortlisted for the 2000 Children’s Book Award and adapted for BBC Radio 4, Refugee Boy (2001), which won a Portsmouth Book Award in 2002, and Gangsta Rap (2004).

He also co-edited with Marie Mulvey Roberts Out of the Night: Writings from death row (1994) and edited The Bloomsbury Book of Love Poems (1999), and contributed to Chambers Primary Rhyming Dictionary (2004).

He was writer-in-residence at the Africa Arts Collective in Liverpool in 1988–89.

He has also made numerous recordings, including the albums Rasta (1981), Us an Dem (1990), Back to Roots (1995), Belly of de Beast (1996), Heading for the Door (2000), with Back to Base, and Naked (2005). He was the first person to record with the Wailers after the death of Bob Marley, in a musical tribute to Nelson Mandela which led eventually to the latter inviting him to host his ‘Two Nations’ concert at the Royal Albert Hall in London in 1996. He has also worked with Bomb the Bass and Sinéad O’Connor.

He has given readings all over the world, from Argentina to Zimbabwe, and he also periodically takes the Benjamin Zephaniah Band on the road.

He has written several plays for the stage and for broadcast, including Playing the Right Tune (1985), Job Rocking and Delirium (both 1987), Streetwise and Our Teacher’s Gone Crazy (both 1990) and The Trial of Mickey Tekka (1991). Also in 1991, he acted in his first television play, Dread Poets Society, which was screened on BBC2. Hurricane Dub won a BBC Young Playwrights Festival award in 1988, and Listen to Your Parents, first heard on BBC Radio 4 in 2000 (and performed at the Nottingham Playhouse two years later), won a Commission for Racial Equality ‘Race in the Media’ award in 2001.

He has written or presented a number of programmes on Radio 4 and on BBC TV, ITV and Channel 4, and often appears on the media as a performer and cultural commentator.

In 1998, he was asked to contribute to a government task force dealing with creativity in the National Curriculum.

He is actively involved in the Hackney Empire Theatre, Umoja Housing Co-op, the Irie Dance Company, Viva! (Vegetarians International Voice for Animals), Newham Young People’s Theatre Scheme, the Chinese Women’s Refuge Group, Sari (Soccer against Racism in Ireland) and Shop (Self-Help Organisation for ex-Prisoners), and sponsors the Central Park Girls’ Football Team.

In 1989, he was nominated for the post of Oxford Professor of Poetry and 10 years later was discussed as a possible Poet Laureate. He has received honorary doctorates from the Open University, Oxford Brookes University, University College Northampton and the Universities of Central England, East London, Leicester, North London, the South Bank, Staffordshire and West England. He declined to be made an OBE in 2003 – as it happened, two months after his cousin, Michael Powell, died in police custody.

Up-to-date as at 1 June 2005